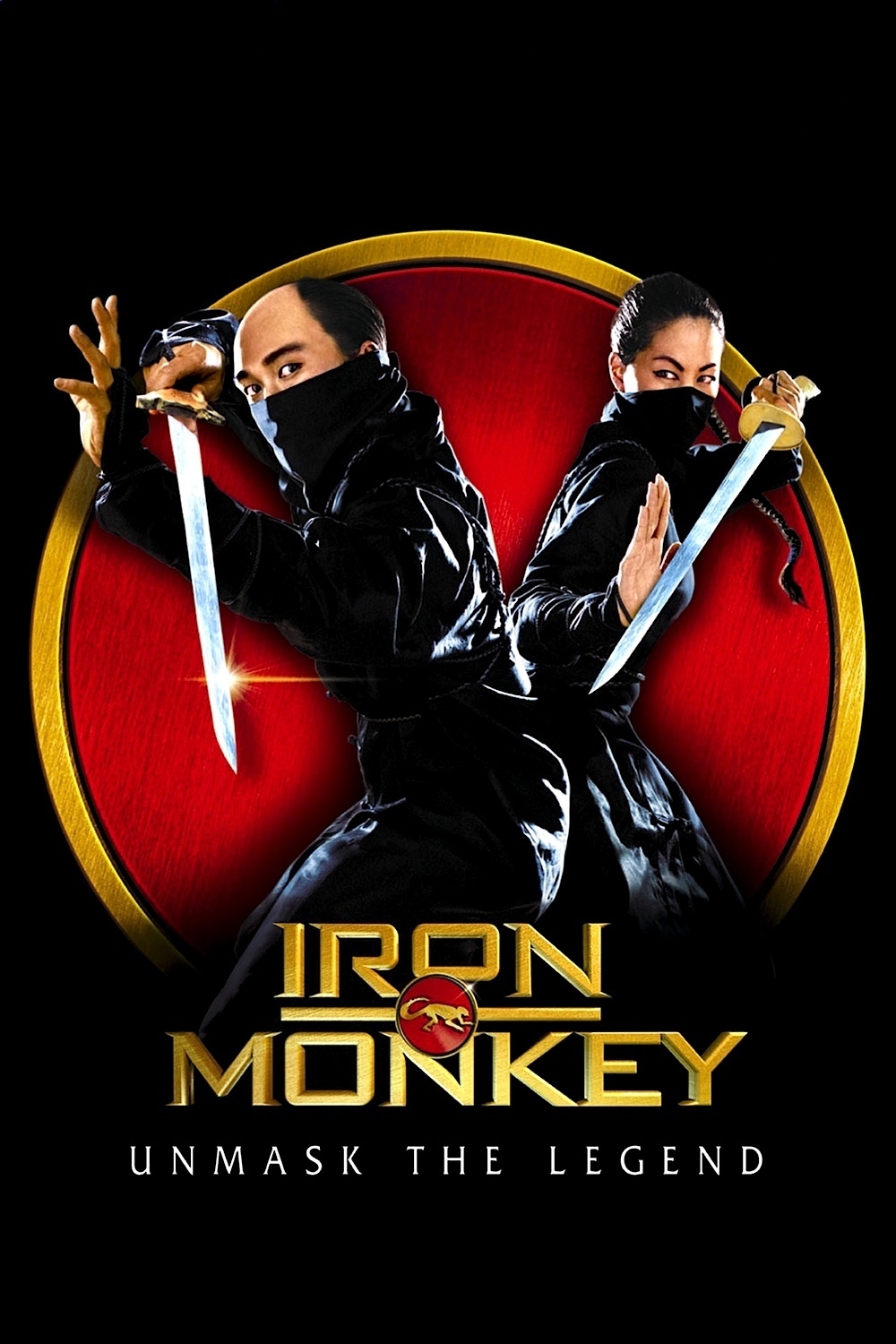

The enormous popularity of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” has inspired Miramax to test the market for other upmarket martial arts movies, and their resident kung-fu fan Quentin Tarantino has gone plunging back into the stacks of classics to “present” a beautifully restored version of “Iron Monkey.” This 1993 film, produced by the action master Tsui Hark, is seen in all its 35mm glory.

The film includes a young version of Wong Fei-hong, whose adult exploits were chronicled in “The Legend of Drunken Master,” a 1994 Jackie Chan film released in 2000 by Miramax’s Dimension division. He was a 19th century folk hero who ranged the Chinese countryside doing, one suspects, very few of the things he is seen doing in this film. (For that matter, in “Iron Monkey” he is played by Tsang Sze-man, a girl.) One of his specialties was “drunken fighting,” in which, by pretending to be drunk, he could loosen himself up enough to be a better fighter.

Here we see 12-year-old Wong Fei-hong traveling with his father, Wong Kei-ying (Donnie Yen) when they are caught in a dragnet set to snare the Iron Monkey, a mysterious Robin Hood figure. Hauled before the provincial governor, Wong Kei-ying is charged with being the Iron Monkey, but then the real Monkey materializes in the court. The governor tells Wong Kei-ying his son will be held captive until he captures the Iron Monkey. Since such a stand-off would have the movie’s two heroes fighting each other, obviously unacceptable, we see young Wong Fei-hong escaping, which frees his father to partner with the Iron Monkey, who is actually Dr. Yang (Yu Rong-guong), a free-lance idealist who fights for the poor against the rich. They find a common enemy in an evil monk.

The story is essentially a clothesline for a series of spectacular action scenes, culminating, as “Drunken Master” did, with one involving fire. This one is pretty spectacular, as the fighters balance on tall wooden poles over an inferno, battering each other with blazing battering rams while leaping from one precarious perch to another. At one point the two allies are balanced one on top of the other on one shaky pole, and at another point they’re balanced on either end of a shaky horizontal pole (this scene may have inspired a similar predicament involving ladders in the recent “The Musketeer“; Western movies are stealing martial arts stunts with shameless abandon).

“Iron Monkey” is a superior example of its genre without transcending it. The Jackie Chan movie benefitted from our knowledge that Chan does most of his own stunts, and “Crouching Tiger” was not simply action scenes but also a poetic story, told with great visual beauty. This movie is great-looking, slick and highly professional, but stops at that. Donnie Yen has great moves, but how many of them are real? What you can see watching “Iron Monkey” is what martial arts fans have been telling me via e-mail ever since “Crouching Tiger” came out: That its scenes of characters running across rooftops and floating in air were far from original, and had been well-established in movies like this one. The technique of using invisible wires to “fly” the characters is not new (on the Web, in fact, it has a name: “wire-fu”). The reason “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” is a better movie is not in the technology but in the art; it incorporates the stunt and action techniques but is not satisfied with them, and aims higher, while a film like “Iron Monkey” is basically aimed at audiences who want elaborate fight sequences and fidget at the dialogue in between. It’s for the fans, not the crossover audience.