A studio executive describes director Hal Ashby in Easy Riders Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And Rock ‘N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood, Peter Biskind’s indispensible book about the upstart young directors who transformed the movie industry in the 1970’s. “Ashby was the most American of those directors and was the most unique talent. He was a victim of Hollywood, the great Hollywood tragic story.”

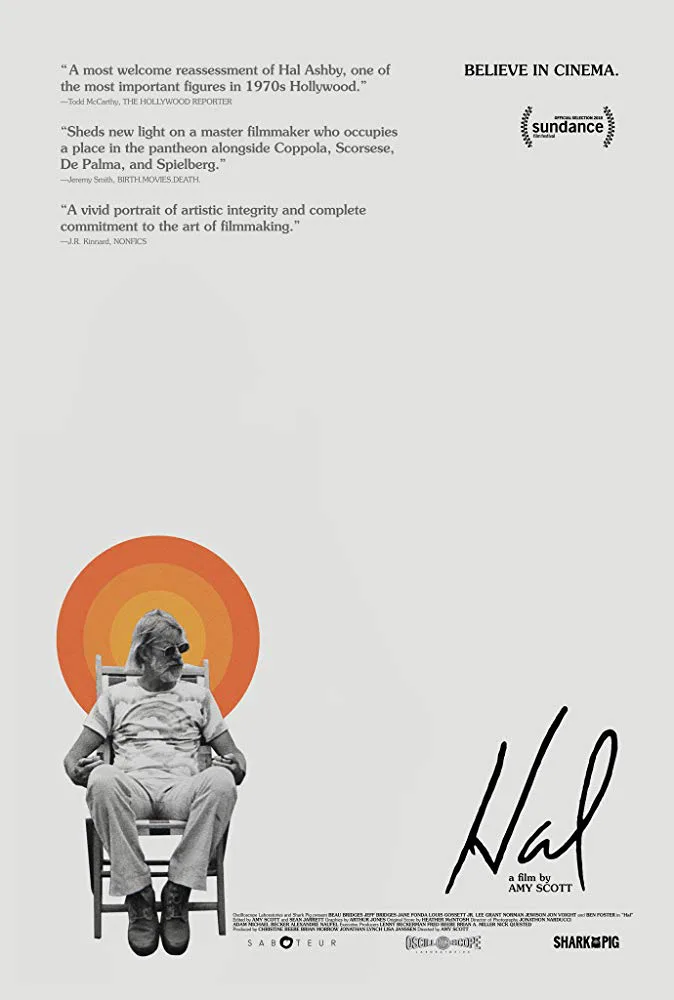

This documentary, written and directed by Amy Scott, is an appreciation of Ashby’s career, from Oscar-winning editor on “In the Heat of the Night” to director of seven classic, era-defining films in the 1970’s including “Shampoo,” “Being There,” and “Coming Home.” And it is the story of Ashby himself, with some parallels to the characters he was drawn to, people who were trying to find a place in the world where they could be honest, independent and creative and who were too often confronted with obstacles imposed by The Man.

The letters Ashby wrote as a young man to Norman Jewison, his close friend and colleague, are read with sensitivity by Ben Foster. From the beginning, he was a self-described “very, very angry young punk,” not just resistant to authority, but outraged and enraged by it. The “Easy Riders and Raging Bulls” filmmakers of the era, like their contemporaries in other fields following the upheavals of the 1960s, believed that overthrowing authority was not just their right; it was a moral imperative. As long as that was good business, some of them got away with it. They thought they were grabbing power; they did not realize that power was only being loaned to them as long as the movies they made sold tickets.

There had to be a collision. Ashby was a fierce independent who despised studio executives’ concerns about money. Choosing an expensive, collaborative medium for telling his stories was not going to result in the kind of third act happy ending studio executives were always pushing for in his movies.

The resistance to authority and being part of an organization was personal as well as political. Ashby was 12 when his father killed himself. His conflicted feelings about abandonment – both leaving and being left – led to personal and professional attachments that were intense but not long lasting, including five marriages. His real marriage was to movies. He would literally live in the editing bay, working days at a time on only two hours of sleep a night, surrounded by strips of film hanging from clothespins.

Ashby was not a movie-mad kid, like Spielberg or Scorsese. He left Utah to move to California, where he went to the state employment office to find a job. They sent him to a studio, where he ran a copier. And then he began working as an editor on Jewison’s movies. He almost forgot to show up to the Oscar ceremony the night he won. His acceptance speech was a call for “peace and love.” Biskind describes him as a 38-year-old “quintessential flower child,” with long, shaggy hair and a beard.

Ashby wanted to make movies about race, class and the Vietnam War. Instead of the brightly polished studio product, he wanted soft, dusty light and halting, authentic-sounding dialog. He put Jon Voight on a hospital gurney with a group of disabled veterans playing pool and just had him listen to them talk in “Coming Home,” and then he let Voight improvise his speech to the high school kids at the end of the film. Cat Stevens talks about how unhappy he was when Ashby used the rough demos of his songs for the soundtrack of “Harold and Maude” instead of waiting for finished versions, but admits that it was probably better that way.

Scott also shows us how Ashby worked through some of the issues of his own life in his films. She intercuts a scene from “Bound for Glory,” with Melinda Dillon telling David Carradine he needs to spend more time with the family with a surprising first appearance, two-thirds of the way into the film, of the daughter he left behind in Utah when he was a teenager and rarely saw again. The movie is frank about Ashby’s mental health deterioration and substance abuse, but the personal life sections are understandably overshadowed by the material about making the films, which itself is overshadowed by the clips of the films themselves.

It must have been daunting to make a film about a master editor and filmmaker, but Scott has clearly learned from her careful attention to Ashby’s films. The documentary is exceptionally well paced and structured, and has insightful interviews with Jewison, Cat Stevens, Beau and Jeff Bridges, and others who worked with Ashby and with today’s filmmakers who were inspired by him, Alexander Payne, Judd Apatow, Adam McKay, and David O. Russell.

Biskind wrote: “There is no worse career move in Hollywood than dying. Hal Ashby is now largely forgotten because he had the misfortune to die at the end of the ‘80s, but he had the most remarkable run of any ‘70s director.” It wasn’t dying that was the bad career movie; it was dying before older films were readily available.

The greatest tribute to this tribute to Ashby is that this movie will add “Shampoo,” “Coming Home,” “Harold and Maude,” “The Last Detail,” “Being There,” and his other films to at lot of watch lists and Netflix queues.