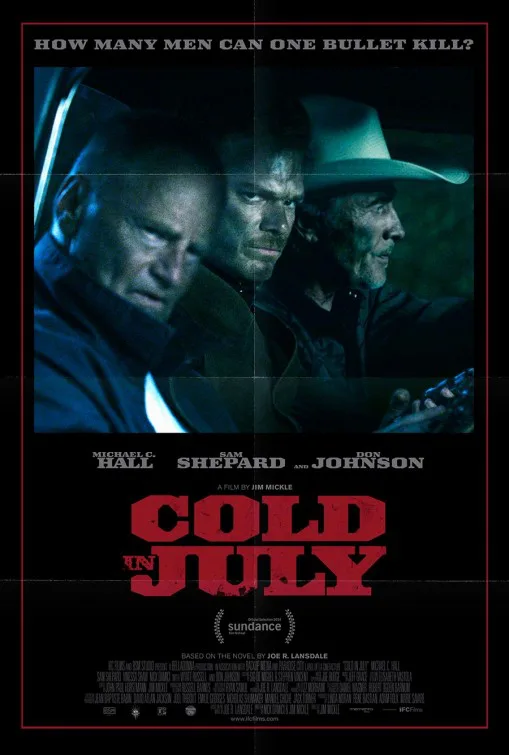

“Cold in July,” a pulpy, Texas-set thriller based on hard-boiled horror/thriller author Joe Lansdale’s novel, fails to capture the discomfiting qualities that make it a Joe Lansdale story. Readers may know Lansdale as the screenwriter of “Bubba Ho-Tep,” or the writer of the bizzaro Jonah Hex mini-series that inspired the awful “Jonah Hex” film. Being faithfully Lansdale-y is a nigh-impossible trick to pull off. Like many of Lansdale’s stories, “Cold in July” starts off as one thing—a straight-forward revenge drama—and soon mutates into something else entirely: a vigilante/buddy film hybrid. Director Jim Mickle (“Stake Land,” “We Are What We Are“) makes an already difficult job even harder for himself by smothering his adaptation in distracting stylistic flourishes.

Admittedly, there are some thoughtful reasons for Mickle’s confrontationally fussy aesthetic choices. “Cold in July” is about emasculated tough guys that don’t know how they fit in a massive conspiracy involving local Texas police, the Dixie mafia and Don Johnson (Note: Johnson sadly does not play himself). It’s a dark, funny neo-noir about being macho, helpless and Texan that needs to be played as straight as possible in order to accent its inherently seedy, and disturbing content.

“Cold in July” starts simply enough. Family man Richard Dane (Michael C. Hall) wakes up in the middle of the night, and kills an intruder. Distraught, Richard attends the would-be burglar’s funeral, and is confronted by Russel (Sam Shepard), his victim’s father. Russel icily threatens to kill Richard’s young son, sending the family man to the authorities for protection. However, Richard soon discovers that Russel isn’t who he’s been led to believe, and the police aren’t telling him everything. It’s a complicated plot involving a trunkful of snuff films, a defiled corpse, and a flamboyant private detective played by Don Johnson (if this film were in Smell-o-Vision, it’d reek of chicken fried steak, and bodily fluids whenever Johnson appeared onscreen). Basically, this film could only be more palpably sleazy if you rubbed the movie screen with a Vaseline-soaked stripper’s thong.

But right off the bat, Mickle stops viewers from getting too close to his film’s ickiness. I had to rewatch “Cold in July” just to accept that Mickle, a technically accomplished filmmaker, chooses to smother viewers for creative reasons. But the bottom line is: thoughtful smothering is still smothering. For starters, Mickle’s camera never seems to sit still. He’s got perfectly capable actors, but he announces that he doesn’t trust them enough to do their jobs whenever he serially abuses tracking shots, and hyper-aestheticized close-ups to establish mood. Again, this is for a reason. Every action is supposed to look and feel portentous because these characters never really know what’s coming next, or how they’re responsible. Mickle tries to establish a sense of mystery by making even small events, like when Richard eyes a new couch, or makes a fraught phone call, feel potentially massive.

Still, the way Mickle visualizes events is often distracting. Take for example a graveyard-set scene. You don’t need to do much to make this scene unsettling: one man is making another dig up a corpse at gunpoint. But Mickle’s camera is restless, and he uses so many camera set-ups that you just want to scream “Put the camera down! No sudden moves! Back away from the camera, slowly!” I mean, honestly, I get why this scene ends with a shot of two principal characters as seen through their car’s foggy windshield. But can’t we just look at these guys without a prettified obstacle in the way? Yes, we get it, they’re headed to the car. But can’t I just watch the characters approach said vehicle head-on, pretty please?

The film’s retro, John Carpenter-esque synthesizer score, composed by Jeff Grace, further pushes viewers away. Grace’s soundtrack augments the film’s nature as a pulpy time capsule. So yes, it makes sense that we’re confronted with one mullet, one conspicuously clunky cellular telephone, and oodles of tacky decor. This is, as a title card states, a period piece set in “East Texas, 1989,” so people act, and behave a certain way. Furthermore, the Carpenter connection is also theoretically interesting: Richard and Russel jump at shadows, and are seen from a remove because they’re essentially anticipating the appearance of a Michael Myers-esque boogieman. I won’t tell you what’s looming over them, but once you know what shady business Richard and Russel are unwittingly involved in, you’ll instantly see it as a dated moral panic (because nothing dates a period more than its greatest public fears).

Again, pushing me away for good reasons is still pushing me away. And treating “Cold in July” like an arty throwback before the fact automatically defangs it. I felt a little safer every time I saw a clunky microwave (how quaint!), or heard a familiar four-note harmony (just like in those other movies!). And that kind of stinks. The essence of Lansdale’s slippery story is onscreen thanks in no small part to Hall, Shepard, and Johnson. But there’s so much wrong with the film’s tone and style that it’s impossible to enjoy what’s right.