In The Atlantic last week, Conor Freidersdorf wrote, “And observing the left during the first 100 days of the Trump administration, I am beginning to despair that its pathologies are growing in strength at the very moment when the worst of the right is ascendant, too.” The phenomenon he notes, though, has the ironic upside of providing rich material for documentarians. From “Weiner,” about the New York congressman who pushed his penchant for self-display all the way to political self-destruction, to “Risk,” Laura Poitras’ portrait of the vain and self-absorbed Julian Assange (reviewed here last week), the left’s pathologies are indeed being carefully and damningly anatomized.

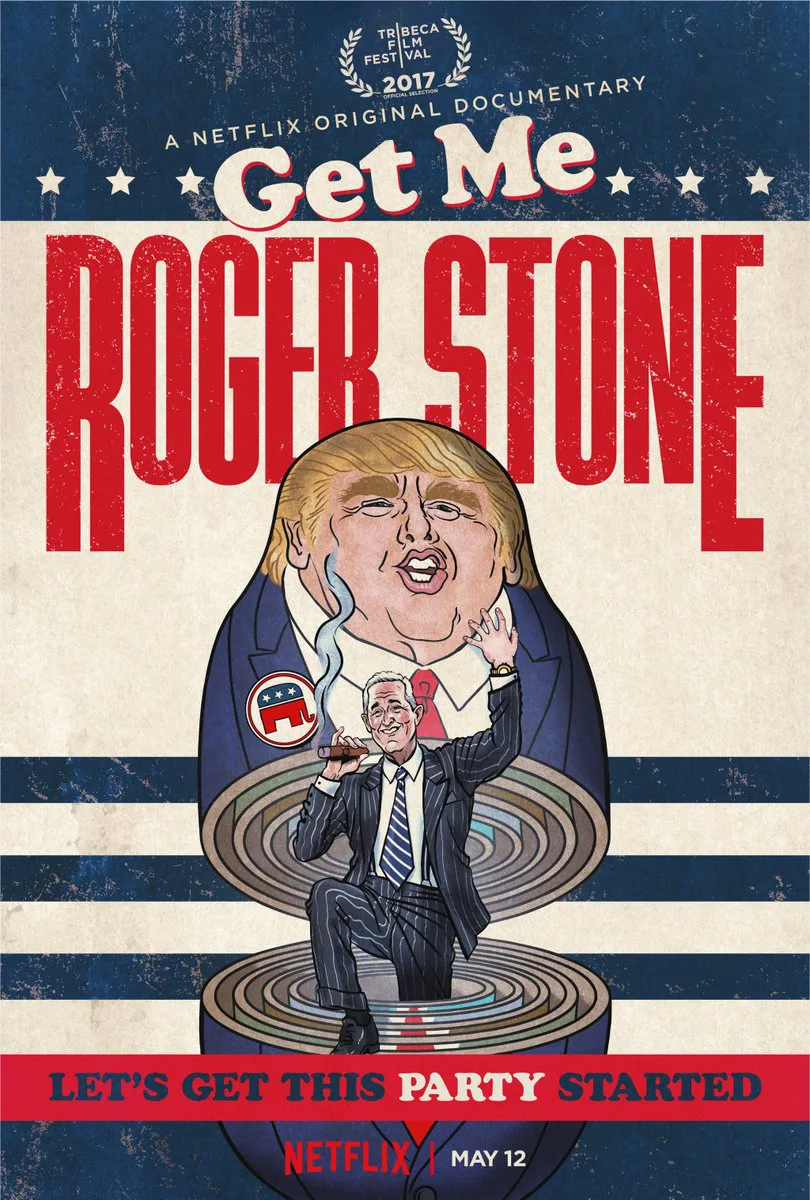

As for examining the pathologies on the opposite side of the spectrum, it’s hard to imagine any film this year will surpass the astonishing Netflix production “Get Me Roger Stone,” a documentary by Dylan Bank, Daniel DiMauro and Morgan Pehme. Stone, the right-wing self-described “provocateur” and “dirty-trickster” profiled here, may not be a name familiar even to Americans who (like this reviewer) read about politics obsessively, but the film makes the case that his career links ideologically charged figures from Roy Cohn to Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump; the latter in fact seems the logical culmination of Stone’s long campaign to remake American politics into something that would put a smile on P.T. Barnum’s face. Rather than dissecting one malaise, this film connects the dots on a sprawling network of them—it’s a veritable genealogy of pathologies.

