There must be fewer experiences more wounding to the heart than for a parent to look at a child and fear for its future. In inner-city America, where one in every 21 young men will die of gunshot wounds, and most of them will be shot by other young men, it is not simply a question of whether the child will do well in school, or find a useful career: It is sometimes whether the child will live or die.

Watching her bright young son on the brink of his teenage years, seeing him begin to listen to his troublesome friends instead of to her, the mother in “Boyz N the Hood” decides that it is best for the boy to go live with his father. The father works as a mortgage broker, out of a storefront office. He is smart and angry, a disciplinarian, and he lays down rules for his son. And then, out in the streets of south central Los Angeles, the son learns other rules.

As he grows into his teens, his best friends are half-brothers, one an athlete, the other drifting into drugs and alcohol. They’ve known each other for years – and have steered clear, more or less, of the gangs which operate in the neighborhood. They go their own way. But there is always the possibility that words will lead to insults, that insults will lead to a need to “prove their manhood,” that with guns everywhere, somebody will be shot dead.

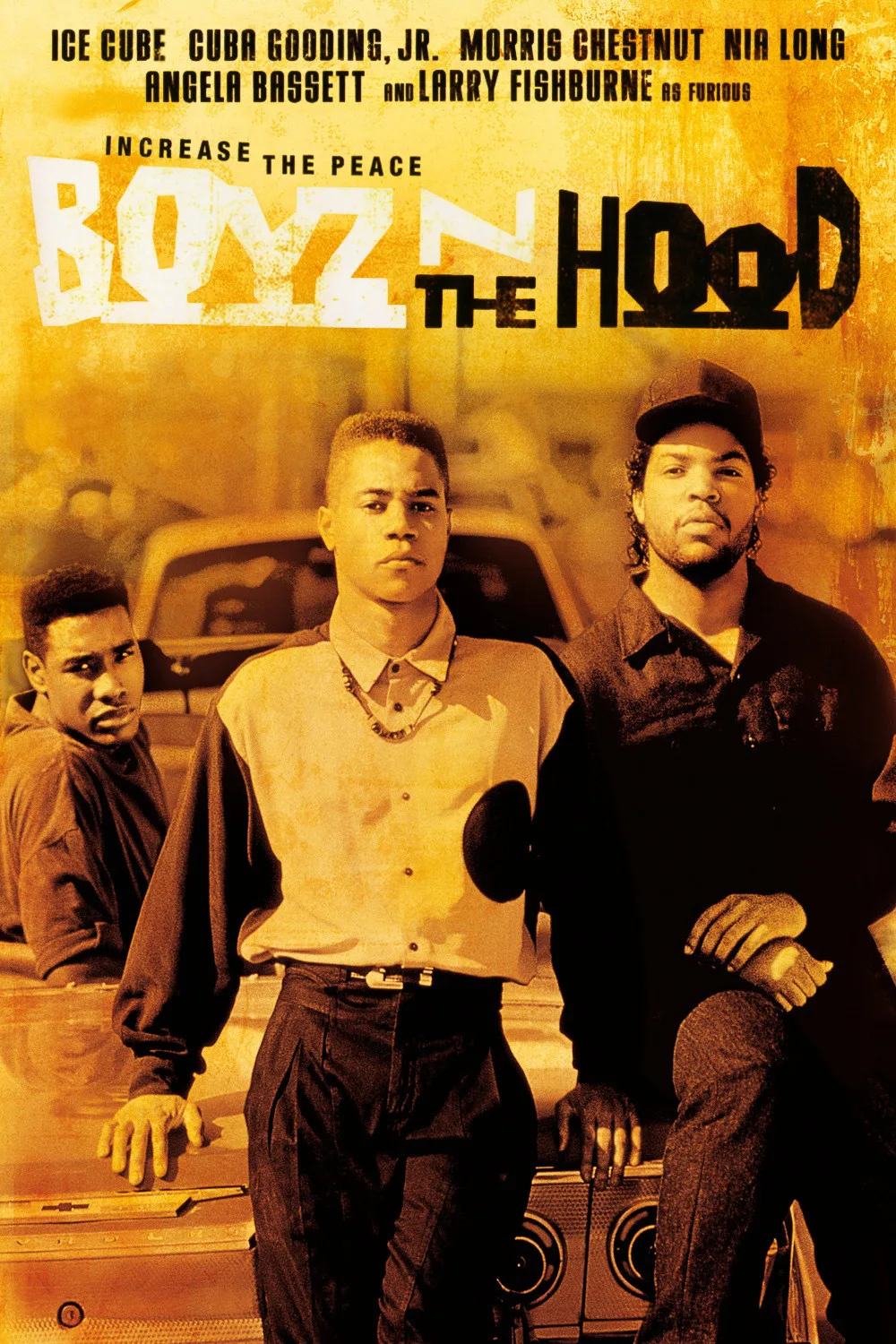

These are the stark choices in John Singleton’s “Boyz N the Hood,” one of the best American films of recent years. The movie is a thoughtful, realistic look at a young man’s coming of age, and also a human drama of rare power – Academy Award material. Singleton is a director who brings together two attributes not always found in the same film: He has a subject, and he has a style. The film is not only important, but also a joy to watch, because his camera is so confident and he wins such natural performances from his actors.

The movie’s hero, who will probably excel in college and in a profession, if he lives to get that far, is an intelligent 17-year-old named Tre Styles (Cuba Gooding Jr.). His father, Furious Styles (Larry Fishburne), grew up in the neighborhood, survived it, and understands it in two different ways: as a place where young men define their territory and support themselves by violence, and as a real estate market in transition – where, when prices and lives there find their bottom, investors will be able to buy cheap and then make money with gentrification.

