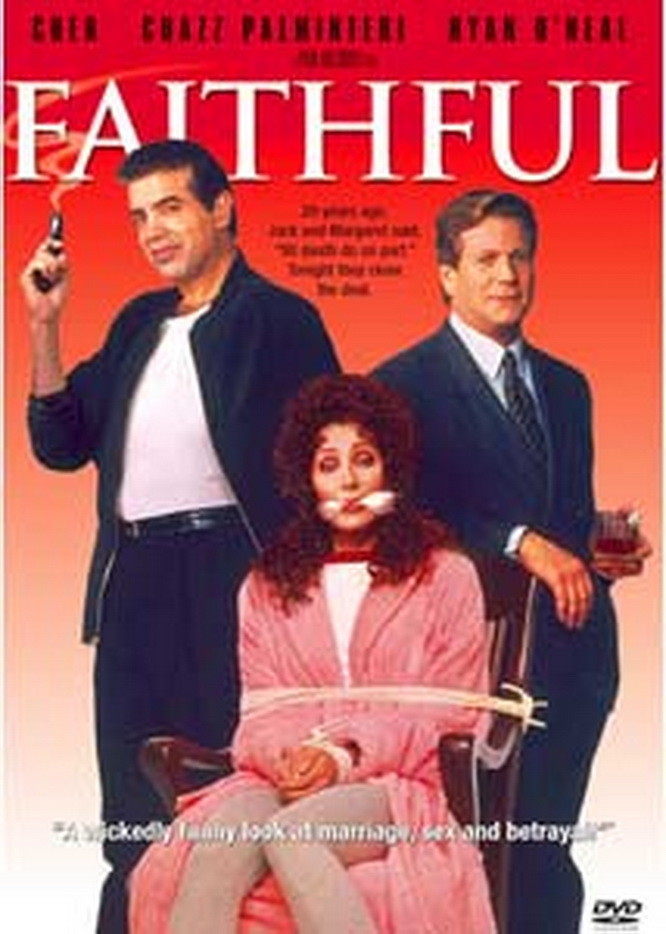

It’s a hell of a note: “Two people get married in church and one of them hires a stranger to kill the other.” This dialogue comes midway in “Faithful,” a story about a faithless husband (Ryan O'Neal) who hires a hit man (Chazz Palminteri) to murder his wife (Cher). The fact that it comes midway will give you a clue to the construction of the film, which is more about dialogue than it is about husbands, wives or killers.

The film is based on a stage play by Palminteri and has been filmed by Paul Mazursky with a few attempts to open up the action, such as a shopping trip by Cher and a glimpse of O’Neal at work (he’s having an affair with a younger woman). But mostly the action takes place inside the couple’s enormous home, where every room becomes another set after Palminteri breaks in, ties Cher to a chair and waits for the signal to kill her.

The signal will be two rings of the telephone; O’Neal plans to call home after he’s safely in Connecticut with an airtight alibi. I don’t think much of it as a signal.

What if somebody else calls and hangs up, or what if O’Neal changes his mind? The phone signals get more complicated after Palminteri calls his shrink (played by Mazursky), who is to call back and ring only once. A few more callers, and this plot would require Groucho Marx.

When I said the movie was mostly about dialogue, I mean that seriously. There is never a moment when we think Cher is in serious danger, or that there’s any likelihood Palminteri will kill her. The rules are too well-established in plots like this. The killer starts talking to his victim, they begin to like each other, and one thing leads to another. Only rarely, as in last year’s “Bulletproof Heart,” with Anthony LaPaglia and Mimi Rogers, is there a surprise at the end.

Palminteri is good with dialogue, and the exchanges he’s written for the hit man and target are clever in their twists, as when Cher tries to save herself by attempting to(a) seduce Palminteri, (b) convince him that she, not her husband, hired him, (c) bribe him, and (d) hire him to kill her husband after he kills her.

They even talk about love. “I was in love once,” Palminteri tells her.

“What happened?” “It didn’t work out. I had to kill her father.” Then O’Neal returns home, and Palminteri has some fun with various stage techniques, such as the puzzle of the missing person; the third act keeps us in doubt about what has happened, and why, and to whom, while Cher and O’Neal deconstruct their marriage.

“Faithful” is the kind of movie that’s diverting while you’re watching it, mostly because of the actors’ apeal, but it evaporates the moment it’s over, because it’s not really about anything. Nothing is at stake, the relationships are not three-dimensional enough for us to care about them, and it’s likely that nobody will get killed. That leaves the physical presences of the actors and the wit of the dialogue–enough for a play, but not for the greater realism of a movie.