The question mark in the title “Hail Satan?” hints at a failure of nerve that Penny Lane’s documentary rarely suffers from. This light-footed movie is essentially a defense brief, on behalf of a group whose existence amounts to an ongoing prank-with-a-purpose, in the spirit of the Yippies, Billionaires for Bush and The Yes Men. One key difference, though, is that this group uses a combination of legal acumen and absurdist reasoning to attack its targets, and succeeds more often than you might think.

Lane focuses on members of The Satanic Temple, which was founded in 2013 and bears no relationship to Anton LaVey’s 1960s-founded Church of Satan, except for the worshiping Satan part. Ostensibly this is an organized group of Satan worshipers, the kind that made parents throw out their kids’ Dungeons & Dragons games and play records backwards in the 1980s to expose hidden messages.

But we quickly see that any religious component of their existence is outweighed by an ideological mission. They’re mainly about keeping church and state separate. That’s not easy in a country where the boundaries have been porous for centuries, and where the Evangelical right wing, which rose up in the 1950s in response to the Cold War specter of Communism, has managed to insert religion into public life to an extent that the Founding Fathers could never have imagined. (Among the many didja-know facts that Lane includes here: “In God We Trust” didn’t appear on any US currency besides the two-cent piece until 1957, when Congress added it to all paper currency. And those identical Ten Commandments statues that dot public buildings around the U.S. were giveaways from Paramount Pictures, promoting Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 film.)

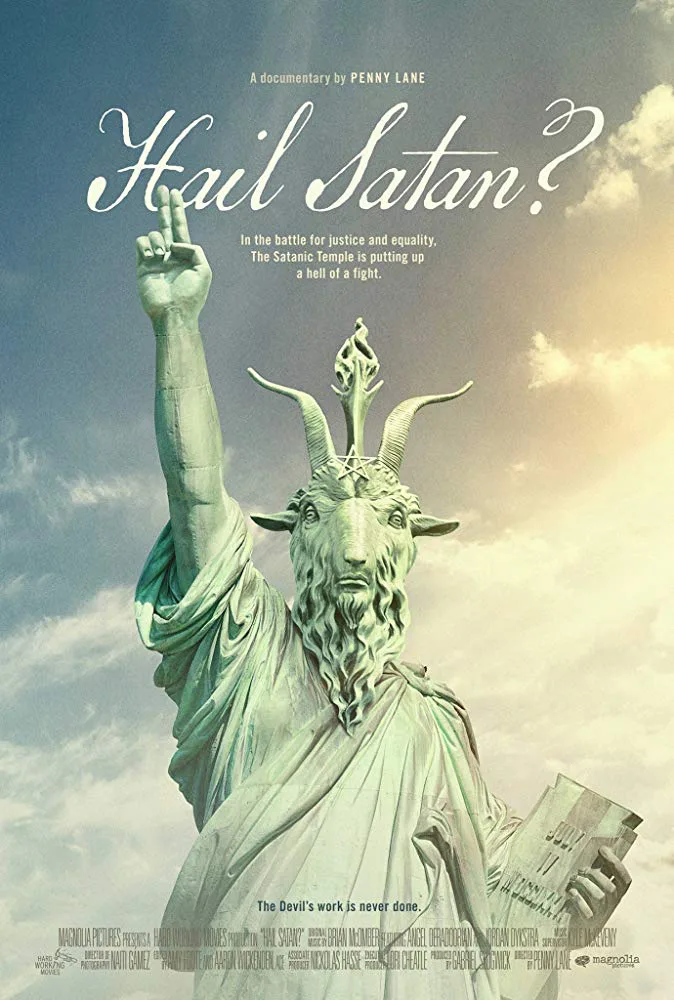

The Satanic Temple is best known for inserting themselves wherever Christian groups are trying to use public funds to praise Christianity, or integrate religious text or iconography into public commons. Wielding the first ten words of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution—”Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”—the group seeks out situations where, say, the American History and Heritage Foundation wants to put up a Ten Commandments monument on the grounds of the Arkansas State Capitol, and demands that they also put up a statue of the demon-goat Baphomet.

