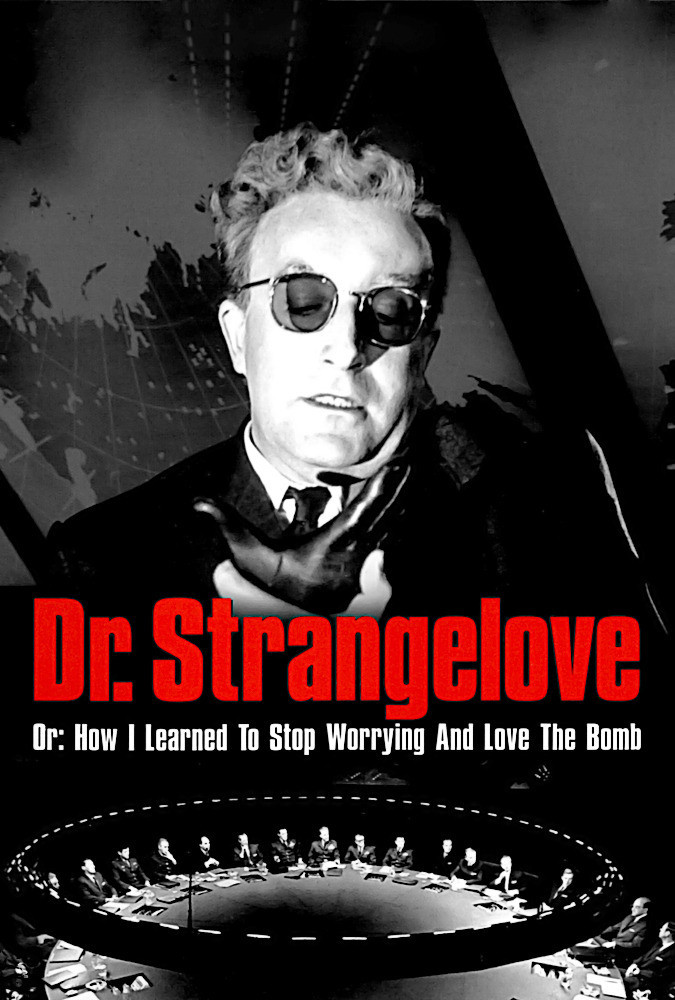

In the days after it first opened in early 1964, Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” took on the enchanted aura of a film that had gotten away with something. Johnson was in the White House, the Republicans were grooming Goldwater, both sides took the Cold War with grim solemnity, and the world was learning to be comfortable with the term “nuclear deterrent,” which meant that if you blow me up, I’m gonna blow you up, and then we’ll all be dead. “Better dead than Red,” some said. Others said the opposite. The choice was not appealing.

The Bomb overshadowed global politics. It was a kind of ultimate hole card in a game where the stakes were life on earth.

Then Kubrick’s film opened with the force of a bucketful of cold water, right in the face. What Kubrick’s Cold War satire showed was not men at the mercy of machines, but machines at the mercy of men – especially the loony Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden).

Commanding a wing of the Strategic Air Command, he orders the B-52 bombers under his command to attack the Soviet Union. When an aghast British military attache (Peter Sellers) tries to stop him, Ripper sucks on a huge phallic cigar while explaining the Commie plot to taint our water supply and deplete our “precious bodily fluids.” He refuses to reveal the code which could recall the nuclear-armed planes, and eventually shoots himself while the world careens toward doom.

Events on Ripper’s army base are intercut with scenes on board one of the B-52s, and with an emergency meeting in the Pentagon’s War Room – still one of the most memorable sets ever constructed for a movie, with its vast global maps looming over a huge round table with an unblinking circle of light above it. Here U.S. President Merkin Muffley (Sellers again) learns with horror from his strategic adviser Dr. Strangelove (Sellers in his third role) that the Russians have a Doomsday Machine, set to launch a counterattack if the Soviet Union is bombed. It appears that neither the Doomsday Machine nor one of the U.S. bombers can be dissuaded from their missions.

The movie’s screenplay, by Terry Southern with help from Kubrick and Peter George, fashions this scenario into a dark comedy of errors, illuminated by flashes of brilliant satire. Some of the dialogue has entered the language – “precious bodily fluids,” of course, and also the way the dim-witted Col. Bat Guano (Keenan Wynn) hints darkly of Commie “preverts.” The scene at the telephone booth between Guano and the British attache, who does not have the correct small change to call the White House and save the world, is one of the movie’s best-constructed gags.

If Sterling Hayden makes a glowering, paranoiac Gen. Ripper, George C. Scott is brilliant as his counterpoint, Gen. Buck Turgidson, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who chews gum, makes faces, and breaks one piece of bad news after another to the President. And Sellers, as president, has a series of painfully labored hotline conversations with the Soviet Premier (“He went and did a funny thing, Dimitri . . .”) that reduce nuclear annihilation to the level of a very serious social gaffe.

At about the same time Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 was showing the way language can be tortured into new shapes and meanings, “Dr. Strangelove” had the same kind of verbal wit: “The auto-destruct mechanism destroyed itself,” we learn, and “You can’t fight in the War Room!” And in contrast to the abstract debates in the Pentagon, there’s the simple patriotism of the B-52 pilot, Maj. “King” Kong (Slim Pickens), who promises his crew there’s going to be promotions and decorations all around. His exit from the movie, riding a bomb like a bronco, remains one of the most famous moments in modern film.

The only part of the film that doesn’t really work is the War Room sequence that comes between Pickens’ wild ride and the closing nuclear montage. Sellers, as Strangelove, battles hilariously with his misbehaving bionic hand, but the dialogue doesn’t seem to lead anywhere, and the sequence seems oddly inconclusive. In an earlier shot in the War Room, we’ve seen a long table covered with cakes and pies, and it’s said Kubrick intended to end the scene with a pie fight. I’m happy that he didn’t, but maybe he could have moved the whole scene earlier; after Pickens rides that bomb to the ground the only possible segue is to all those mushroom clouds.

Seen after 30 years, “Dr. Strangelove” seems remarkably fresh and undated – a clear-eyed, irreverant, dangerous satire. And its willingness to follow the situation to its logical conclusion – nuclear annihilation – has a purity that today’s lily-livered happy-ending technicians would probably find a way around. Its black and white photography helps, too, putting an unadorned face on its deadly political paradoxes. If movies of this irreverence, intelligence and savagery were still being made, the world would seem a younger place.