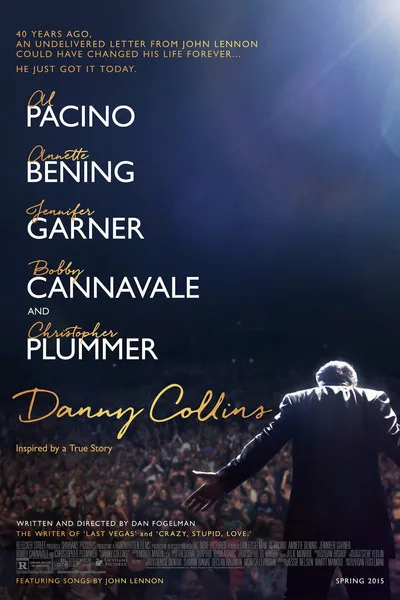

“Danny Collins,” about an old pop star discovering the true meaning of life, is an appealing comedy with an unabashed streak of melodrama, sharp dialogue, and a superb ensemble cast, anchored by a lead performance by Al Pacino in lovable scamp mode. Its excitement comes from watching its leathery, raspy-voiced star play the title character, a Neil Diamond-ish soft rock icon reconnecting with the family he’s neglected for decades while wooing a Hilton manager named Mary Sinclair (Annette Bening) and trying to write something new and good.

If this sounds like a tidy arc, well, it is—but only for Danny, and only at first. Written and directed by first-time feature filmmaker Dan Fogelman (“Crazy Stupid Love,” “Tangled”), the movie is a redemption tale in which a man who has long thought of nothing but money and pleasure experiences a series of emotional shocks, contemplates his life and image, and struggles to become a better man and a deeper artist. From the second we meet Danny, we think of him as a charismatic buffoon, a guy who’d probably be insufferable if he weren’t aware of how little new material he’s written during the last three decades of his career, how few relationships he’s forged of any depth, and how much money he’s blown through (a lot of it went straight up his nose).

When Danny’s manager and best friend Frank (the great Christopher Plummer) gives Danny a birthday gift—a 1971 fan letter from John Lennon inviting him to come to New York and look him and Yoko up—we expect the shakeup to put him on a straight line towards sainthood. After a few sleepless nights, Danny cancels his big-money tour, breaks off his engagement to a younger woman who’s been cheating on him, checks into a suburban New Jersey Hilton, and sets about wooing Mary, working on a vaguely Leonard Cohen-esque confessional song, and reconnecting with his long-estranged son, Tom Donnelly (Bobby Cannavale), a real working-class hero (as per Lennon’s hit) who lives in the suburbs with his pregnant wife Samantha (Jennifer Garner) and their special-needs daughter, Hope (Giselle Eisenberg). The dialogue and story details are often a bit much (did Danny’s granddaughter have to be named Hope, and did the film have to use Lennon’s music as emotional boldface?) and after a while, the film’s meandering rhythm can seem too pleased with itself.

But this is still a hugely effective film, mainly because the path between Danny and redemption proves steeper than he dreamed, and it’s filled with obstructions, some placed by acts of God, others by Danny’s personality and world view (and addictions—not just to drugs and alcohol but to luxury).

And this is what sets “Danny Collins” above other films of its type: its awareness of the gap between the narratives we fantasize for ourselves and the ones we live out. Although we have no cause to doubt the legitimacy of Danny’s existential crisis, Pacino and his director never indulge in special pleading on his behalf; in fact they go the other way, driving home how Danny’s self-improvement regimen is mostly smoke and mirrors. There’s a touch of Royal Tenenbaum to the way he waltzes back into his son’s life and affects a man-of-the-people vibe. It’s possible for an arrogant S.O.B. to be forgiven, but it’s not a matter of flipping a switch.

The entire film could be a feature-length elaboration of the classic confession booth scene in “Salvador,” in which a boozing, whoring, drug-addled man promises to give up all vices in exchange for salvation, then instantly begins carving exemptions for himself. Danny’s resolutions to quit snorting coke, cut back on his drinking, win the love of his son and his family, write great new material, and live a less ostentatiously empty life all seem absurd when you realize how big the challenges are, and how much effort he actually invests in achieving his goals. (“I’m not runnin’ for Pope!” he protests.) Plus, even when Danny’s at his most abashed and thoughtful, he’s still a ludicrous figure, shoehorning a baby grand piano into his hotel room; zipping around in a gull-winged sports car or a tour bus with black leather couches and leopard-and-zebra print pillows; trying to buy his family’s love with day trips and shopping sprees, and strutting through a suburban Hilton in pimp suits, Cuban heeled boots and Robert Evans glasses. (Only Frank can penetrate the shellac of his ego, maybe because he’s the only character old enough to call Danny “Kid.”)

The film invites us to laugh at Danny’s delusions while bearing in mind that it is, on various levels, the story of an addict inching towards recovery while backsliding. Pacino’s vanity-free performance centers the film in reality even when it’s flirting with “Annie”-style wealth porn or edging towards three-hanky-weeper territory. When Danny invites Mary, a witty and enticing but skeptical career woman, to spend the night in his suite, he reassures her that he’s so old there isn’t even a possibility of sex, and when Frank notes that Danny’s new flame is “age appropriate,” Danny self-deprecatingly corrects him: “Not really….baby steps!” The script is more empathetic than withering, mocking the species instead of skewering individuals.

Better yet, not only are most of Danny’s victories small, he seems aware of how small they are, yet grateful to have each one. The character lived much of his adult life at a level where no one could tell him anything (except Frank, and only sometimes). Now, suddenly, has he has to really listen to people and give a damn about their feelings. This proves critically important in his relationship with Tom, a strong and kind but understandably bitter adult son who refuses to give an inch, with good reason. (Cannavale is heroically moving here, playing a troubled but radiantly decent man.) It’s not until fairly late in “Danny Collins” that you realize the redemption arc is a red herring. The film is less about the likelihood of people changing their essence than the necessity of accepting people’s flaws along with their virtues, and making space in your life for anyone who has a good heart and is worth the trouble.