“There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that is making war, and we’re winning.”—Warren Buffett

You’ve likely heard this quote before, just as you may be familiar with Alexandre Desplat’s Oscar-winning score for “The Grand Budapest Hotel.” Yet each achieves a newfound resonance when filtered through the collage-like vision of Petra Costa, a Brazilian auteur who has proven adept at weaving histories both global and familial into the fabric of her dreamlike elegies. Like her brilliant 2012 debut feature, “Elena,” which recounted the “inconsolable memory” of Costa’s older sister prior to her suicide, the director’s latest work, “The Edge of Democracy,” is haunted by loss.

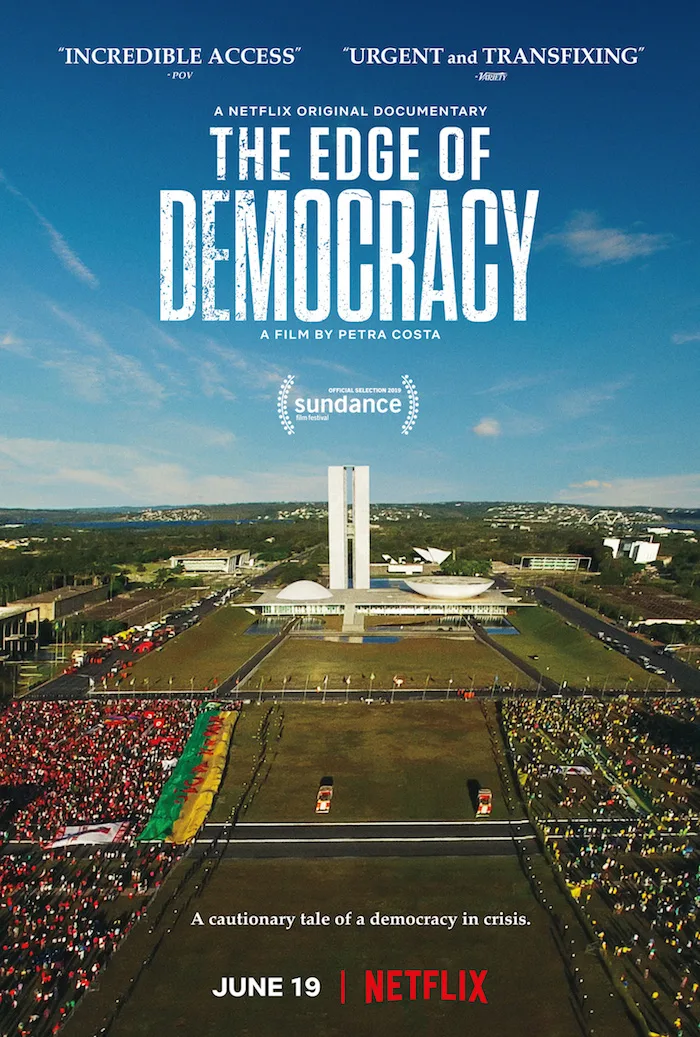

It seeps through every syllable of Costa’s entrancingly melancholic narration, as she mourns the once gleaming potential rendered unreachable in the lives of her loved ones, and society as a whole. In lesser hands, this sort of subject matter could’ve easily resulted in a sluggish dirge, but the 35-year-old documentarian seems utterly incapable of crafting a frame that is lacking in urgency or vibrance. If anything, the pace of her storytelling is so breathless that it makes her new film a natural fit for Netflix, where viewers unfamiliar with the recent troubling developments in Brazil can rewind and select closed captioning when needed to alleviate any confusion.

As a rebuke to the rising tide of fascism around the world, Costa juxtaposes the arc of her own life with that of her country, framing Brazil’s misogynistic dictatorship through her empowered, formidably insightful perspective. The rigorously personal nature of Costa’s narratives is, in itself, a political statement not unlike the one made by Nanfu Wang, who revolts against China’s prioritization of the collective over the individual with first-person exposés like “Hooligan Sparrow” and the upcoming “One Child Nation.” From the very beginning of her third feature effort, Costa illustrates how she came of age alongside Brazilian democracy after their respective births in 1984.

She was named by her militant mother after Pedro Pomar, one of many leftist party leaders killed during Brazil’s previous military dictatorship, a period that lasted nearly 21 years. One of its greatest foes was Lula da Silva, a union leader who became interested in politics upon learning that only two of the nation’s several hundred congressmen were working class. At age 19, Costa happily cast her first ballot for Lula, whose fourth bid for the presidency in 2002 was victorious, thanks in part to his friendlier disposition toward businessmen. Though the filmmaker hails Lula’s achievements—including the success of his social welfare program, Bolsa Família, that brought 20 million citizens out of poverty—she also doesn’t shy away from acknowledging his distressing allegiance with the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), dubbed by Costa as her country’s “oldest oligarchy.”

It’s impossible not to be reminded of the dishonest methods utilized by the Democratic National Committee that played a crucial role in its loss during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, especially when “The Edge of Democracy” sheds light on how corruption fueled by campaign financing caused the Worker’s Party, founded by Lula, to erode from the inside. An example of Costa’s poetic ingenuity occurs early on, as she notes how Brazil was named after the “brazilwood” trees, which have been harvested into near-extinction because of the red dye that it yields to high demand. The trees’ crimson hue is echoed in the red flags of the Worker’s Party, serving as the lifeblood of Brazilian democracy until it, too, wound up on the list of endangered species.

