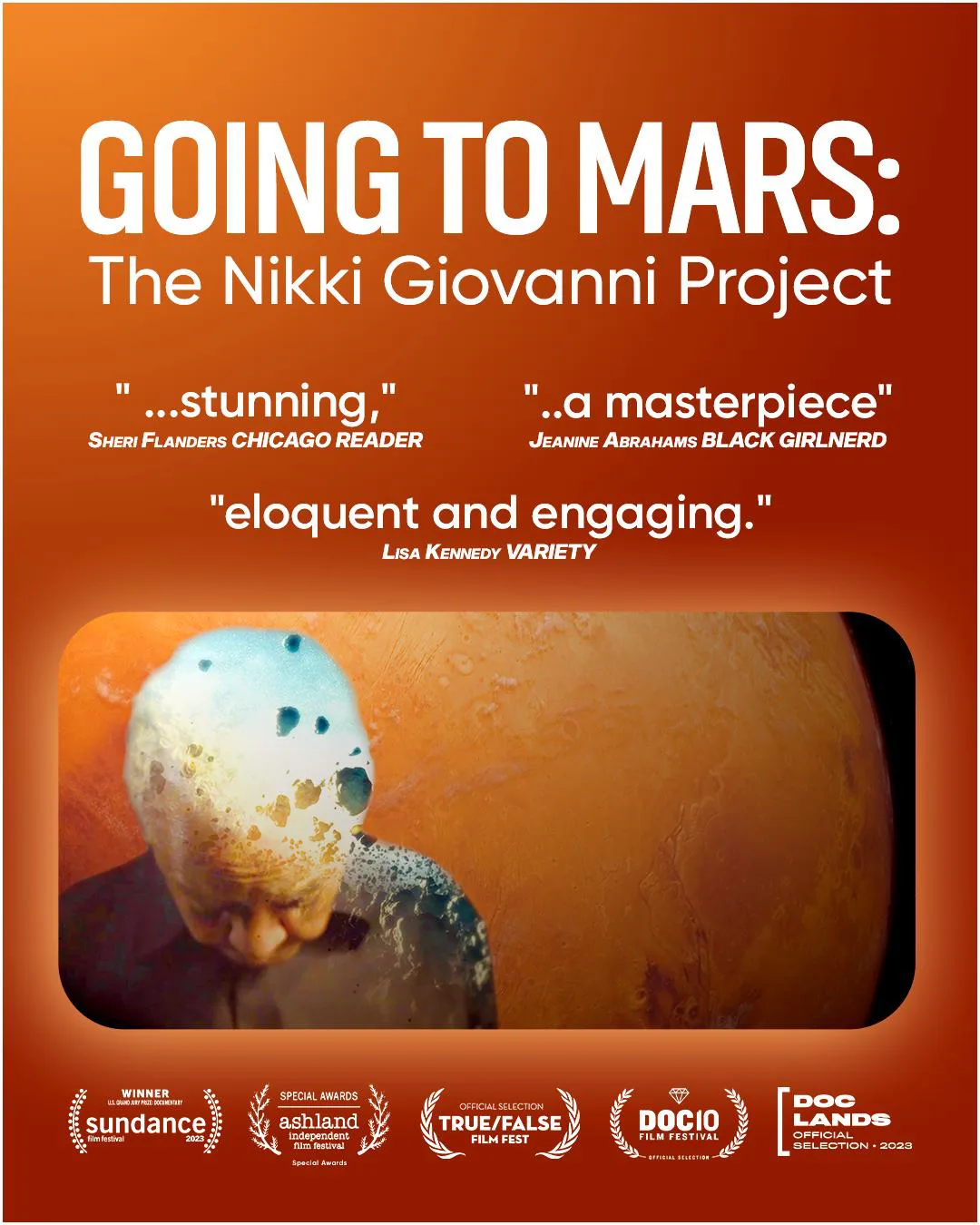

“Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project” is a feel-good artists’ profile doc that honors its subject, the American poet Nikki Giovanni, on her own terms. That’s no small feat given that Giovanni and her achievements might have easily been limited to her identity as a queer black artist, born and educated in the American South. Thankfully, co-directors Joe Brewster and Michele Stephenson successfully portray Giovanni as an exemplary and, at times, unclassifiable survivor.

