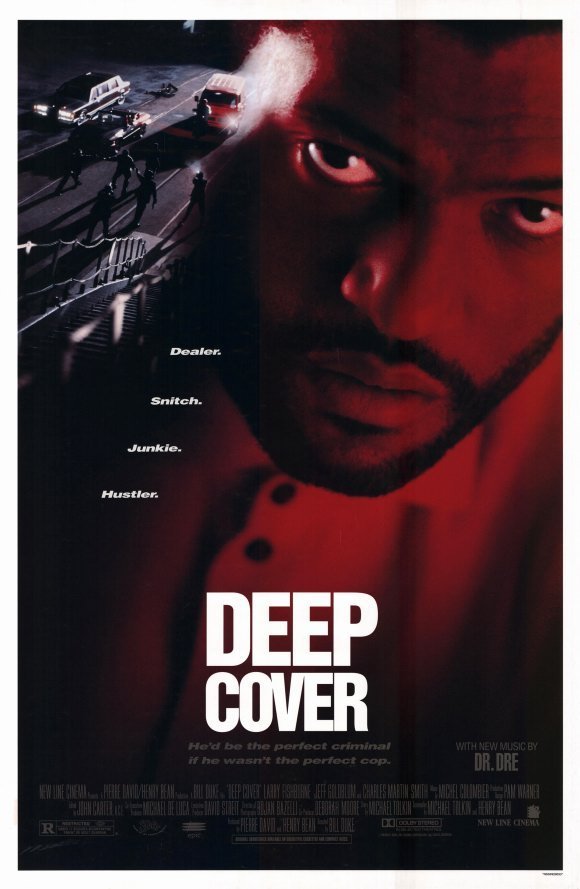

Laurence Fishburne stars, in, surprisingly, his first lead role, although he has been in movies since he appeared in “Apocalypse Now” (1979) as a 15-year-old and had the key role of the father in “Boyz N the Hood” (1991). He plays a cop who is assigned to go undercover and ingratiate himself with an important ring of cocaine dealers. He finds this hard to do; as a child, he witnessed his own father killed while pulling a stickup, and his psychic well-being depends heavily on his self-image as a cop – as a good guy, a straight arrow.

He is talked into taking the assignment by a cold federal agent played by Charles Martin Smith, who overcomes his resistance by quoting from a psychological profile: “You score almost like a criminal. You resent authority and have a rigid moral code, but no underlying system of values. Look at all your rage and repressed violence. Under cover, your faults will become virtues.” Fishburne goes undercover as a street buyer of cocaine. He is able to work his way into the circle of a mid-level drug distributor, played with a nice, off-balance craziness by Jeff Goldblum. And eventually Fishburne infiltrates the highest levels of the organization, which is bringing drugs in from Latin America.

All of that is more or less routine, the stuff of many other movies. What sets “Deep Cover” apart is its sense of good and evil, the way it has the Fishburne character agonize over the moral decisions he has to make. Most drug movies are so casual about their shootings and killings that you’d hardly think it even hurt to get shot. Fishburne, faced with a situation where he might have to kill somebody, is deeply torn, and he suffers agonizingly through the aftermath. He engages in bitter arguments with Smith over the morality of the actions the government wants him to take. And as the child of an alcoholic who was shot while drunk, he doesn’t drink or use drugs, until a crucial turning point in the movie.

“Deep Cover” was directed by Bill Duke, who directed a lot of television before getting his first feature assignment (“A Rage In Harlem” in 1991). He consciously goes back to traditions of 1940s film noir here; he has Fishburne narrate the story much as Fred MacMurray did in “Double Indemnity” (1944) and allows the language of the narration to be poetic and colorful. That’s part of the process elevating the story from the mundane to the mythic.

The screenplay is by Henry Bean and Michael Tolkin. Bean is unknown to me, but Tolkin is having a hot year after directing and writing “The Rapture,” about a woman who moves from promiscuity to deep religious belief, and writing Robert Altman’s “The Player,” about a Hollywood executive whose studio power struggle seems to threaten him more deeply than a murder investigation. Tolkin is clearly interested in characters who do wrong and then have to live with the consequences of their actions. Unlike the countless movie characters whose only goal is to kill their enemies and obtain their desires, the Fishburne character is placed in the middle of moral dilemmas that torture him and then left to figure his own way out.

This fresh material inspires the actors. Fishburne is strong and complex in a role that marks him for more leading work. Goldblum whirls through scenes with wacky dialogue (“Let’s have dinner!” he shouts to a victim during a bloody chase scene. “We’ll have shrimp!”). Victoria Dillard, as a dealer in African art who also launders money, has to make a moral about-face much as the central character in “The Rapture” did. Among the many unexpected aspects of this movie is the way its characters constantly ask themselves what the right course is – and if they can afford to take it.