Most films require little or no knowledge on the viewer’s part of the filmmaker’s likeness or personal history. But folks who walk into “Closed Curtain” unfamiliar with Iranian director Jafar Panahi and his recent travails are sure to find themselves utterly baffled and confounded. A kind of “film a clef,” the movie (co-credited to Kambozia Partovi) is essentially a psychological self-portrait that depends on the viewer’s knowledge of Panahi’s past work and the strange limbo he has existed in since the Iranian government banned him from working for 20 years—and then tacitly allowed him to go on making films “in secret.”

With films such as “The White Balloon,” “The Circle” and “Crimson Gold” to his credit, Panahi was one of Iran’s most successful and internationally lauded filmmakers when his outspokenness and political activism in the wake of Iran’s contested 2009 presidential election got him in trouble with the government. He was arrested and jailed for a time, and has credited international protests with his eventual release. Nonetheless, he was subsequently put on trial, convicted and given a draconian sentence that included being banned from making films for two decades.

Living under house arrest (and barred from leaving the country) since then, he has used digital cameras to make two films that have been smuggled out of Iran and gained acclaim at film festivals and art houses around the world. In the droll “This Is Not a Film,” he showed himself cooped up in his Tehran apartment and dealing with his de facto imprisonment by reflecting on his past work and continuing to film.