A series of anti-corruption laws enforced by the country’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, a former guerrilla fighter anointed by Lula as his successor in 2011, inadvertently triggered Operation Car Wash, an ongoing investigation involving alleged bribes at the state-controlled oil company, Petrobras. Both Lula and Rousseff were indicted in the charges, thereby making it appear as if oil, rather than blood, coursed through the veins of their party. After narrowly winning her second term in office, Roussef’s opponent, Aécio Neves, refuses to accept the election results, claiming that he lost to a “criminal organization” while stoking the flames of a coup in the guise of impeachment proceedings. Despite being distantly related to the director—“His mother married my grandfather’s cousin,” Costa explains—Neves declines to be interviewed, thus causing him to emerge as the Roger Smith (the General Motors CEO who famously refused to be interviewed for Michael Moore’s “Roger & Me”) of this muckraking opus.

The startling level of access Costa and her cinematographer João Atala are granted to Lula and Rousseff throughout the ensuing scandal goes a long way toward humanizing their plight without ever fully letting them off the hook. The footage here is every bit as revealing and chillingly timely as what is contained in Vitaliy Manskiy’s yet-to-be-released “Putin’s Witnesses,” an essential, on-the-ground profile of the future Russian president and the disillusionment spawned by regime shifts marked by betrayal. Take, for example, the conspicuous gap noted by Costa that exists between Rousseff and her conservative vice president, Michel Temer, as they walk together on election day. His desire to take her place was already blatant at the outset, and when he praises Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016 as a “religious act” built around “fundamental values,” you can almost hear the super PACs behind “God’s Not Dead” applauding.

Of course, the same government officials who voted to impeach Rousseff block an investigation of Temer once his own corrupt acts are exposed. Costa replays excerpts of two damning audio leaks that further underline the inherent hypocrisy in right wing supremacy and its supposed moral righteousness. She also unearths an interview with another bribe-taking politician, Eduardo Cunha, admitting on camera that the grounds for impeaching Rousseff were unfounded, before later pushing for her removal. Claims made by other politicians, interviewed by Costa, that Rousseff wasn’t well-liked because she “didn’t give enough hugs” seem like a thinly veiled cover for how her diligence in holding bankers accountable likely led to her unpopularity. As we witness a swarm of white male legislators gleefully celebrating Rousseff’s absence, Costa’s voice-over scathingly addresses how “defenders of the Bible, the bullet and the bull seized the saloon with thirst.”

Chief among the homophobic, gun-loving, evangelical-courting government officials is Jair Bolsonaro, the man now serving as Brazil’s president, whose exaltation of the past dictatorship and promise to defend the market interests of his peers seals his reputation as the country’s closest equivalent to Donald Trump. We first see him flaunting his political victory like a schoolyard bully, relishing the opportunity to tear a ballon of Lula decked out in prison garb to shreds. These helium-filled weapons of propaganda grow frighteningly in number and stature as the film progresses, signaling how a baseless act of political assassination has been reduced to ratings-driven entertainment by the press, with newspapers likening recently disgraced Judge Sérgio Moro’s interrogation of Lula to a boxing match.

One of the defining aspects of our current political era is the normalization of previously unthinkable headlines, obscuring our outrage in a haze of inevitability. Proven facts have been trumped by sensationalistic memes, causing Lula to be thrown in prison without any irrefutable evidence being presented. “Tell me what crime I’ve committed!” Lula pleads to Moro in a Kafkaesque courtroom sequence that could’ve been lifted directly from The Trial, the doomed protagonist of which—Josef K.—Rousseff laughingly compares herself to, while surveying the obliteration of her legacy with bemused resilience. Her poise, further strengthened after surviving years of torture, remains intact as she speaks to a roomful of naysayers, insisting that she fears only the death of democracy. Equally wrenching is Lula’s stirring speech to distraught supporters prior to his arrest, where he affirms that ideas, unlike people, cannot be imprisoned.

What’s perhaps most striking about the film’s concluding moments is that they are largely wordless, as Bolsonaro’s supporters celebrate his election win while clad in Trump masks. Turns out the wall erected to separate citizens favoring Rousseff’s impeachment from those opposing it also runs through Costa’s own family, with her activist parents on one side and the relatives who helped elect Bolsonaro—a tyrant who would surely have put Costa’s parents to death during the dictatorship—on the other. Though water doesn’t resonate as a motif in “The Edge of Democracy” like it does in “Elena,” it is the encroaching floodwaters brought about by climate change that are likely triggering mankind’s collective backsliding into authoritarianism.

Religion is what humans cling to in times of desperation, and it will always be exploited by those in power unwilling to let go of their oil-fueled profits, even if it results in our world gradually being submerged, a la the Titanic. After all, a reduced population will result in less clamoring for the earth’s limited resources. With the sixth mass extinction already underway, we have two options—unite as one human family and fight for our survival, or build barriers to otherize refugees while embracing our impending demise as godly salvation. By launching her film this week on a global streaming platform, Costa is reminding us all that if the rich are not threatened, an oligarchy will take over. And as Buffett deftly observed, the rich are winning.