Given the headlines, you might think “Salvador” would be a controversial movie about the United States’ role in Central America.

But it’s actually a throwback to a different kind of picture, to the Hunter S. Thompson story Where the Buffalo Roam, where hard-living journalists hit the road in a showdown between a scoop and an overdose.

The movie has an undercurrent of seriousness, and it is not happy about the chaos that we are helping to subsidize. But basically it’s a character study – a portrait of a couple of burned-out free-lancers trying to keep their heads above water.

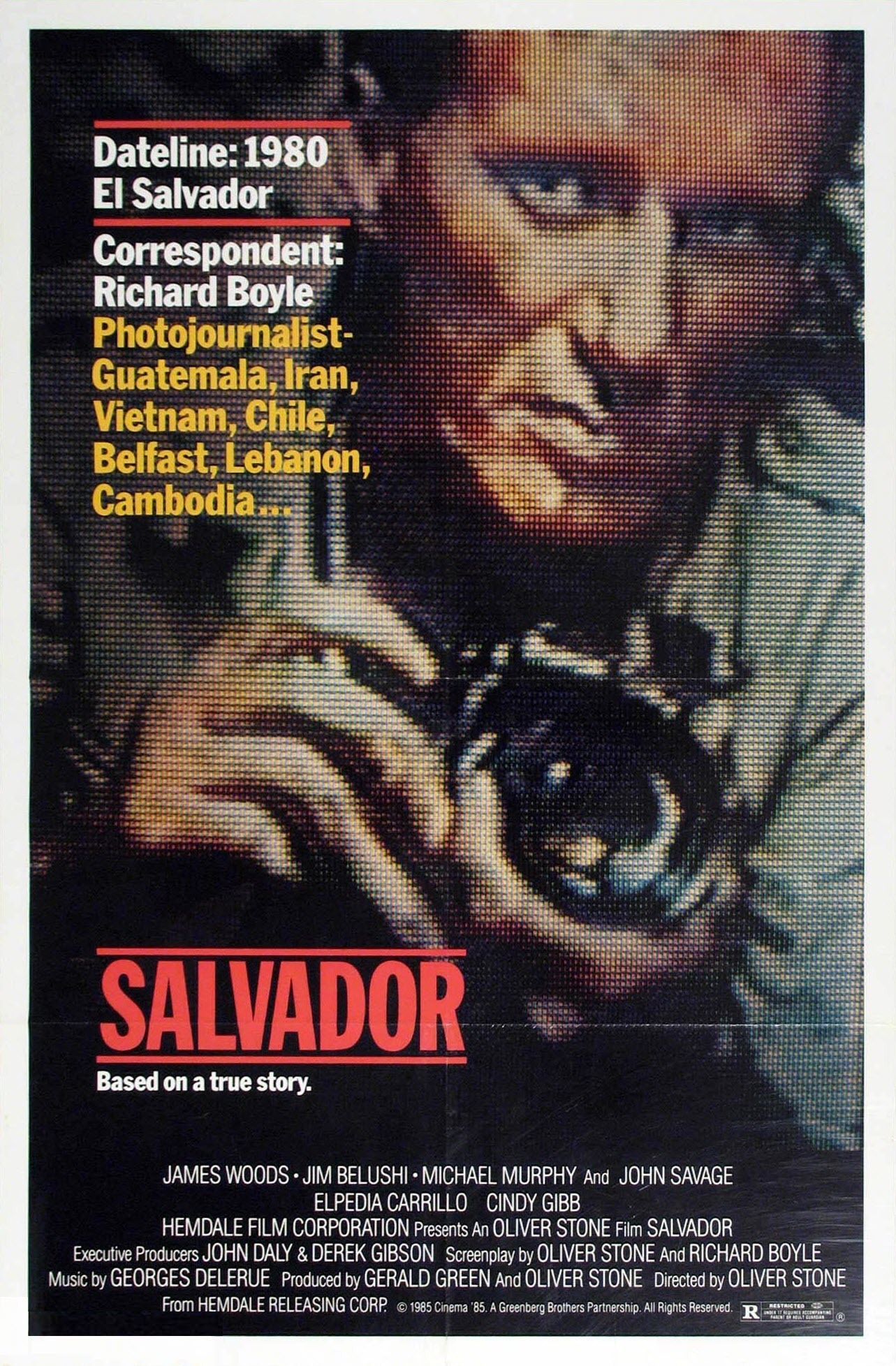

“Salvador” stars James Woods, that master of nervous paranoia, as a foreign correspondent who has hit bottom. He’s drinking, drugging and unemployed, living off past glories. When all hell breaks loose in Central America, he figures it’s a good story since he still has some contacts down there. So he enlists his best friend, a spaced-out disc jockey (James Belushi), and they load up with beer and drive their jalopy through Mexico to where the action is.

The heart of the movie is in their relationship, and I kept being reminded of another Thompson saga, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, where the journalist and his lawyer drove their car through a desert where drug-induced dragons seemed to swoop at them out of the sky.

“Salvador” is a movie about real events as seen through the eyes of characters who have set themselves adrift from reality.

That’s what makes it so interesting.

Once they’re at their destination, Woods and Belushi start looking up Woods’ contacts, who include a neo-fascist general, several bartenders and an old girlfriend. Woods makes a stab at being a correspondent – he’s always on the phone to New York trying to get credentials from a reputable news-gathering agency – while Belushi settles into the local routine of bars and loose women.

A plot of sorts emerges, along with the usual characters we expect in a story like this: the American generals and embassy spokesmen and CIA types. Woods and Belushi hurry off recklessly in all directions, keep finding themselves surrounded by the wrong people and escape with their lives only because Woods is such a con artist.

And he is. This is the sort of role Woods was born to play, with his glibness, his wary eyes and the endless cigarettes. There is an utter cynicism just beneath the surface of his character, the cynicism of a journalist who has traveled so far, seen so much and used so many chemicals that every story is just a new version of how everybody gets screwed.

That’s why there is a special interest in the love affair between Woods and Maria (Elpedia Carrillo). She is a local woman he truly loves, but she lives by a code of Catholicism and respectability – a code that seems constantly in danger of being overwhelmed by events.

The central scene in the movie is possibly the one where Woods goes to confession. He has decided to marry the woman in order to get her out of the country. She insists on a church wedding. And so we get an extraordinary closeup of Woods’ face as he talks with the priest and tries to make some sort of a bargain between Catholic requirements and his total ignorance of conventional morality.

Meanwhile, we meet some of the other people on the scene, including John Savage as a great war photographer and Michael Murphy as the U.S. ambassador, a tortured liberal who speaks of peace and freedom while the CIA goes about its usual business right under his nose.

The subplot involving the Savage character is not very successful.

I can see what they’re doing, trying to set him up as a dedicated photojournalist who will risk his life for a great picture. But when he finally does come to his personal turning point, it’s for a photo even the audience knows isn’t great: a shot of an airplane swooping out of the sky. Without context, it could be any airplane, flying out of any sky.

“Salvador” is long and disjointed and tries to tell too many stories. A scene where Woods debates policy with the U.S. officials sounds tacked on, as if the director and co-writer, Oliver Stone, was afraid of not making his point. But the heart of the movie is fascinating. And the heart consists of Woods and Belushi, two losers set adrift in a world they never made, trying to play games by everybody else’s rules.