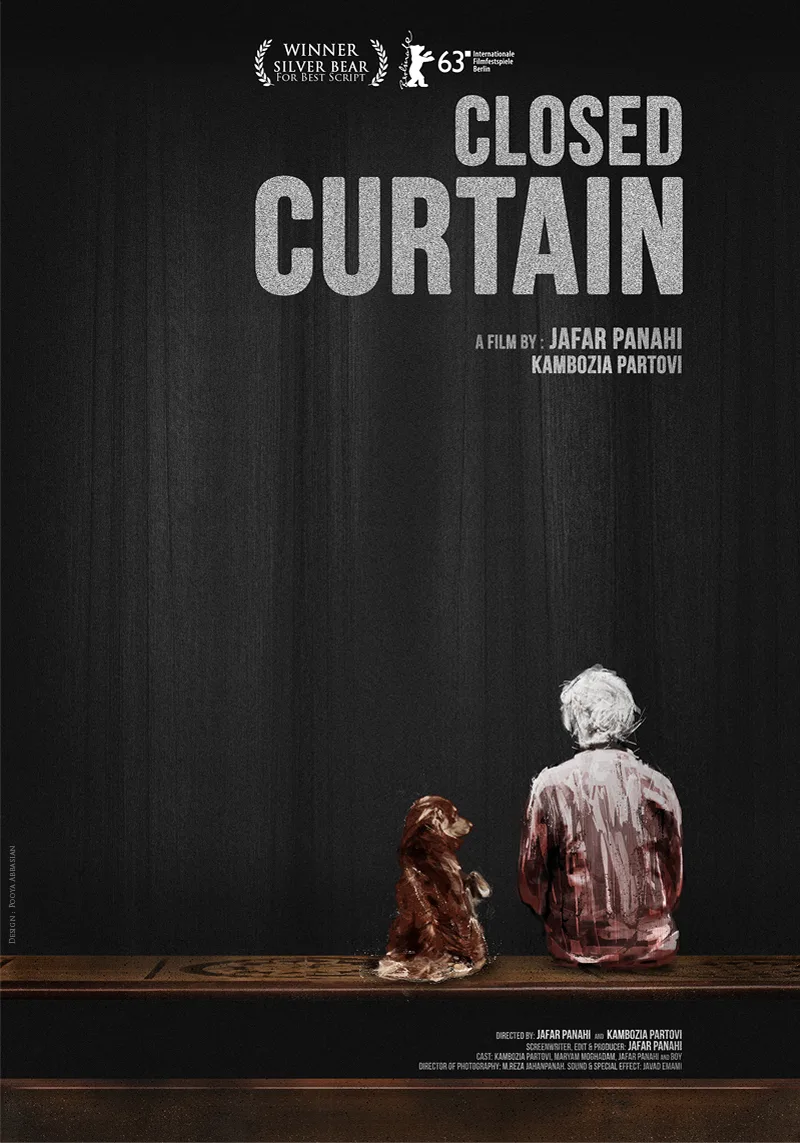

Filmed in Panahi’s Caspian Sea vacation home, “Closed Curtain” at first seems a very different kind of film. A middle-aged writer (Partovi) arrives at a seaside villa bearing luggage, and immediately begins covering the house’s many picture windows with heavy black curtains. One of his bags contains the reason for his secrecy: his dog Boy (played by a personable pooch who gives the best canine performance in recent memory), a pet the man is determined to keep hidden from the authorities who have declared dogs “impure” in Islamic law and therefore subject to confiscation and slaughter.

The solitude of man and dog, though, is short-lived. Going out at night to empty Boy’s litter box, the writer leaves the door open just long enough for a young man and woman to rush inside breathlessly. They say they are a brother and sister who were at a party that was broken up by police who are now pursing them. The writer hears the police as they poke around outside and, thinking the house empty, leave. The young man himself then departs, saying he will get a car and return, and quietly warning the writer that his sister is suicidal.

Something definitely seems amiss with the girl. With her sing-song voice and inexplicable smile, she gets under the writer’s skin from the first moments they are together, invading parts of the house that he doesn’t want her in and making cryptic, insinuating remarks. At first he suspects she may be a police plant, but then sees that she’s too weird for that. After annoying him for a while, she seems to have left the house. Then she reappears and aggressively begins ripping the black curtains from the windows.

At which point, roughly halfway through the film (inevitable spoiler alert here), Panahi himself walks into the frame, and we see that, in addition to baring the windows, the removal of the curtains also reveals Italian and French posters for some of his earlier films. This startling moment recalls a similar one in the middle of Panahi’s “The Mirror” when the little girl playing the film’s main character suddenly declares she’s not acting any more and runs away from the film location, to be followed by other cameras. That “coup de cinema,” though, took us from fiction to something closer to documentary, whereas this one transitions to a kind of subjective surrealism—call it a documentary about the inside of Panahi’s head in recent years.

What follows resembles a narrative broken into shards. Sometimes the focus stays on Panahi as he moves around the house and interacts with visiting neighbors. Sometimes we return to the writer, his dog and the girl. Sometimes the filmmaker seems aware of these “characters,” sometimes not. Occasionally, the tone is gentle and affirming, as when a good-hearted neighbor assures Panahi, “You’ll be able to work again,” while also counseling, “There are more things to life than work.”

Yet there are also darker moments, as when characters are seen walking into the sea to commit suicide, a la Norman Maine in “A Star Is Born” and Roger Wade in “The Long Goodbye.” The girl does this first, yet later reappears. Then we see Panahi do it, but before the action is completed, the film reverses and he moves out of the sea again—one of several instances where we are reminded of the mechanics of filmmaking.

If the dominant mood of “This Is Not a Film” was defiant, the main feeling here is melancholic. In implicitly confessing to suicidal impulses (as his mentor Abbas Kiarostami did in “Taste of Cherry“), Panahi shows how low his confinement has brought him. He still works in order to stay engaged with life and cinema, and this film’s graceful framing, lighting and camera movement testify to his skills as a stylist, yet the movie also raises the question of how many more films he can make about himself and his frustration before hitting a creative wall.

Kiarostami pioneered the Iranian tradition of films about films and filmmakers with movies including “Close-Up” and “Through the Olive Trees.” After venturing into the same territory with “The Mirror,” Panahi’s work grew more political, and politics eventually landed him in a situation where the only ready subjects were a filmmaker (himself) and his work, which has been drastically delimited by the government. He responded with imaginative films that are invigorating and courageous, yet one wishes that he would soon gain the freedom to make other kinds of movies again.