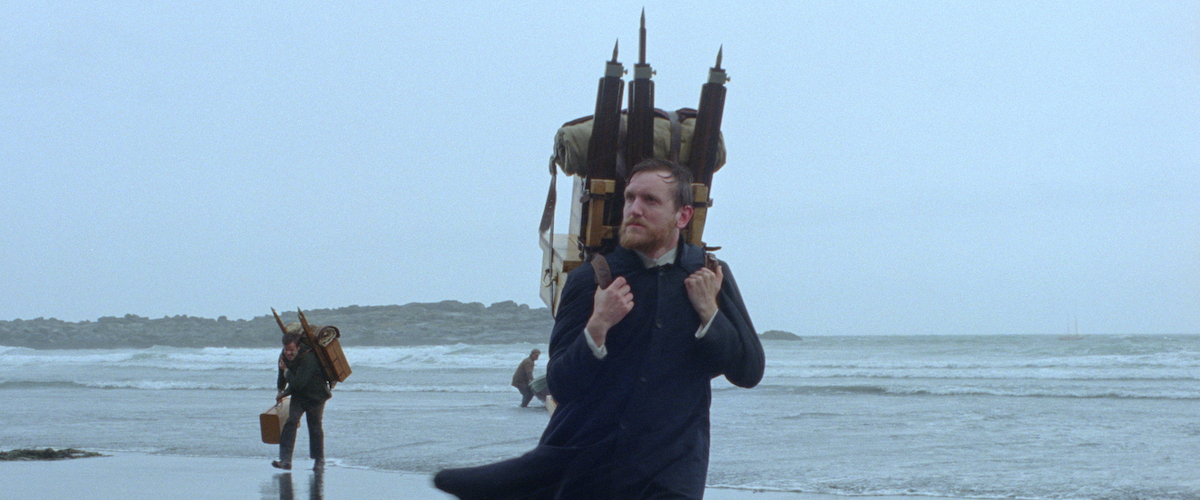

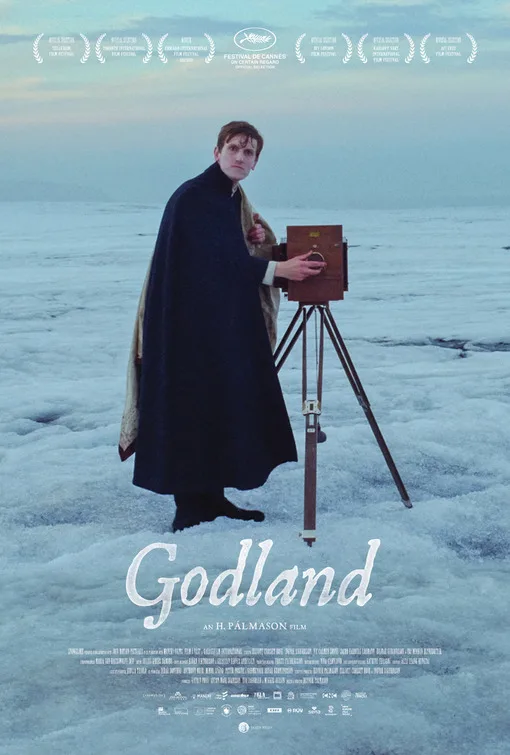

On its face, the uneven Icelandic missionary drama “Godland” appears to explore identity in a very lonely place. Set in Iceland in the late 19th century, “Godland” follows Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove), an ambitious but emotionally withdrawn Danish priest, as he tries to establish a Christian church in a characteristically remote part of Iceland. The forbidding climate and attendant desolation immediately get to Lucas, who’s guided to his as-yet-unfinished church by the gruff but curious area man Ragnar (Ingvar Sigurðsson).

