In one way or another, I have been waiting for the apocalypse all of my life. Most people, I imagine, never think about it, and those who do probably fear it. Not me. I expect to be filled with joy during the final battle between good and evil, while those fearsome horsemen thunder through the sky – because at least then I’ll know for sure that something exists beyond the material universe, and therefore it is possible to escape from death.

These days, I no longer really think of the end of the world in literal terms. I envy the faith of those who do. When I was in parochial school, the notion of Judgment Day filled me with a rush of danger, as I imagined the Lord evaluating billions of lifetimes, and then turning a particularly stern eye on a certain fifth-grader from Urbana, Illinois.

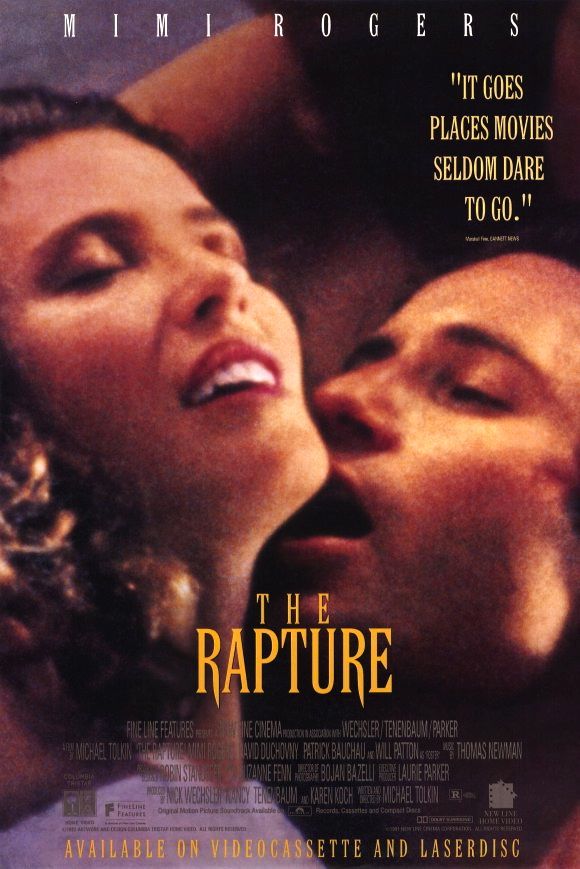

There have been dozens of movies that dealt in one way or another with the afterlife, with death and heaven and hell. But not until Michael Tolkin‘s “The Rapture” has there been a movie to seriously consider what the end of the world might be like, if the biblical prophecies turn out to be literally true. Here is one of the most radical, infuriating, engrossing, challenging movies I’ve ever seen. There are people who love it and many who hate it, but few who can remain on the sidelines. It’s a film with the same ambiguity of the Thomas-Hill hearings; everyone sees the same thing, but nobody can agree on what it means. (“The Rapture” is set to open Nov. 8 at the Water Tower.) Walking into the movie for the first time, last Labor Day at the Telluride Film Festival, I hardly knew what to expect. Certainly not a film that began with casual sex, and ended with a literal depiction of a fundamentalist view of the apocalypse. All I knew of Michael Tolkin, who wrote and directed “The Rapture,” was that he was also the author of The Player, a cold, brilliant novel about a Hollywood studio executive who commits a murder more or less by accident, and then deals with the guilt in passages of excruciating paranoia.

What did we have here? “The Rapture” opens with Mimi Rogers playing Sharon, a woman who works as a phone information operator.

One of dozens of anonymous voices, parceled out in cubicles in a vast room, she conducts impersonal conversations with strangers. In the evenings, accompanied by her lover (Patrick Bauchau), she cruises cocktail lounges, looking for other couples who want to “swing.” They trade mates for sex that is quick, passionate and impersonal.

One day, she overhears co-workers whispering about their dreams. She has had the same disturbing dream, of a pearl suspended in a void. She is drawn into a circle of these people, who have gathered around a young black boy who has the gift of prophecy, and informs them that the world is coming to an end. One night, filled with despair, Sharon calls out in anguish to God, and is born again.

And then the film grows harsh and uncompromising, as she marries, has a daughter, and eventually finds herself standing under the barren desert skies with the child, waiting for the second coming of Jesus.

Everything she does is consistent with the fundamentalist view of how the world will end. There is even an argument for the shocking act she commits, several weeks into her vigil, although of course it is wrong – inspired by the sin of pride, of thinking she knows God’s plans. Watching the film, I wondered how far Tolkin would go. Would the movie lose courage, and end in some kind of sentimental compromise? Or would it go for the literal depiction of the end? Tolkin goes for it. I must be careful not to reveal too much, but let me say that when the bars began to drop from the doors of the jail cells, and fell with a clank to the stone floors, I remembered the nuns describing that final day, when the dead would rise up from the graves, and the prisoners be freed from their cells, all to face a judgment higher than man’s.

If this movie doesn’t leave this earth, I thought to myself, and take me to whatever is on the other shore, I will be angry and disappointed. Can Tolkin be leading me on? He has gone too far to lose heart now.

But Tolkin does not lose heart. And the closing scenes of the movie show Sharon leaving this earth and standing on a shore between Purgatory and Heaven. There, she defies God by asserting something we have all thought from time to time: That he has made us his playthings,that he has asked too much of his creatures. That being free to create any universe, he has made one that stands much in need of improvement.

It has been accurately observed that Tolkin’s special effects in the closing sequences leave something to be desired. True, George Lucas or Ridley Scott could have done more with the River Styx, given several million dollars. But the budget necessary for those special effects would have compromised the film – no one would have risked that kind of money on a movie this daring. Besides, it isn’t how the effects look that’s really important, it’s what they say.

And in “The Rapture,” Tolkin takes Sharon on a terrible journey, from sin through redemption to the ultimate meaning of the rules made by God.

The term “religious film” usually summons up pious banalities, spoken by characters who have not had a thought in their lives. Most movies about the afterlife use the idea of heaven as a plot gimmick, in stories about moony-eyed lovers who find each other because of a mistake in the celestial bookkeeping.

But the next world is not likely to be fuzzy and warm. We live in a terrifying universe, and Christian theology, read literally, makes it more terrifying still: After our allotted decades on earth, during which we pass the time by eating, drinking, smoking, having sex, working, watching TV, going on vacations, becoming sports fans and taking up hobbies, we are suddenly catapulted into a realm where we will spend eternity in either infinite bliss, or infinite misery.

If we lived in full belief and full consciousness of such an eternity, surely life would drive us mad. The risk of damnation would be too great to allow a moment’s relaxation, and indeed some of the saints seem to have been deranged by such fears, their insanity passing for holiness. The great courageous act of Tolkin’s “The Rapture” is to consider such questions in a film that is not overtly “religious” at all. He is not trying to proselytize or convert his viewers, and indeed I imagine some believers will be quite offended by this film. What he is doing, from a secular point of view, is examining the logic of the final judgment as radically and uncompromisingly as he can.

Movies are often so timid. They try so little, and are content with small achievements. “The Rapture” is an imperfect and sometimes enraging film, but it challenges us with the biggest idea it can think of, the notion that our individual human lives do have actual meaning on the plane of the infinite.