Furious Styles also knows the dangers for his son – of gangs, of drugs, of the wrong friends. He lays down strict rules, but he cannot be everywhere and see everything. Meanwhile, Singleton paints the individual characters of the neighborhood with the same attention to detail that Spike Lee used in “Do the Right Thing.” He’s particularly perceptive about the Baker family – about the mother (Tyre Ferrell) and her two sons by different fathers, Dough Boy (rap artist Ice Cube) and Ricky (Morris Chestnut). Both live at home, where it is no secret in the family that the mother prefers Ricky.

He’s a gifted athlete who seems headed for a college football scholarship.

Dough Boy is not a bad person, but he is into booze and drugs and will sooner or later find bad trouble. He spends most of his days on the front steps, drinking, plotting, feeding his resentments. They live in a neighborhood where violence is a fact of life, where the searchlights from police helicopters are like the guard lights in a prison camp, where guns are everywhere, where a kid can go down to the corner store and not come home alive. In painting the cops as an occupying force, Singleton is especially hard on one self-hating black cop, who uses his authority to mishandle young black men.

In the course of one summer week or two, all of the strands of Tre’s life come together to be tested: his girlfriend, his relationship with his father, his friendships, and the dangers from the street gangs of the area. Singleton’s screenplay has built well; we feel we know the characters and their motivations, and so we can understand what happens, and why.

A lesser movie might have handled this material in a perfunctory way, painting the characters with broad strokes of good and evil, setting up a confrontation at the end, using a lot of violence and gunfire to reward the good and punish the rest.

Singleton cares too much about his story to kiss it off like that.

Look, for example, at the scene late in the film – the morning after scene – where Dough Boy walks across the street and speaks quietly to Tre; he knows what is likely to happen, and yet wants his friend to escape the trap, to realize his future.

“Boyz N the Hood” has maturity and emotional depth: There are no cheap shots, nothing is thrown in for effect, realism is placed ahead of easy dramatic payoffs, and the audience grows deeply involved. By the end of “Boyz N the Hood,” I realized I had seen not simply a brilliant directorial debut, but an American film of enormous importance.