“I am invisible, understand, because people refuse to see me.”

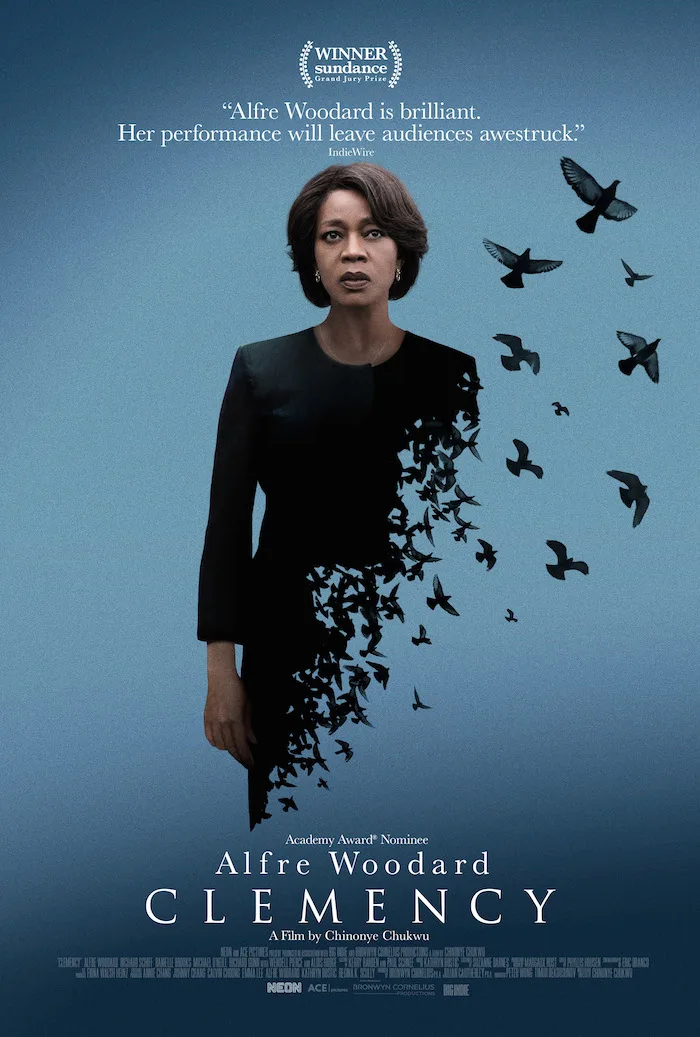

This excerpt from the prologue of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man is mentioned during a seemingly inconsequential moment in Chinonye Chukwu’s sophomore feature effort, “Clemency,” yet its essence reverberates through every frame. 2019 has been filled with films about wrongly incarcerated men, from Destin Daniel Cretton’s stirring fact-based drama, “Just Mercy,” to Terrence Malick’s poetic meditation on righteous sacrifice, “A Hidden Life,” but none have gripped me quite like Chukwu’s masterwork. Though it deservedly earned the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, this picture appears to have evaporated from voters’ memories, which is a crime since its leading lady, Alfre Woodard, is more deserving of Oscar contention than the majority of nominees selected by SAG and the Golden Globes. In many ways, “Clemency” makes a fitting double bill with Ava DuVernay’s equally wrenching Netflix miniseries about the Central Park Five, “When They See Us,” a title echoing Ellison’s aforementioned exploration of how our presumptions blind us to one another’s truth.

