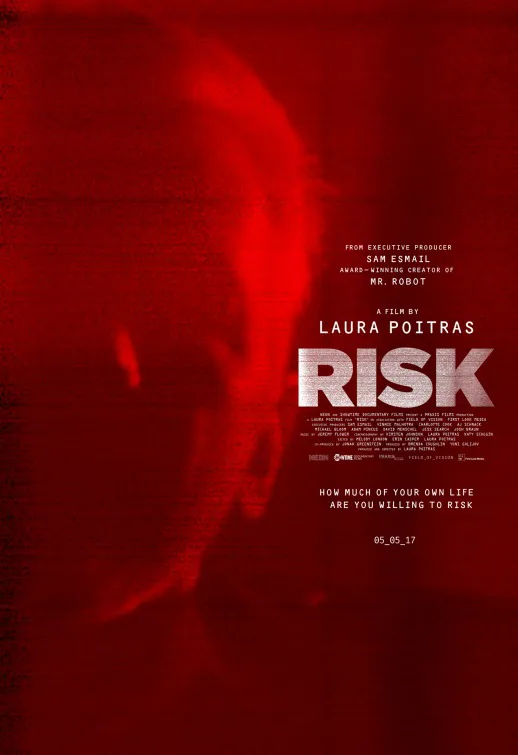

In various ways, “Risk,” Laura Poitras’ intimate look at Julian Assange and the world of Wikileaks, serves as a companion piece to “Citizenfour,” her masterful, Oscar-winning documentary about Edward Snowden. Both films benefit from the extraordinary access Poitras had to her subjects, but there are significant differences between them as well.

For one, “Citizenfour,” in being centered on the few days in a Hong Kong hotel when Snowden turned over his trove of classified documents to Poitras and two other journalists, had the tight focus and taut unfolding of a superior suspense film. “Risk,” which Poitras began shooting well before Snowden contacted her, chronicles events over seven years and thus has a looser, more episodic feel.

Second, Snowden and Assange are very different characters. While the former came across as idealistic, principled and straightforward, the latter is complicated, egotistical and cagey—but no less fascinating or determined to change the world.

The third area of difference, though, is perhaps the most subtle and crucial dimension of “Risk”: it’s in Poitras’ attitude toward her subjects. In “Citizenfour,” she mainly served as a journalist who took Snowden more or less at face value in relaying his story and revelations to the world. In “Risk,” as she gets close to Assange and his team, her personal perspective on them evolves even as their circumstances change. From initially seeming motivated by feelings of admiration and solidarity, she ends up more distanced and critical. The result is a film that Assange and his cohorts reportedly hate, even though Poitras’ portrait of them doesn’t feel remotely like an attack.

In this film as before, Poitras presents the story in verité style; aside from some conversations between the filmmaker and Assange, there are no conventional interviews or commentary by experts or outsiders, though Poitras occasionally inserts her own thoughts and moody music (by Jeremy Flower) is used to heighten the drama. This is an aesthetic approach that one can respect, even admire, even if in “Risk” it means a lack of contextualizing information that in some instances might have been very helpful.

The film is not one for any viewer who’s never heard of Assange. Indeed, it’s best suited to audiences who are familiar with the basic Wikileaks saga and thus prepared for Poitras’ much more intimate and nuanced view of events and personalities that the mainstream media tend to present in more reductive terms.

When she begins filming, in 2010, Assange and his small crew are ensconced in an elegant home in the English countryside. Wikileaks has already established its importance by releasing hundreds of thousands of classified documents concerning the U.S. war in Iraq, and the crew seems buoyed by their sense of mission and growing renown. We watch as the silver-haired Assange and his associate Sarah Harrison try to get U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on the phone to warn of an impending dump of un-redacted documents by another party. They succeed only in speaking with an underling, but Assange, while maintaining a playfully bemused attitude throughout, projects a keen sense of his own importance even at this stage.

The voice-over that Poitras uses to inject her own impressions was of course added later, but it feels like it’s registering something of her initial relationship with Assange when she says, “It’s a mystery to me why he trusts me, because I don’t think he likes me.”

It’s not long before the allegations over sexual misconduct in Sweden emerge, beginning a long ordeal for Assange that continues to this day. The Swedes say they want him shipped there only to answer questions, while his supporters believe this is only a pretext to trap and extradite him to the U.S. to face very serious charges of conspiracy and espionage. This assumption has always struck me eminently credible, and it’s obviously very important to the whole story, but Poitras sticks to her style and doesn’t interview people who might be able to speak about it authoritatively.

She also doesn’t press him to give his side of the Sweden story, though some of his feelings emerge as he talks with his associates and lawyers. These remarks are not likely to win him many fans among progressives. While some in his inner circle urge him to apologize for any offense he may have given, even unintentionally, he murmurs about radical feminist conspiracies and women involved in a lesbian nightclub. Eventually, of course, he exhausts his options in the British courts and takes political refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, where he remains.

“This is not the film I thought I was making,” Poitras intones after listening to Assange’s comments about the Swedish imbroglio. “I thought I could ignore the contradictions. I was wrong … They are becoming the story.” As indeed they do.

Into the Assange/Wikileaks chronicle Poitras skillfully and appropriately weaves narrative glimpses at other aspects of the unfolding cyber-activism story. We see Daniel Ellsberg denounce as “outrageous” the military’s mistreatment of whistleblower Bradley (later Chelsea) Manning, who is given the harshest sentence ever for leaking to the media. In 2013, Poitras goes off to meet Edward Snowden, leaving Assange miffed that the documents were leaked to the MSM, not him. Earlier, during the Arab Spring, we witness activist Jacob Appelbaum (who was featured in “Citizenfour”) boldly accusing Egypt’s media and technology leaders of serving the regime rather than the people.

At last spring’s Cannes Film Festival, Poitras showed a version of “Risk” which lacked elements that now serve as the film’s final act. These include showing Assange express his distaste for Hillary Clinton, whom he regards as an enemy and a “warmonger.” Later, when Wikileaks leaks documents damaging to the Democrats, Assange is accused of cooperating with the Russians in order to sway the U.S. election. He denies the charge, maintaining the he was not dealing with a “state actor.” Meanwhile, Appelbaum—with whom Poitras admits having a brief affair—is forced out of the nonprofit where he worked due to charges of abuse and sexual misconduct.

Given that questions regarding Russian interference in the 2016 election remain open, and that Appelbaum declined to be interviewed for “Risk,” the film’s ending has an air more of disarray and dismay than of resolution. It did not, however, leave this viewer feeling that people with serious character flaws (narcissism, megalomania, sexual compulsion, what have you) cannot to do great and important things in the world. Rather, the film points up the need to draw clear distinctions between personalities and issues; the former may dominate the tabloids but the latter determine our lives. In any case, “Risk” is another fascinating piece of cinema-as-history that reminds us that Laura Poitras remains one of our most original, courageous and valuable filmmakers. It is a film that will be prompting debate and study for years to come.