Some jerk sent me an e-mail revealing the secret of “Double Jeopardy.” It’s a secret the movie’s publicity is also at pains to reveal. I know it’s an academic question, but I’ll ask it, anyway: Why go to the trouble of constructing a screenplay that conceals information if you reveal it in the ads? Once tipped off, are we expected to enjoy how the film tells us what we already know? If through some miracle you have managed to avoid learning anything about “Double Jeopardy,” you might want to stop reading after my next sentence. This is the sentence, and it advises you: not a successful thriller, but with some nice dramatic scenes along with the dumb mystery and contrived conclusion; not the best film opening this weekend (that would be “American Beauty,” or “Mumford,” or, what the hell, give yourself a treat and go see “Genghis Blues“).

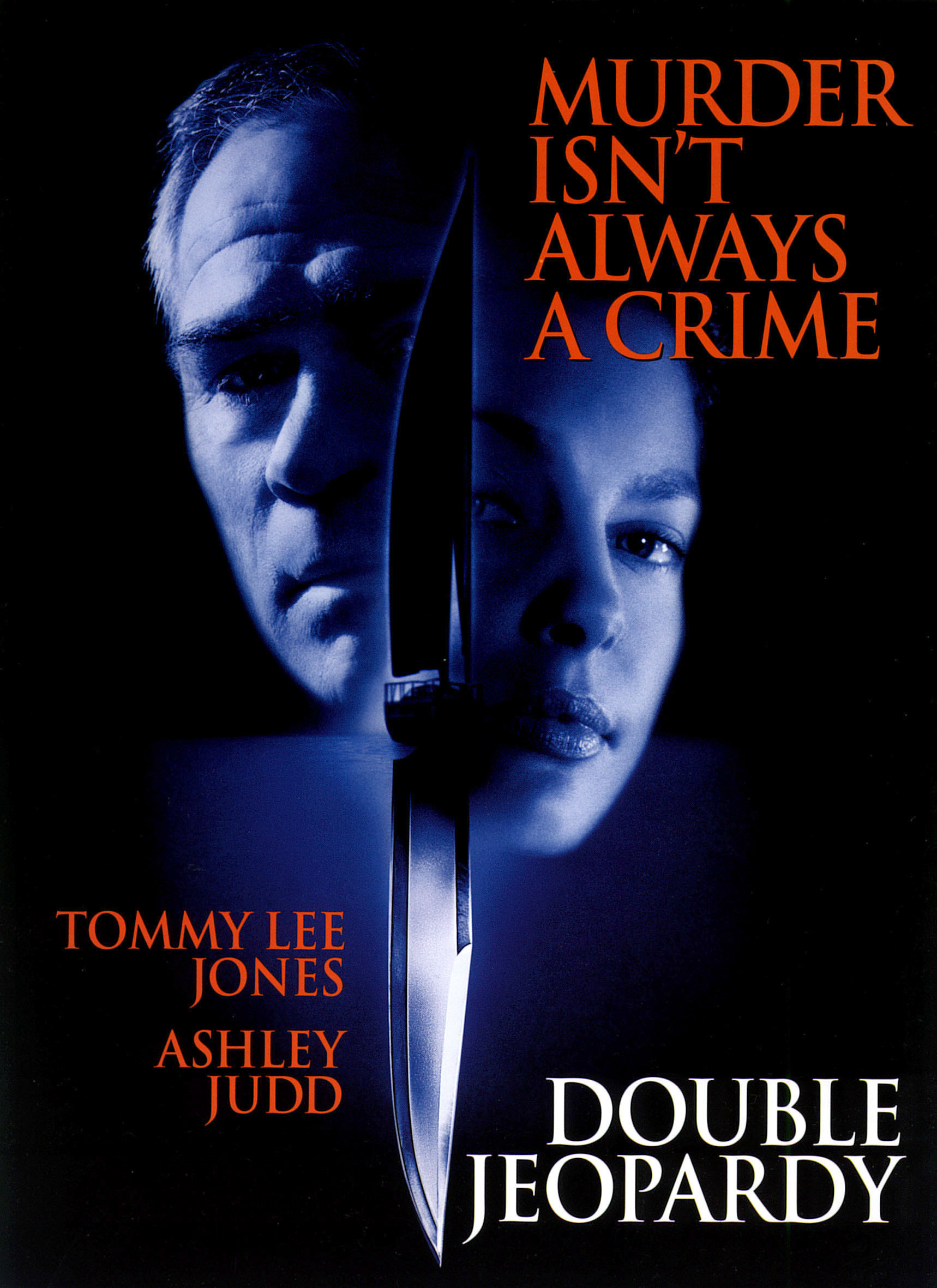

Now that the idealists have bailed out, the rest of us can consider “Double Jeopardy,” which stars Ashley Judd as a woman named Libby, who thinks she is happily married until, and I quote from the first sentence of the Paramount press release, she is “framed for the murder of her husband.” This is, come to think of it, not such a surprise anyway, considering that Judd is pure-faced and clear-eyed, and her husband is played as a weasel. When they go sailing and the Coast Guard finds her in a blood-soaked nightgown on a blood-smeared deck with a knife in her hand, we make an intuitive leap that she isn’t a slasher. (The movie’s trailer provides a helpful hint: “Libby Parsons is in prison for a crime she didn’t commit!”) The whole business of how she was framed, and how she tries to find her husband and regain custody of her child, is basically just red meat the director throws to the carnivores in the audience. You know and I know and anyone over the age of 10 knows that the movie is not going to end without that kid back in Libby’s arms, probably with some heart-rending music. What makes the film interesting isn’t the story, but a prison sequence and a relationship.