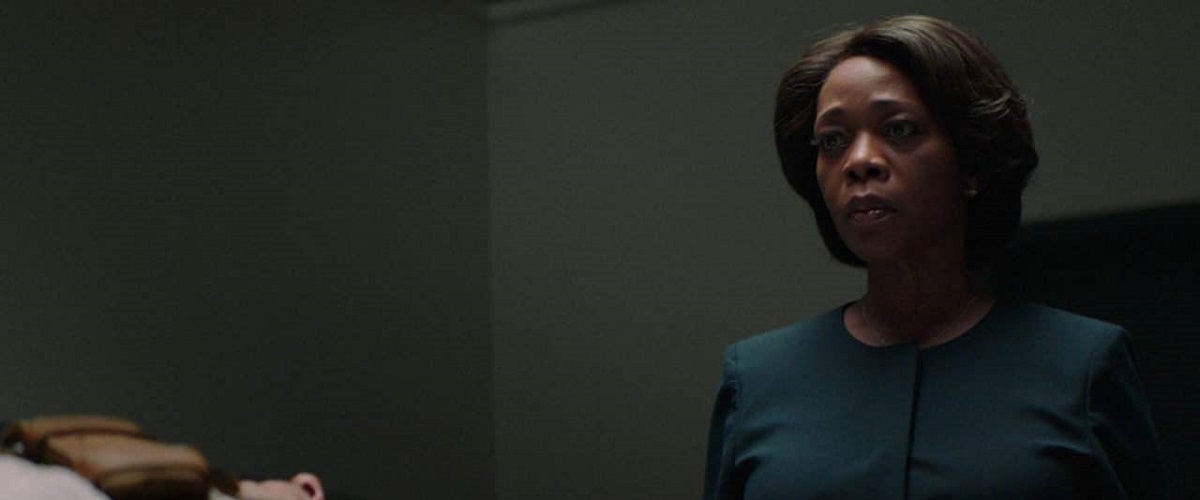

As prison warden Bernadine (Woodard) walks dutifully to work down a corridor during the opening moments of Chukwu’s film, a barred security door framed in the foreground slams shut behind her. It’s one of numerous instances in the film where ace cinematographer Eric Branco makes Bernadine appear as incarcerated as the doomed men she councils. The disconnect that has grown between the warden and her husband, Jonathan (Wendell Pierce), causes him to dub her an empty shell, yet there’s a sense that Bernadine has attempted to shield him from the demons that cause her to bolt upright in bed at night. He couldn’t possibly understand the endurance test she undergoes at work, which is why it makes complete sense that Bernadine may have had an affair with her deputy warden, Thomas (Richard Gunn). The film deftly hints at this without ever making anything explicit, wisely relying on Woodard’s phenomenal ability to convey what cannot be articulated. Watching how she informs Thomas, “I’m having dinner with Jonathan,” followed by a little smile and shrug, tells us everything we need to know about their characters’ past history together.

It’s clear that Bernadine desires to reclaim her wholeness, returning to the bliss she once had with her husband, but as she recoils from his touch, we realize that her soul remains locked in the prison even during her off-hours. “I am alone, and nobody can fix it,” she explains to Jonathan before switching on the television, opting to blot out a surrounding reality ill-equipped to deal with her own. This is a trait she shares with Anthony (the brilliant Aldis Hodge, who recently played another innocent man wrongly accused in “Brian Banks”), a prisoner on death row perpetually perched on pins and needles while awaiting the governor to grant him clemency, a verdict that could potentially arrive just minutes prior to his scheduled execution. To maintain his sanity, Anthony embraces optimism at every turn, covering the walls of his cell with paintings of birds that embody the freedom he believes just might be within his grasp, while calling to mind such classics as “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Birdman of Alcatraz.” He talks over his estranged ex, Evette (Danielle Brooks, in a shattering appearance), hushing her with assurances of forgiveness until she refuses to be silenced, explaining that she isn’t sorry for keeping her distance in order to protect their son.

Whereas Evette chose a life of “barely existing”—her own self-imposed imprisonment—she notes that Anthony’s name will live on for generations. Though “Clemency” is ostensibly a work of fiction, its story was inspired by the 2011 execution of Troy Davis, a black man convicted of killing a police officer in Georgia, a charge that has been repeatedly disputed, considering there is enough evidence to cast significant doubt on his alleged guilt. Instead of following the formula of a procedural, Chukwu finds artfully subtle ways of feeding us information, such as when Anthony’s lawyer, Marty (Richard Schiff), is heard over Bernadine’s car radio, listing the various gaping holes in the case against his client. For much of the picture, Bernadine hovers amidst the proceedings like the Spectre of Death, treating Anthony with a grim formality when all he wants is a hand to hold. The unanswerable questions she directs toward him, such as what food he’d like for his last meal or which family members would be willing to claim his body, render Anthony owl-eyed and utterly speechless. Only when making his final statement—a haunting speech modeled after the transcript of Davis’ last words—does he indirectly address Bernadine by praying, “For those about to take my life, may God have mercy on your souls.”

What follows is one of the most harrowing death scenes ever put on film, and what makes it extraordinary is the fact that we experience it solely through the expressions of Bernadine. As Marty tells Anthony during their final moments together, all any of us ever want is to be seen and heard, and the crowds of protestors lining up daily to loudly condemn his client’s fate provide undeniable proof that news of the injustice has spread throughout the world. Of course, this is little consolation for a prisoner forced to spend the majority of his days in silence and solitude, yet when Anthony is strapped to a crucifix-like chair and given his lethal injection, it’s as if his pain and anguish is injected directly into Bernadine. In a breathtaking three-minute shot on par with the finale of Céline Sciamma’s “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” the camera holds on Bernadine’s face as the primal horror of the procedure she has overseen for years finally sinks in, breaking through her hardened exterior until he flatlines, prompting her own body to go limp. For the first time, she finds herself at a loss for words, just as Anthony was during her feeble attempts at interaction. You can literally spot the moment when her soul appears to have left her body. This is screen acting of a very rare sort, and “Clemency” is a vital emotional powerhouse sorely deserving of being seen.

“Clemency” is now streaming on Hulu, and available for discount rentals on various digital platforms.