There are more than 50 sets of twins in David Byrne’s “True Stories,” I learned by studying the press notes, and perhaps we should pause here for a moment to meditate upon that fact. A hundred twins are not going to make or break a movie, and the average audience is not going to notice more than a fraction of them.

Consider the state of mind of the person who decided the film should have 50 sets of twins.

That person undoubtedly is Byrne. What was he thinking of? My hunch is that he was thinking about the movie’s voodoo: the magical things that go on beneath the surface of the work of art, lending it an aura that seeps up into the visible parts. Any movie made by actors and technicians who know that the director has hired 50 sets of twins is going to be a movie made by people who think the director is a very strange man. And that will affect their work. Even the ordinary moments in “True Stories” seem a little odd, as if the actors are trying to humor the weirdo they’re working for.

Byrne says the movie was influenced by true stories he read in the papers, and he has published a book of some of those stories he has collected. They range from the mundane (the happily married couple who have not spoken to one another for 15 years) to the cosmic (the Universal Product Code on grocery items is the advance sign of the coming of the Antichrist).

In “True Stories,” Byrne visits a mythical Texas town named Virgil in which everyone is a little strange and some people are downright unique. Try to imagine Virgil as being populated by everyone who went stir-crazy in Lake Woebegon.

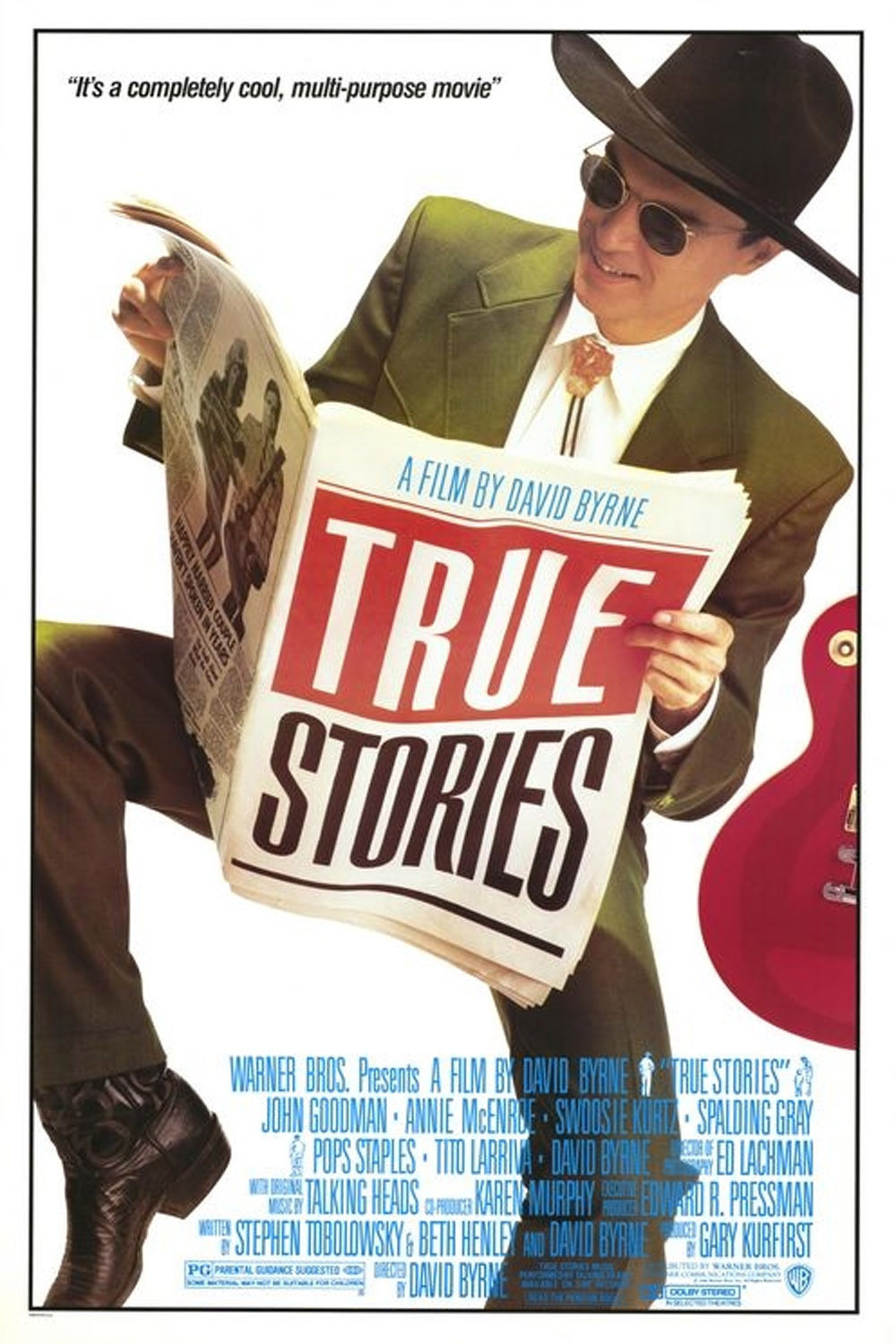

Byrne narrates his film and is the host for the tour of Virgil. He is a thin, quiet, withdrawn figure with a voice so flat that you have to listen to the pauses to figure out when the sentences end. He drives a new red convertible and wears Saturday night cowboy clothes. He takes us to Virgil just as it’s about to celebrate “150 Years of Specialness.” There is no real plot here, just wonderment. We meet a woman too lazy to get out of bed, and a man who advertises for a wife but says she must be prepared to accept his teddy-bear figure. We meet the lying woman, who confides shocking inside scandal on many of the most important events of the last 25 years. She knows because she was there.

