“Mama take these guns away from me; I can’t shoot them any more.” That was Bob Dylan in 1973, breathing newish life into an origin-untraceable piece of Americana Mythos, that of the marshal who hangs up his firearms for whatever reason.

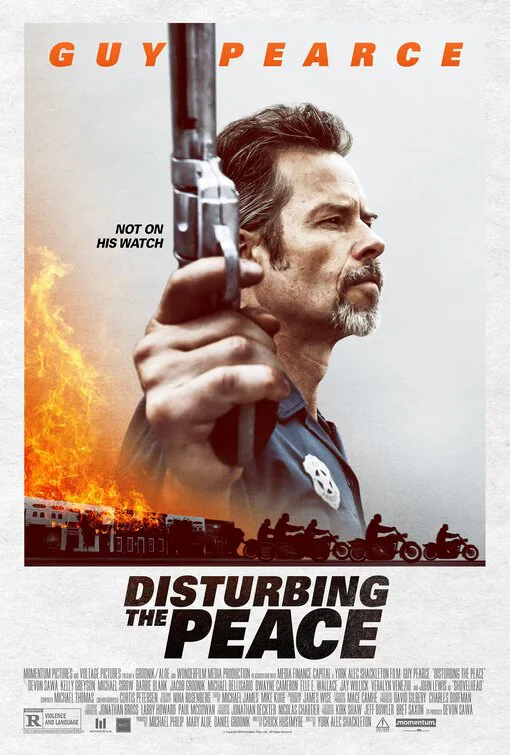

In “Disturbing the Peace,” we see, in desaturated color—so we know it’s a flashback—why Guy Pearce’s Marshall Jim Dillon has hung up his piece. The goldurn thing went ant took out his partner when it ought have been killin’ a bad guy. Could happen to anyone, really, but Jim took it hard, left the Texas Rangers, and came to the town of Horse Cave, a quiet little burg where the local diner owner is also the daughter of the local preacher, and the God-fearing local Farmer’s Bank also gets the armored-car taken from a local God-fearing casino.

Early on, said diner is visited by a couple of bikers. They’re not wearing helmets, so you know they’re bad news. One of them picks a fight with its owner, played by Kelly Greyson, and they do some indifferent martial-arts kicking before Marshall Jim breaks it up. Something’s fishy, he thinks, and he’s right. The two bikers are advance men for a team led by Scorpio (Devon Sawa), whose un-merry band intend to rob the bank and take general revenge on a town that Scorpio hates, for reasons that remain unclear despite the fact that Scorpio can’t keep his mouth shut—he’s the kind of criminal who will hold forth on an armored car driver’s “abject failure” before actually unloading the contents of the armored car. This is the sort of thing that will, of course, trip him up.

Directed by York Alec Shackleton from a script by Chuck Hustmyre, “Disturbing the Peace” is a dull-as-dishwater, paint-by-numbers cinematic hiccup with no discernible reason for being. Sawa, going from strength to strength in this stretch of the 21st century (“The Fanatic,” “Jarhead: Law of Return,” and this in less than eight months) now looks like what you expected Anthony Michael Hall to look like as an adult, as opposed to how the actual Anthony Michael Hall looks as an adult. So that’s interesting. So, too, is the unusually protracted nature of the movie’s standoff. The tension builds to such a boiling point that Marshall Dillon has time to saunter (okay, he backs up against walls and looks carefully around corners for a bit) back to his house to retrieve the revolver he had once retired, and look at it lovingly before holstering it. No hurry here.

There is also the precision-gem-cut acuity of the dialogue, as when Scorpio upbraids one of his henchmen about growing a conscience over killing. “You weren’t so worried about it IN IRAQ, were you?,” offers Scorpio as a moral challenge. “That was war,” protests the henchman. “THIS IS WAR,” Scorpio reasonably responds. Later, when the henchman is in the pokey, Dillon says “I heard him say you were a … Marine.” And the henchman responds “Ex,” and Dillon says “No such thing.”

Occasionally, Shackleton will throw out a random nasty killing as a way, maybe, of demonstrating that he can be as ruthless as S. Craig Zahler, but even in these instances the return is weak. Recently at a football viewing party someone asked me, “How do so many of these bad movies get made, anyway,” and while I had a provisional answer, I did not have a detailed answer. A picture so roundly inconsequential and weak as this only deepens the mystery.