Libby in prison is befriended by a couple of women prisoners, who killed their husbands, but are otherwise the salt of the earth. They create a nice dynamic. Not as realistic and evolved as Sigourney Weaver’s startling jail scenes in the forthcoming “Map Of The Human Heart,” but not bad for a genre picture. One of the prisoners gives her an interesting piece of legal advice: Since she has already been tried and convicted for the murder of her husband, she cannot be tried for the same crime twice. Therefore, “You can walk right up to him in Times Square and pull the [I must have missed a word here] trigger and there’s nothing anybody can do about it.” Caution, convicted killers: I am not sure this is sound legal advice. I believe the constitutional protection against double jeopardy has a couple of footnotes, and I urge you to seek legal advice before reopening fire. It’s good enough for Libby, however, and when she gets out of prison, she determines to find her betraying louse of an ex-husband and their child.

She’s assigned to a halfway house, where her parole officer is a hard-bitten man of few and succinct words, played by Tommy Lee Jones. And their scenes together are good ones. When she feeds him the same heartfelt lines that worked with the parole board, he barks, as only Tommy Lee Jones can bark, “I’m not interested in your contrition. I’m interested in your behavior. Get out of here and behave yourself.” How Jones and Judd find themselves underwater is a little unlikely, but so what. As you know from the ads, at one point she’s handcuffed to a sinking car. At another point, a terrifying thing happens to her in a New Orleans cemetery. And there is a charity auction of society bachelors at which she makes some Hitchcockian moves. Someday you may have to rent the video and play it at slo-mo to figure out how everything happens in the big climax, but by then the movie is basically just housekeeping, anyway.

“Double Jeopardy” was directed by Bruce Beresford. He and Ashley Judd and Tommy Lee Jones have all been involved in wonderful films in the past–films that expand and inspire, like “Tender Mercies” and “Driving Miss Daisy” (Beresford); “Ruby in Paradise” and “Normal Life” (Judd), and “The Executioner’s Song” and “JFK” (Jones). This movie was made primarily in the hopes that it would gross millions and millions of dollars, which probably explains most of the things that are wrong with it.