Particularly flawed in the long shadow of FX’s brilliant “The People vs OJ Simpson,” Rick Famuyiwa’s “Confirmation,” premiering on HBO tonight, has to be considered a notable disappointment. And yet it’s not overtly “bad,” per se. It’s one of those movies that’s easy to describe as “fine.” The performances are fine (and some rise above that description). The production values are fine. The storytelling is fine. The direction? Fine, although you’d never know as vibrant a filmmaker as Famuyiwa was behind the camera. The problem with all that “fine”? The story of Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill deserves more than fine. This is a fascinating political chapter with deep issues of race, gender and power to examine, but the production of “Confirmation” is satisfied with a superficial, then-this-happened approach to storytelling. If you’re old enough to remember the uniqueness of an international story that involved pubic hair on Coke cans, you really know everything “Confirmation” has to tell you.

With opening credits that remind one of the Bork Supreme Court nomination that failed under Reagan, “Confirmation” leads quickly into the selection by President George H.W. Bush of Clarence Thomas (Wendell Pierce) to fill the seat vacated by Thurgood Marshall in 1991. It looks likely that Thomas will be confirmed, especially after relatively successful meetings of the Senate Judiciary Committee, led by Joe Biden (Greg Kinnear). As the committee’s staff members are further investigating Thomas’ history, Ricki Seidman (Grace Gummer), an aide to Senator Edward Kennedy (Treat Williams), comes upon the story of Anita Hill (Kerry Washington), a former co-worker of Thomas, and she has a story to tell. In a rapid series of events (and I did forget how quickly it all unfolded), we were all watching testimony about Long Dong Silver and what Thomas called a “high-tech lynching” on national television. How differently did the confirmation unfold because it was about an African-American man being questioned and an African-American woman not being taken seriously in front of a panel of white men? While this should clearly be the driving artistic question of “Confirmation,” it’s really only casually discussed in the context of a film too quick to get out the facts instead of asking what they meant to the national conversation.

Instantly, “Confirmation” plays like that particular brand of TV melodrama in which people play real-life figures who seem to have a startling amount of self-awareness about their place in history. Did Anita Hill come forward after pressure related to the women’s rights issues on which Thomas would likely vote on the Supreme Court? It probably came up, but almost certainly not in the “TV movie way” in which it does here. The film is weighed down with conversations that sound stilted and awkward, as if everyone knows they’re in a movie. When writer Susannah Grant pauses for a character beat that feels spontaneous—like Thomas listening to “Onward, Christian Soldiers” before testifying—it stands out against a backdrop that just blurs into blandness.

To be clear, I’m not even saying I disagree with the view of the Thomas/Hill as presented by “Confirmation,” but why recount Alan Simpson’s grotesque promise of “real harassment, not the sexual kind” if you’re not doing it for a purpose? Why bother if you can’t find the nuance and the depth of character in this story? It almost feels like an obligation, like something that has been on an HBO whiteboard for a decade and just ended up being the best idea left.

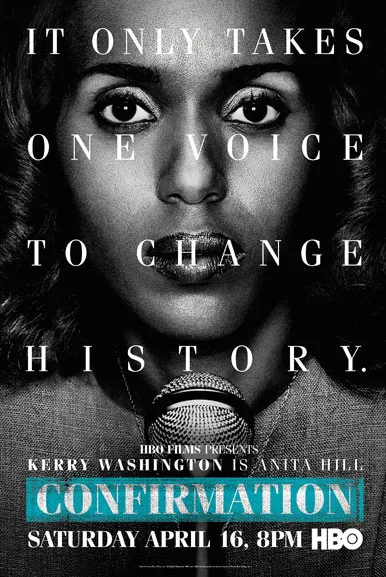

To be fair, the cast does a lot of heavy lifting for Grant and Famuyiwa. Washington deftly balances Hill’s pride with her fear over coming forward, and eventually tapping into her determination. Once she decided she had to say something, she wouldn’t be stopped. Pierce gives a very interesting performance in that he never undermines Thomas’ stance. There’s no shameful look of recognition that maybe he did something wrong, creating an interesting dynamic in that both leads think they’re in the right. Jeffrey Wright, as Charles Ogletree (Hill’s lead attorney), and Bill Irwin as John Danforth, Thomas’ friend and loudest supporter, remind viewers how much these two talented actors can do with very little.

Ultimately, until its fascinating closing credits—which draws the line from the Hill testimony to white men in government being replaced by women (which finally captures the film’s tagline of “It only takes one voice to change history”)—“Confirmation” is pure text. There’s no greater context to the story and little subtext to what we’re watching. It is a recounting of events, which is historically important, but, as filmmaking, it’s just fine.