Throughout, Satan is treated more as a rhetorical device than a dark deity with a life force that can be tapped through incarnations or magic, as in a horror film. Devil worship is a way for Temple members to troll the dominant culture, expose mechanisms of control, and ask the sorts of questions a child might pose in Sunday school, such as “Why was it wrong for the Devil to offer Jesus food and water when he was suffering in the desert?” and “Why was it bad for the snake to offer Eve the chance to eat from the tree of knowledge, and go to live in the wider world with her mate?”

Lane directed “Our Nixon,” which viewed the disgraced president through the eyes of the people surrounding him, and “Nuts!”, a biography of a man who claimed to be able to cure impotence by replacing the testicles of non-performing men with goat testicles. She’s got an unerring eye for quirky subjects who offer an alternative perspective on American mythology, and it serves her well here, even though the unruly complexity of the subject seems to overwhelm her in the end.

The closest thing to a main character is TST spokesman Lucien Greaves. He’s a pale, smirking antihero with one glass eye—the sort of person that a horror movie might present as the smooth public face of a band of devil worshipers—but it’s obvious that the loves putting people on, and throwing shade so subtly that targets can’t be sure if they’ve been attacked or are just being paranoid. His power derives from his ability to keep a straight face whether he’s dealing with a reporter who pretends not to get the joke, or an outraged evangelical who doesn’t know there is one.

There are many other comparably dynamic characters in the film, including Jex Blackmore, the leader of TST’s Detroit chapter who plays the role of youthful extremist firebrand to Greaves’ wise but maybe too-cautious elder. Greaves himself admits late in the film that The Satanic Temple has grown so large (with chapters as far away as Australia and South Africa) that it had to have a centralized authority, a scenario he’d always hoped to avoid by organizing it in a more anarchistic fashion. One of the things that a big group has to worry about is guiding and controlling the local chapters. The latter understandably want to have the freedom to maneuver and take chances. But they’re constantly being chastised for going off-script and exposing the group to charges that they’re contradicting themselves, or alienating potential converts who are receptive to the message but not the tactics.

The philosophical conflict between Blackmore and Greaves is as fascinating as any of the details about the group and its public actions. Buried somewhere in this smart but somewhat disorganized and repetitious movie about The Satanic Temple is a trickier, potentially deeper and more all-encompassing work, about what happens to every seemingly dangerous group once it becomes popular. A small group that becomes a big group has to begin worrying about the long term ramifications of every action and statement, because it has so much more to lose than when it was a scrappy little band of figurative or literal hell-raisers. Unfortunately, Lane doesn’t really start to dig that movie out of “Hail Satan?” until the end, and she doesn’t excavate all of it—just the horns and head.

We do get a good sense of what TST is actually up to, though. It comes across less as an unconventional/threatening theological organization than a social justice group with a secular, leftist worldview that is, in its ass-backwards way, rather earnest. The Satanic Temple of Western Florida collected socks for the homeless. The Satanic Temple of Arizona organized “Menstruate with Satan,” to provide menstruation products to schoolgirls who couldn’t afford them. The group’s first public act was a rally in support of Florida governor Rick Scott, who was pushing legislation that would have allowed students to vote on whether to include prayers in public events such as graduation ceremonies. Scott, the group proclaimed in a press release, “has reaffirmed our American freedom to practice our faith openly, allowing our Satanic children the freedom to pray in school.”

It’s as if the group had studied the“Rabbit season! Duck season!” exchange from the Bugs Bunny-Daffy Duck classic “Rabbit Seasoning,” and figured out how to turn the punchline into a political movement. The larger point seems inescapable: the modern mechanisms of American government have been so corrupted by greed and organized religion that compassion and fairness are now treated as the devil’s work.