Does every moment of a movie have to work for you? Or can you enjoy an imperfect one if it fills in places around the edges of your imagination? “Don’t Come Knocking” is a curious film about a movie cowboy who walks off the set, goes seeking his past, and finds something that looks a lot more like a movie than the one he was making. There are scenes that don’t even pretend to work. And others that have a sweetness and visual beauty that stops time and simply invites you to share.

The opening shot is the key. On a black screen, we see two openings into the sky. From how they’re placed, they could be the eyeholes in a ragged mask, maybe the Lone Ranger’s. Then the shot reveals itself as a rock formation in Monument Valley; millions of years of evolution have left behind these two holes, joined by arches to the walls of a long-ago river canyon.

We are looking into the past, and at icons of the movie Western; such rock formations were a backdrop in the classic films of John Ford. But the movie being filmed is far from “Stagecoach.” The mobile homes of the filmmakers are arranged in a circle, like wagons, but instead of a horse the assistant director rides a Segway. The Western being made is so bad in a retro Johnny Mack Brown way that maybe it’s a satire.

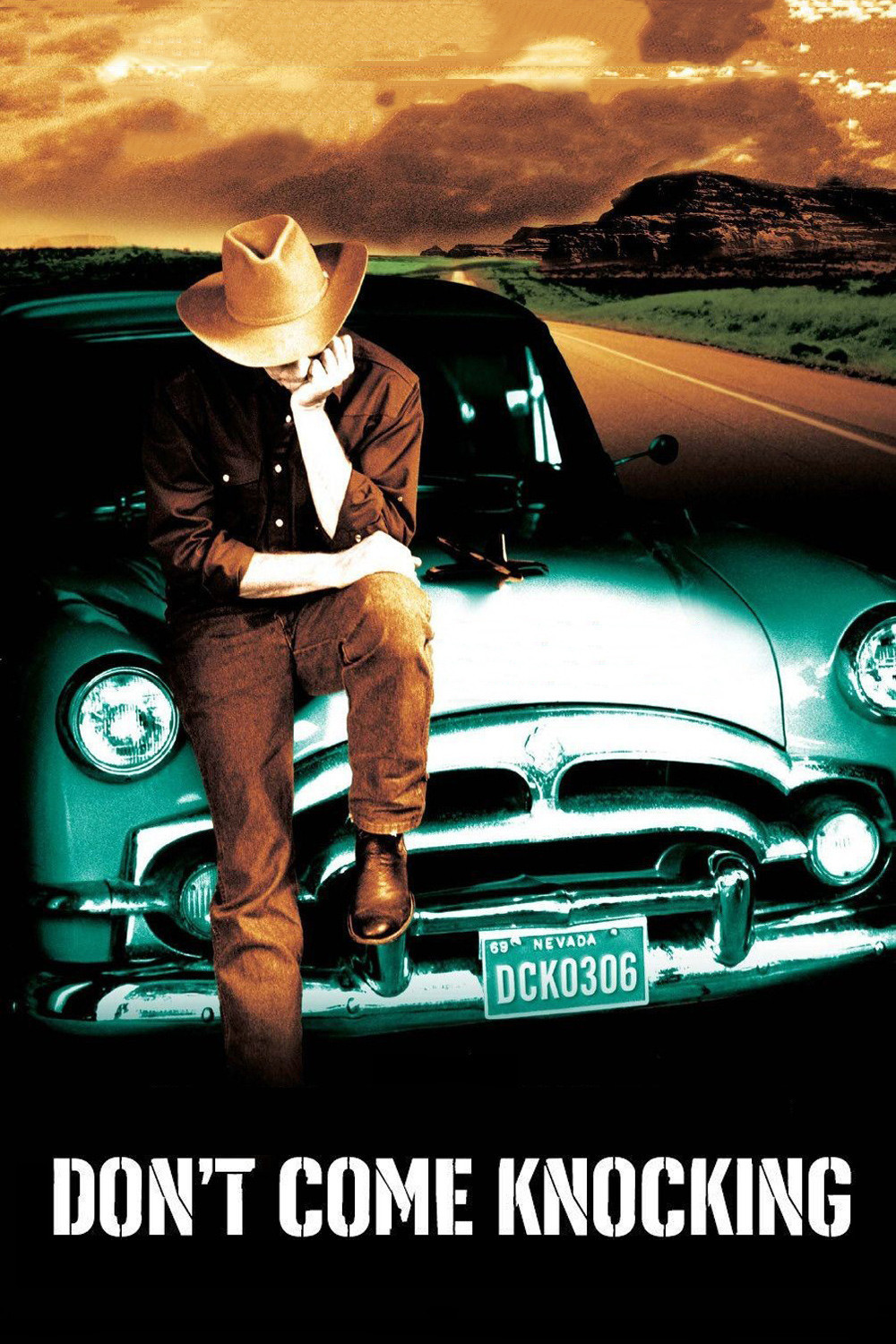

But, no. It’s supposed to be a real Western, starring Howard Spence (Sam Shepard), a once-great Western star, now disappearing into cocaine and booze after a lifetime of scandal. “Don’t Come Knocking” was written by Shepard and directed by Wim Wenders; they wrote and directed the great “Paris, Texas” (1984). What they should know is that once-great stars do not disappear into bargain basement versions of their earlier work, but move laterally into independent films that use their presence as an icon. That’s what’s happening here: Shepard may be playing a pathetic has-been, but what he really brings is an actor and playwright who embodies Western myth in modern dress. I suppose I have seen all of Shepard’s work on the screen, and have never caught him being less than authentic.

That’s true here, even at times when his Howard Spence is like a little boy who never grew up. Now he simply walks away from the set. He calls the mother he hasn’t seen in 30 years (Eva Maria Saint), and goes to see her in Elko, Nev. He arrives not as if decades have passed, but as if he’s late coming home after school. As mothers will, she pages through the scrapbook she’s kept of her famous son, and we see stories about drugs, divorces, brawls and box office disasters.

She tells him of a son he has in Butte, Mont. He goes to Butte in search of this unknown child, and finds the boy’s mother working as a waitress. She is Doreen (Jessica Lange), still attractive, amused that this joke should have walked back into her life. He follows her into a bar. “If you’re looking for your son,” she says, “that’s him, right there in front of you.”