We meet civic leaders and marching bands, we visit an old man who casts spells and foretells the future, and we meet a preacher who in one unbroken sentence leaps from the death of Elvis Presley to the fact that we always run out of Kleenex and toilet paper at the same time.

The studio is going nuts trying to figure out how to sell this film. They’re coming down hard on the angle that it has a lot of music by the Talking Heads, the avant-garde rock group that Byrne founded and leads. It does have a lot of music in it, and that will appeal to the audiences that have made “Stop Making Sense,” the Talking Heads concert film a hit.

But this is not a musical. It’s a bold attempt to paint a bizarre American landscape. This movie does what some painters try to do: It recasts ordinary images into strange new shapes. There is hardly a moment in “True Stories” that doesn’t seem everyday to anyone who has grown up in Middle America, and not a moment that doesn’t seem haunted with secrets, evasions, loneliness, depravity or hidden joy – sometimes all at once. This is almost like a science-fiction movie: Everyone on screen looks so normal and behaves so oddly, they could be pod people.

The photography is an important element of the film. The movie was shot by Ed Lachman, who has become a brand name for people interested in offbeat directors. He was the guy who followed Werner Herzog to the slopes of a volcano that was about to erupt to film “La Soufriere,” and he has worked for Wim Wenders, Shirley Clarke, Bernardo Bertolucci, Jean-Luc Godard and Tina Turner.

This time, he finds a new look: His landscapes and city scenes are like those old postcards in which everything seems slightly skewed. His buildings look like parodies of buildings. His people are seen against indoor landscapes of the objects they own – so many objects they seem about to be buried.

And then Byrne orchestrates all of this in the most deadpan way.

If you walk in looking for payoffs, you’re going to be disappointed.

This movie doesn’t start here and go there, and the closest thing it has to a story is the quest of the shy bachelor (John Goodman) for a wife. Will he marry the woman who never leaves her bed? If he does, where will the ceremony take place? It’s the kind of courtship where, when you know the woman well enough, you ask her if she’d like to get out of bed. You see how one thing leads to another?