There was a time when a sequel to 2000’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” would have been a major cinematic event. After all, Ang Lee’s film not only won four Oscars but is the highest-grossing foreign language film of all time in the United States, making over $120 million stateside and over $200 million worldwide. The fact that the sequel is opening in only a few theaters across the country and that most people will watch it on Netflix says a great deal about the current state of foreign language films more than it should indicate to viewers that this is some sort of straight-to-video, cheapie sequel (and it should be noted that the film made over $20 million theatrically in its first week of release in China). We are rapidly headed to a time when foreign language films and documentaries will only be seen on streaming services like Netflix. In fact, with the highest-grossing live-action foreign language film of 2015 bringing in a paltry $3.6 million (“A La Mala”) and Sony burying last week’s release of Stephen Chow’s “The Mermaid,” it feels like we may be there already.

All of this is designed to explain why “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Sword of Destiny” has been shuffled off to Netflix as unceremoniously as “The Ridiculous Six” (there were no advance press screenings and rumors of canceled advance public screenings). Harvey Weinstein and those at his company know that Netflix is actually the best way to get a film like this to a mass audience. More people will see it this way than ever would with an arthouse and DVD release as it’s now on the front page of the service more and more people use to watch film every single day. But it’s both a blessing and a curse. While it will reach a bigger audience, many cinephiles wrote it off before even seeing it because of the way it’s being delivered to viewers. While it’s not the breakthrough film that will change the way we appreciate Netflix premieres—and, trust me, that day will inevitably come—it is a step in the right direction, a well-made, confident piece of entertainment that lacks the poetry and nuance of the first film and gets less interesting as its narrative thinness is revealed but never feels like something that’s being phoned in to make a quick buck.

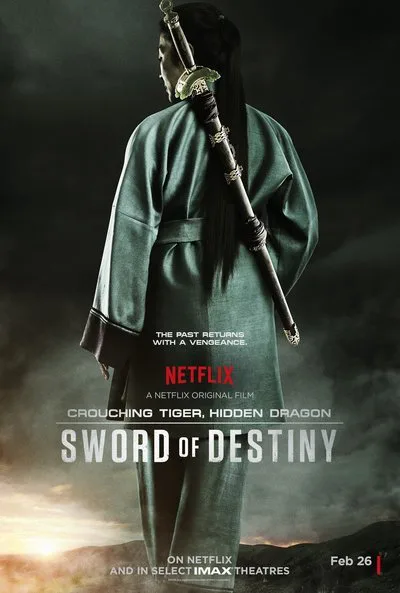

Working from a book in the same series as and by the same author of the original called “Iron Knight, Silver Vase,” Yuen Woo-ping’s film picks up twenty years after the last film. Yu Shu Lien (the great Michelle Yeoh) learns that a warlord named Hades Dai (Jason Scott Lee) has been leaving bodies in his wake as he seeks a legendary sword, the Green Destiny, which is being held by Shu Lien. She is forced to call in her former Iron Way colleagues, including Silent Wolf (Donnie Yen), a former lover of Shu Lien’s who she thought dead. That romantic entanglement is balanced by a younger one between Wei-fan (Harry Shum Jr.) and Snow Vase (Natasha Liu Bordizzo). Wei-fan tries to break into Shu Lien’s compound to steal the sword but is captured by Snow Vase, who is training with Shu Lien.

Writer John Fusco (TV’s “Marco Polo”) may not have been the right man for this particular job. Written and performed in English, the script lacks the wonder and sense of history that the first film carried, too often feeling like a series of poor excuses to get us from one fight scene to another. While the production design by Grant Major (“The Lord of the Rings”), Yeoh’s timeless charisma, and the fight choreography carries the film over its first act, when characters start saying things like “We drink to remember and it seems you drink to forget,” the cheap screenwriting starts to drag the film down. It’s around this point that you also realize that Dai isn’t much of a villain and that the newcomers are a little dull.

And yet Yuen’s sense of scope and skill with fluid fight direction and framing holds the piece together more than a typical, way-too-late sequel. Of course, Yuen was the fight choreographer not just on the original film but for “The Matrix,” “Kill Bill,” “Kung Fu Hustle,” and many more (and directed the “Iron Monkey” movies, among others). He knows how to handle the fluid, balletic combat sequences, including a great multi-character melee at a tavern and a climactic fight scene, captured well by cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel (“Drive”). There’s an undeniable bit of cultural disconnect through “Sword of Destiny”—English language awkwardness, the fact that it looks like it was shot in New Zealand (which it was)—that will be enough for some hardcore martial arts fans to dismiss it entirely. It’s also easy to believe that there’s a longer, better cut in a vault somewhere (this is Weinstein after all, and, well, “The Grandmaster” happened), but response to “Sword of Destiny” is likely to come down to expectation more than anything else—and awareness that the reason this isn’t in a theater near you is more due to the state of the market than the quality of the film.