Soon, “Godland” takes a familiar shape, more like a tragic parable about Ragnar, a reluctant seeker, and Lucas, a stingy community leader, and their complimentary derangement and irreconcilable differences. This story, about two men who need but cannot trust each other, ultimately bookends and gives capital “M” meaning to “Godland,” the latest slow-burning mood piece by the Icelandic writer/director Hlynur Pálmason (“A White, White Day”).

Some supporting characters fill out the plot and help to establish the influence and nature of the title location, especially Carl (Jacob Hauberg Lohmann), a gruff and withdrawn local, and his two daughters: his eldest, Anna (Vic Carmen Sonne), rumored to be Lucas’ prospective wife; and Ida (Ída Mekkín Hlynsdóttir), Carl’s youngest.

Carl’s children remind us that “Godland,” like many great westerns, is about the uncertainty and tension that presides over frontier settlements. The key distinction is that “Godland” is about life on a frontier that was tentatively established sometime before these characters showed up. That’s also what the movie’s about, a poisonous colonial inheritance of suspicion, dependence, and entitlement.

Carl and Ragnar do not trust Lucas because he represents a faith and therefore a societal order that presumes to take theirs under its wing. Carl and Ragnar also want to be more like Lucas, even if he literally cannot understand them. (He doesn’t speak their language and frequently needs Anna to translate for him.) Lucas photographs the locals and even insists on taking the more arduous path from Denmark to his new home, while Carl wonders why Lucas didn’t just sail.

A diligent missionary, Lucas says he wants to get acquainted with the Icelandic people and their land. Then again, while that might have been Lucas’ goal when he set out, he’s soon changed by the harsh reality that confronts him. So Lucas unwittingly assumes the antagonistic role that Ragnar immediately projects onto him in an early scene when he tells a violent story about a woman who cheats on her husband with a group of men.

The baggage these two men drop at each other’s feet is instantly understood because it’s fairly obvious. Ragnar tries to connect with Lucas repeatedly and with startling regularity, but again, Lucas doesn’t speak his language and, more importantly, doesn’t want to. Lucas photographs his surroundings using the now antique daguerreotype process, which requires on-camera subjects to remain perfectly still for several seconds. This fussy artistic process not only helped inspire the look of “Godland”—filmed and presented in a boxy Academy aspect ratio—but also gives Pálmason a neat way to illustrate the differences between Lucas and Ragnar and their resistance to social expectations that must seem apparent to everyone but them.

Lucas, thin and shivering, fusses with his camera and stares blankly at everything he can’t control. Ragnar, plain-spoken but skittish, wants to be one of Lucas’ subjects but cannot catch the young priest’s eye. Ragnar opens up to Lucas during a beautifully shot confessional speech, but this monologue inadvertently reveals the disconnect between the filmmakers’ depth of feeling and the shallowness of this particular narrative.

Still, a few scenes and experiential details confirm the promise that Pálmason showed in the tremendous revenge drama “A White, White Day.” Hove’s skittish performance credibly expresses Lucas’ struggle to remain true to his faith and humanitarian ideals. And while Sigurðsson only hints at the depths of Ragnar’s emotions, that’s also what makes his behavior so attractive. Both men have an inner life that’s only partly revealed through episodic scenes that take place around the church and Carl’s home. But Pálmason’s latest movie comes to life whenever its characters struggle to retain their humanity and poise in the face of great, largely implied despair.

There’s just enough room for viewers to wander about “Godland” and maybe even get lost in its pregnant pauses thanks to Maria von Hausswolff’s stunning cinematography. (She also shot “A White, White Day.”) The Icelandic locations do a lot of talking for Pálmason’s characters, and they tend to speak more forcefully than either Lucas or Ragnar. Still, the big emotional finale of “Godland” is less ambiguous than one might hope for, given how much of this movie isn’t about the story, but rather the in-between moments when we struggle to be better than our past actions. The climax of “Godland” feels conclusive in ways that the rest of Pálmason’s mystery play does not, making one wish that there was an extra hour or two between its beginning and the very end.

Now playing in select theaters.