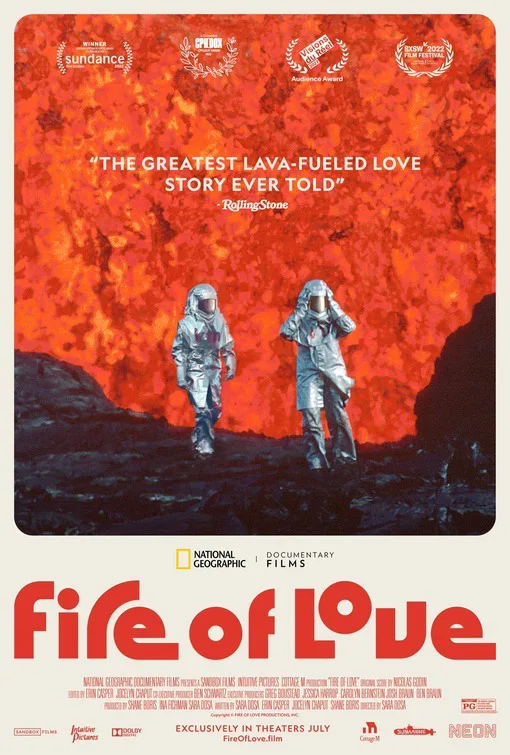

A poem of matrimony and magma, “Fire of Love” is about Katia and Maurice Krafft, a married team of volcanologist-filmmakers. The Kraffts were known for their inventive exploration and photography of active volcanoes. Their work started in the late 1960s and ended in 1991 when a pyroclastic flow on Japan’s Mt. Unzen wiped them out along with a group of 41 scientists, firefighters, and journalists.

Note that in the preceding sentence, “short” was not preceded by “tragically.” Maurice Paul Krafft and Catherine Joséphine “Katia” Krafft were Alsacian French volcanologists who were inseparable the moment they discovered that they shared an obsession with fiery earth. They knew the risks of their chosen field and accepted them.

“I want to get closer, right into the belly of the volcano,” Maurice once said, adding, “It will kill me one day, but that doesn’t bother me at all.”

“It’s not that I flirt with death,” Katia said, “but at that moment, I don’t care at all.”

Their union not only produced a trove of astonishing imagery that can be endlessly reworked and put to a variety of uses, it gave any future filmmaker who wanted to retell their story a gallery of metaphors for love, passion, obsession, and commitment. From the opening images of the Kraffts driving a Jeep through snowy tundra and pausing to unstick the vehicle from an ice patch, shot after shot serves its own narrative function while seeming as if it’s also functioning as a metaphor or symbol (regardless of the Kraffts’ original intent). Films that are made this way can be endlessly re-watchable, because they don’t put too fine a point on the various possible secondary associations, instead giving the viewer mental space in which to muse and fantasize and draw their own connections.

Directed and cowritten by Sara Dosa (“The Last Season,” “The Edge of Democracy“) and narrated by filmmaker-actor-artist Miranda July, “Fire of Love” is one of a vanishingly rare breed of documentary that is determined to be “total cinema,” not just capturing the facts of what happened to its subjects but creating an entire aesthetic—a vibe—around them. As directed by Dosa and nimbly cut by editors Erin Casper and Jocelyne Chaput (who have already received an award for their work here, and deserve more), “Fire of Love” is not content to toss a series of arresting images collected by other filmmakers on the screen, even though the result still would’ve been riveting if they had.

The Kraffts were once described by a journalist as “traveling performer volcanologists,” and they liked the description and found truth in it. Dosa’s movie leans into the idea, linking them to a long tradition of naturalist filmmakers that includes their countryman Jacques Cousteau. We’re aware that the Kraffts are using their eccentric charisma and romantic mystique to get themselves (and the viewer) as close to the action as possible. Our awareness of the mechanics of their “act” is part of the show we’re watching, like the patter of a magician who talks about the history of illusions while doing tricks.

Werner Herzog told the Kraffts’ story in “The Fire Within” and “Into the Inferno,” but in a less cohesive and fully realized way. Herzog’s late-career work as a nonfiction filmmaker sometimes has a slapped-together feeling (except in “Grizzly Man,” a film with a brutal, telegraphed-in-advance ending that Dosa’s movie evokes). That’s never the case here. Just when the narration threatens to turn a Herzogian shade of purple, it stops short and defers to the imagery, as if trusting that whatever thoughts we might have about the Kraffts and the images they captured will be more edifying than an omniscient narrator’s attempt to sum things up for us.

The artists have made something paradoxically unassuming yet grand—a movie with a churning, flowing, volatile life force, befitting the topic that obsessed the Kraffts. Like “Apollo 11,” “The Velvet Underground,” “Summer of Soul” and other esteemed predecessors (including Godfrey Reggio’s visually driven, quasi-experimental documentaries) this is a nonfiction film that could be shown in IMAX and advertised as pure spectacle. This writer saw it on a laptop and was mesmerized by it, but would love to see it projected on an enormous screen someday.

It is never more graceful and on-point than when it’s serving up a succession of nature images captured by the Kraffts: a still image of a hand caressing ripples in black earth; expressionistic shots of lava-fountains spewing; underwater images of red-hot magma extruding and then cooling and hardening. “Fire of Love” has an identity that is connected to, yet independent of, the information it delivers. Pedro Almodovar once advised new filmmakers that it isn’t enough for a film to move: it needs to dance. This movie dances. You could project it on the wall of a nightclub.

The movie never succumbs to self-infatuated grandiosity, probably because it’s impossible to stare at images of the earth continually destroying and re-creating itself without realizing how small we are. “The human eye cannot see geologic time,” Krafft says at one point. “Our lives are just a blink compared to the life of a volcano.” Does that mean that the Kraffts’ great love is diminished? Probably they’d say yes; they were humble about their importance in the greater scheme.

But directors keep making movies about them. And as the title of this one suggests, it’s not just the images of erupting and flowing and cooling lava that draws them.

Now playing in theaters.