The son is Earl (Gabriel Mann), very good as an uncertain and mannered young would-be folk singer with a lot of resentment against his father. His girlfriend Amber (Fairuza Balk), like a young of young women who affect a ferocious Goth look, is timid and affectionate underneath. Howard realizes he is being followed by another young woman. This is Sky (Sarah Polley), his daughter by yet another woman, whose ashes she is carrying in an urn.

These people move in intersecting orbits through Butte, a city that seems to have essentially no traffic, and no residents not in the movie except for a few tavern extras and restaurant customers. Consider a scene where the enraged Earl throws all of his possessions out the window of his second-story apartment and into the street. His stuff remains there, undisturbed, for days. No complaints from the neighbors. No cops. Howard Spence spends a night on the sofa, sleeping, thinking and smoking. It’s a lovely scene. After Howard’s meditative night, he comes to a peace of sorts with his son and daughter, and they with each other. As this process takes place, they all seem outlined against their own mental horizons, as archetypes who represent something: A cowboy’s last hurrah, a rebellious son’s acceptance of his father, a lost daughter’s opportunity to fabricate a funeral for her mother by going in search of the mourners.

The characters stand for so much, it’s all they can do to bear the weight. Tim Roth is more realistic, as a tracer for the insurance company that holds a bond on the movie. His job is to track down Howard Spence and bring him back alive. This he does with such dispatch that he hardly seems aware he is interrupting a family drama.

The cinematography by Franz Lustig looks wonderful from beginning to end, but no shot equals one where we see Howard Spence sitting in a lonely hotel room window overlooking a desolate city street. Surely when they framed this shot Wenders, Lustig and Shepard were thinking of Edward Hopper crossed with “Main Line on Main Street,” the famous photograph by O. Winston Link. The cinematography evokes a romantic and elegiac mood, within which the peculiarities of the characters may seem sillier than was intended.

“Don’t Come Knocking” finally doesn’t work for me, because instead of embodying its themes it seems to be regarding them from outside, with awe, as if it is the high school production of itself. The supporting characters are all genuine enough, but the central role of Howard Spence is a problem. He needs to be more heroic or more pathetic, I’m not sure which. His life seems to be lived outside his experience, as if someone else made all those headlines in his mother’s scrapbook. “Nothing that happened back then happened,” he says, summing up his life with one line that puts its finger directly on the character’s biggest problem.