“Crimes of the Heart” is that most delicate of undertakings: a comedy about serious matters. It exists somewhere between parody and melodrama, between the tragic and the goofy. There are moments when the movie doesn’t seem to know where it’s going, but for once that’s a good thing because the uncertainty almost always ends with some kind of a delightful, weird surprise.

The film is based on Beth Henley’s play about the intrigues, se crets and scandals of three sisters, the MaGraths, who are brought together for a reunion on the occasion of Babe MaGrath’s decision to shoot her husband (Beeson Carroll).

The film takes place mostly in the MaGrath family home, one of those sprawling Southern manses with gazebos and cupolas and lots of staircases and corners where little girls can hide and giggle. Now the girls are grown, but their games continue, and they gossip and confide about infidelities and adulteries, scandals and betrayals. These are no ordinary girls. Their mother got national front-page publicity for hanging herself and the family cat at the same time.

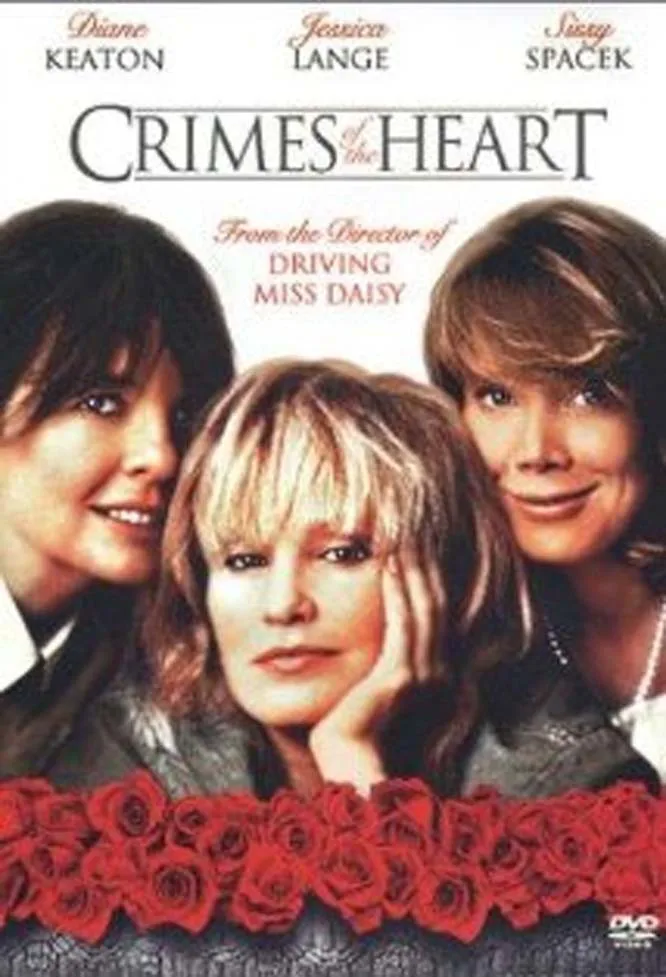

The sisters are played by Diane Keaton, Jessica Lange and Sissy Spacek, and all the time they were making this movie I kept dreading the possibility that it would turn into a series of star turns and one-upmanship. Not a chance. Through some miracle of chemistry, the three actresses seem bound by a history of conspiracy almost from the first shot. They create such an effortless ensemble that I was able to believe they were sisters, despite their physical differences. The supporting cast also seems at home in the long, sick family history: Tess Harper has a couple of wonderful scenes as Chick Boyle, the scandalized cousin who lives next door; Sam Shepard turns up as one of Lange’s many lovers, and David Carpenter has a lot of fun as the family lawyer who has to deal with some steamy photographs.

The MaGrath girls don’t have good luck with their lovers. Babe (Spacek) decided to shoot her husband after he put an end to her affair with a precocious teenage neighbor boy. Lenny (Keaton) met a Tennessee man through one of those lonely hearts clubs but broke it off because of insecurity about a shrunken ovary. Meg (Lange) wants to be a singer and has gone off to Hollywood, where she has had many conquests, no doubt, but none of them too successful, judging by the fact that she returns home on the bus.

“Crimes of the Heart” sets up a certain sprung rhythm in dealing with this material. In some ways, it has more in common with Henley’s work on David Byrne’s “True Stories” than it does with her screenplay for “Nobody's Fool” (1986), the recent film with Rosanna Arquette as a jilted small-town woman who runs away with a visiting stagehand. Henley always seems poised between simple realism and sardonic observation, and her MaGraths are related to the grotesques and eccentrics in “True Stories.” They gather about them all of the props of everyday life – the birthday candles and porch chairs, pickup trucks and chintzy bedrooms – but actually they’re nuttier than fruitcakes.

This is hard material to play. A straightforward family drama would have been nothing, compared with the delicate notes required of Keaton, Lange and Spacek. There is one scene that is a masterpiece.

Lange comes home after a long night’s adultery and is petulant about Old Granddaddy (Hurd Hatfield), who has been ailing. She almost wishes he would go into a coma. Spacek and Keaton exchange an awestruck glance, and then begin to giggle; as luck would have it, they were just about to break the news that Old Granddaddy had just gone into an irreversible coma. Trying to keep straight faces, trying to mourn, they break up into helpless laughter. The scene works as well as the classic Second City skit in which the mourners at a funeral discover that the deceased drowned in a can of pork and beans.

Although Henley’s play won the Pulitzer Prize, which possibly indicates that the judges thought it was about something worthy, I am unable for the life of me to determine a theme in this material, and I doubt if it needs one. The underlying tone of the whole movie is a deep, abiding comic affection, a love for these characters who survive in the middle of a thicket of Southern Gothic cliches and archetypes.

For generations, Southern writers have given us gloomy postbellum family melodramas, filled with secrets too shameful to be revealed except at great length. Now here are the heirs to that tradition – the MaGrath girls – equally beset with sexual and criminal scandal, but unable to keep straight faces.

The secret to presenting this material is, I think, the last thing you might imagine: love and warmth. The director is Bruce Beresford, whose credits include “Tender Mercies,” in which Robert Duvall played an alcoholic country singer. One of Beresford’s strengths as a filmmaker is that he is able to love characters who are very far from perfect, and here he sees the MaGraths just as they are, with no requirement that they stand for anything, make a statement or get better.

That gives Lange, Keaton and Spacek the space to create characters who love one another, but have long since stopped being surprised at anything the others may say or do. If the film had ended with a musical number, the three of them singing “Sisters” while stepping over the bodies of their dead and maimed, I think they actually could have pulled it off.