Sometimes a man and woman are drawn together precisely because they are perfectly wrong for each other. Consider Pam and Chris Anderson, the subjects of “Normal Life.” He is a suburban Chicago cop. She is a pot-head who works in a factory, drinks too much, and dreams of falling into a black hole so that her image is forever imprinted on its event horizon.

They meet in a bar. Pam’s with a guy. They have a fight. She smashes a glass and cuts herself. The guy leaves. Chris walks over, helps her bandage the cut, and says, “Want to dance?” It’s awkward dancing with your hand held up in the air so the blood doesn’t drip, but she accepts. It’s love. They marry.

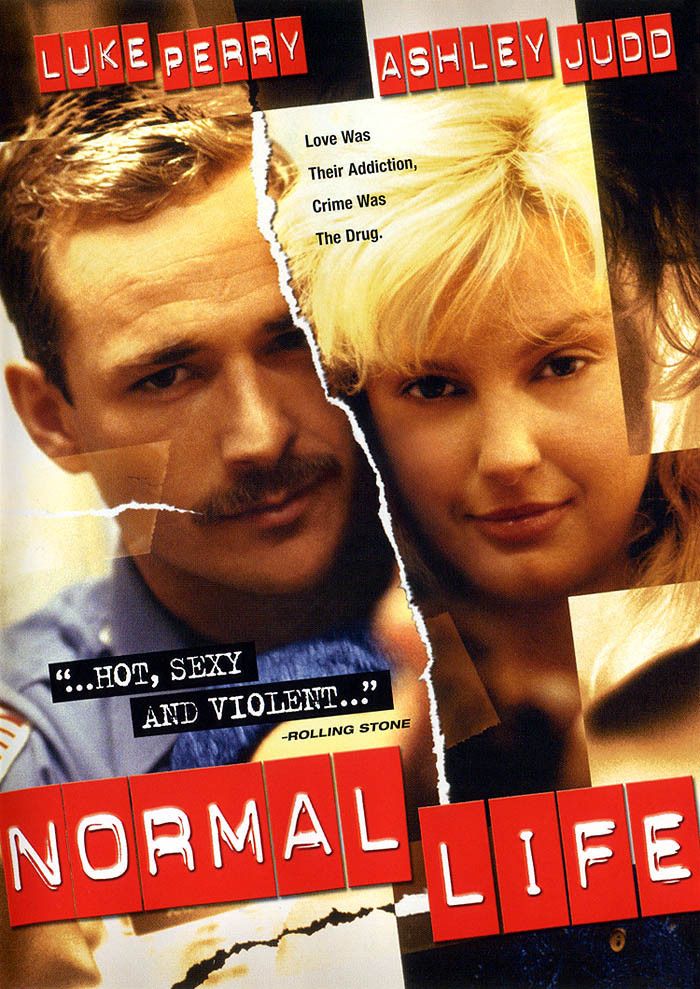

“Normal Life,” loosely based on a real-life crime story from the Chicago suburbs, is the new movie by John McNaughton, famous for “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” It’s not as unremittingly painful as the earlier film, but just as fascinating in its portrait of criminal pathology. Just as Henry drew accomplices into the net of his madness, so does Pam (Ashley Judd) mesmerize Chris (Luke Perry). He’s a straight-arrow policeman whose hobby is target practice. She’s a space cadet whose hobby is astronomy and who is reading, or pretending to read, A Brief History of Time.

Pam is one of those women who is forever pushing the edges of her own personal event horizon. She is drunk a lot, hysterical, manic-depressive, and self-destructive. She tears up the apartment, mutilates herself, tries suicide and specializes in embarrassing Chris (she walks into the police station dressed in hot pants and turns up at his father’s funeral on in-line skates).

Chris puts up with this because he must. Something in his makeup has addicted him to–what? The excitement? The abuse? The role of rescuer? “I just want to make you happy,” he says. After he gets fired, he works a double shift at a security service, but she spends faster than he can earn. So he robs a bank. He’s good at robbing banks, and soon he’s able to show her the bright new townhouse in Lisle that he’s bought with the money.

As for Chris, he gets his dream, too–which is to operate his own used-bookstore. Eventually, of course, she finds out what he’s doing–and is so excited by the idea of his crimes, she has a sexual climax for the first time in her life. She wants to come along on the next job, and although Chris knows in his bones that it is a big mistake, he lets her. You may vaguely remember the outcome from headlines a few years ago.

This is one of those movies you watch with the same fascination as a developing traffic accident. Part of its success is due to the casting. Ashley Judd, so warm and likable in “Ruby in Paradise” (1993), here plays the kind of woman you would cross the room, or the state, to avoid. Luke Perry, who has a neat cop-style mustache and an obsession with control, is the perfect foil as a man who has never seen anything like her, and can’t stop looking.

“Normal Life” takes place against the very normal backdrop of Chicago’s western suburbs. Pam and Chris eat in fast food places, shop in stores with “BUY MORE!” painted on the walls, rob drive-up banks, and when they fight, they do it while stalking down the deserted sidewalks of a mall in the middle of the night. They look, at first glance, like your typical young married couple. But on the basis of this film, my guess is that after their crime spree ended and the press came to interview their neighbors, nobody said, “Gee, they were always so quiet and nice.” McNaughton seems fascinated by the ways in which lawlessness is infectious. In both “Henry” and “Normal Life,” there are characters who would never commit a crime on their own. But once they fall under the spell of a reckless or heedless outlaw, they are helpless to resist. The lesson, I guess, is that if you see someone in a bar cut themselves while breaking up with their last lover, let them bleed.

Note: “Normal Life” got caught in a quarrel between its studio, Fine Line, and McNaughton. The studio decided not to release the film theatrically, and aired it on Home Box Office not long ago. Now, after McNaughton’s protests, it is being given a limited chance to prove itself in Chicago and a few other markets.