Brewster and Stephenson carefully synthesize a combination of new and archival footage of Giovanni, discussing and sometimes embodying her work in her typically direct, unsentimental, and deeply moving style. Brewster and Stephenson not only have a clear picture of their version of Giovanni but also frequently remind viewers of how much more complicated and inspiring she is for resisting trite and by-now outmoded characterizations.

It’s genuinely refreshing to see Giovanni celebrated for having a personality that extends beyond faux-universal plaudits. Yes, she’s rightfully shown speaking to and lighting up auditoriums full of fans, many of whom are Black women, but not just because they presumably share similar experiences or skin color. Rather, Brewster and Stephenson keenly show and contextualize scenes of Giovanni’s public appearances, some televised and others filmed at recent speaking engagements, as proof of her animating presence. It’s one thing to hail Giovanni as an iconic presence and another to show her talk about and exemplify the qualities that have made her and her work so indispensable.

The documentary’s title hints at the focus on Giovanni as an iconoclast who skillfully avoided easy classification. This seems crucial when it comes to praising Giovanni, given how she’s written and talked about refusing to be treated as a victim despite having witnessed her father repeatedly abuse her mother.

We see Giovanni, in a 1971 interview TV interview with British TV host Ellis B. Haizlip, talking a little about her reluctance to be part of the “cycle” of domestic abuse, which she sees as part of a greater societal mistreatment of black men in America. She talks further about related concerns in one or two of a few excerpts from another televised conversation from 1971, still on Haizlip’s pioneering “Soul!” program, but this time in an interview with James Baldwin. In her considerate, sometimes qualified answers—“I chose not to grieve”—you see Giovanni’s commanding personality, the kind that can’t be reduced to general and too faint praise.

In “Going to Mars,” Brewster and Stephenson lovingly and observantly connect the modern-day Giovanni, the one they were able to film, with Giovanni in her youth. Giovanni is consistently thoughtful and warm when speaking to different kinds of public audiences, from the Apollo to a small church congregation. Throughout the movie, we see Giovanni as a rare public figure who has and continues to refuse to simply confirm her audience’s tastes.

Some of Giovanni’s poems and writing are dramatized through voiceover narration by Taraji P. Henson. Giovanni’s recitation of her work is also featured at key moments throughout, which can sometimes give them an extra emotional kick. It’s one thing to hear Giovanni talk about why she’s convinced African-American women are destined to be space exploration pioneers, and another thing to see and hear Giovanni recite some Afrofuturist poems to a rapt audience, as in a climactic scene shot at the 2016 edition of the Brooklyn-based AfroPunk musical festival. Filmed in beatific close-ups, sometimes in slow-motion, the audience seems to look at Giovanni like she’s a rock star. Brewster and Stephenson make a convincing case.

It can be difficult to both rhapsodize and profile an artist whose work explores seemingly contradictory but intrinsically related emotions stemming from their personal experiences. That challenge might be baked into much non-fiction filmmaking, but Brewster and Stephenson meet it even when they consider a potentially contentious moment in Giovanni’s public life.

In 1984, Giovanni was accused of undermining American Civil Rights leaders’ efforts to protest apartheid in South Africa. Rather than wasting more time than is strictly necessary on explaining why Giovanni was stupidly vilified for not supporting a boycott of South Africa, the filmmakers highlight the language used in American media coverage of this telling non-troversy. One article begins with a representative three-word sentence: “Poor Nikki Giovanni.” Brewster and Stephenson’s movie effectively confirms that Giovanni is anything but pitiable.

There’s nothing that Brewster and Stephenson do in “Going to Mars” that is radically different than what other docu-portraitists attempt when they pay homage to their favorite artists. Still, it’s not easy to honor the complexities of an artist’s personality while highlighting the breadth of their life and career. The makers of “Going to Mars” do right by Giovanni by showing how she speaks for herself.

Now playing in theaters.