Stone himself is our unapologetic tour guide and indefatigable explainer. He’s one odd-looking bird. With a head shaped like a melon drawn by R. Crumb and topped by some very dubious looking hair, and a gangly frame evidently bulked up at the gym and swathed in fashionable suits, he’s like a bizarre character played by John Turturro in some as yet unmade Coen brothers film. He clearly relishes talking about his favorite subject—himself—and is ashamed of absolutely nothing he’s ever done. If it increased his notoriety and gained the home team a few yards, then it was good and right.

Much of the time when he’s being interviewed, there’s a tasty-looking martini on the table next to him, and it’s tempting to think, “This guy probably would be a lot of fun to toss back a few drinks with. He’s a voluble raconteur with an evident feel for his own life’s absurdities.” But such are the snares of American politics: You can appreciate a personality’s entertainment value while being chilled at its impact on the nation.

Appropriately, the film begins and ends with Donald Trump. Stone discovered him back in the ’80s when he was looking for a political horse to race, and started grooming the real-estate mogul early on. The product of this process is in full flower in the scenes of last fall’s election, as the reality-TV star charges toward the unlikeliest of triumphs. If this were the Old Testament, Stone would be the prophet who foresaw and anointed the new king.

We then flash back to the modern prophet’s own story, which began when a teacher gave him a copy of Barry Goldwater’s The Conscience of a Conservative. Electrified, the boy threw himself into Republican politics and never looked back. Arguably the moment when Stone chose his team—the time of Goldwater and William F. Buckley—was the era when modern conservatism was at its most idealistic, principled and intellectually coherent. By the time he was in college, though, the movement had been taken over by the Constitution-subverting Nixon gang, and Stone, ever the unquestioning loyalist, found himself, at 19, the youngest person called before the Watergate grand jury.

How does he feel about that period now? Smiling, he takes off his shirt and displays the Nixon portrait tattooed on his otherwise unblemished back. Yet while providing sometime crucial support to Republican presidential candidates from Nixon to Trump, and coming up with some ingenious new ways to manipulate the media to help them (he gets some credit for the “birther” lie that helped put Trump on the map), Stone had perhaps even greater impact in other areas. His Reagan-era firm of Black, Manafort (yes, that one) and Stone helped dissolve the boundary between consulting and lobbying, and became known as “the Torturers’ Lobby” for the work it did for Third World dictators. He also founded the National Conservative Political Action Committee and pioneered the use of PACs to undermine campaign financing laws.

From helping tilt the 2000 election away from Al Gore, to working to engineer the downfall of Elliot Spitzer, Stone seems to have been everywhere, leading writer Jeffrey Toobin to dub him the “malevolent Forrest Gump” of American politics. Toobin, his New Yorker colleague Jane Mayer and the late Wayne Barrett provide much of the film’s liberal commentary, and its tone isn’t outraged but mildly astonished, even bemused, as in, “Can you believe such and such a thing Stone did.”

It would be hilarious and drolly entertaining if the consequences weren’t so appalling. With Trump’s victory, Stone seems to have reached the place he’d long dreamed of, where words have no meaning, there are no such things as truth or honesty or decency, and the only thing that counts is winning. Such is the ditch we are now in, and it’s very hard to see how we will get out. In some ways, Stone’s soul seems part carnival huckster, part 19th century anarchist. A petri dish of toxic pathologies, he has come so far from his Goldwaterite beginnings he could now write his own book: A Conservative Without a Conscience.