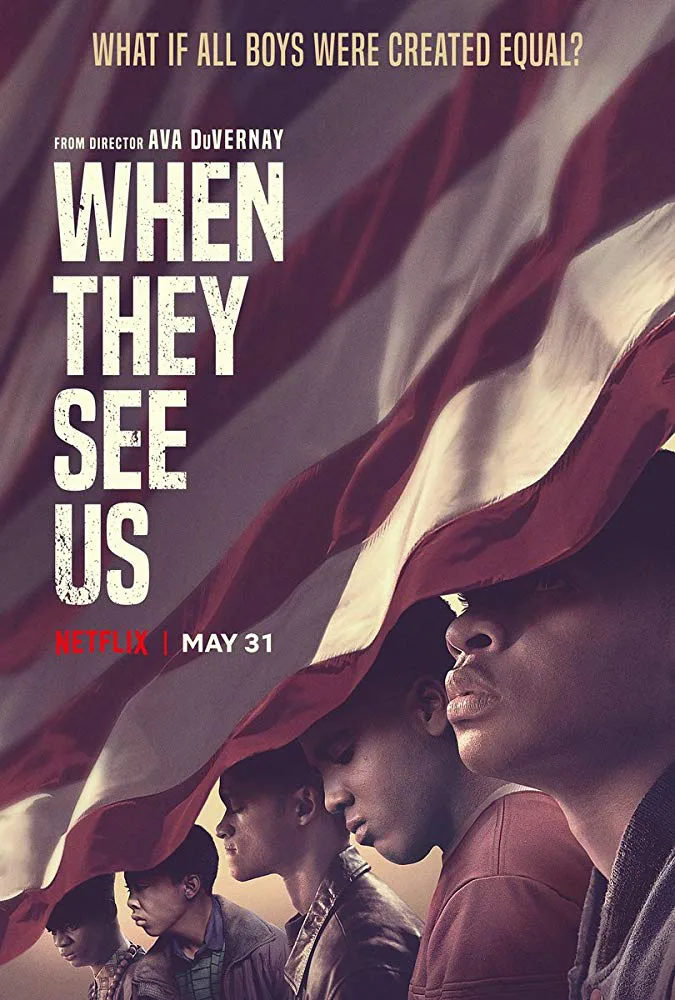

We are republishing this piece on the homepage in allegiance with a critical American movement that upholds Black voices. For a growing resource list with information on where you can donate, connect with activists, learn more about the protests, and find anti-racism reading, click here. “When They See Us” is now streaming on Netflix. #BlackLivesMatter.

The first of many needle drops in Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us” is Special Ed’s hip-hop classic “I Got It Made.” The song is a rather gentle piece of old-school braggadocio, harmless and innocent by the standards of similar records that operate in a boastful vein. The song plays under the opening scene, where young Antron McCray (Caleel Harris) hangs out with his dad, Bobby (Michael Kenneth Williams). As they eat fast food and talk smack, Special Ed flows on the soundtrack about how he sees himself. The rapper’s positive vision appears in stark contrast to the way he and other Black and brown people would be seen by the societal “they” of the title. To them, we are violent thugs, older-looking and more powerful than our age would indicate; uncouth savages “wilding” at will and deserving of less benefit of doubt than our White counterparts.

This is the prism through which the boys forever known as “The Central Park Five” were seen back in 1989 when they were put on trial for a heinous crime they did not commit. Armed with coerced confessions that didn’t even have consistent details of the crime, the press and the prosecutors in New York City convicted Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Jr., Korey Wise and Kevin Richardson, sentencing them to years of prison and all of the after-effects that befall felons who have done time. While the NYPD harassed and terrorized these minors, the actual criminal walked undisturbed through Central Park wearing a shirt drenched in his victim’s blood.

This story has been told before, most notably in Ken and Sarah Burns’ documentary “The Central Park Five.” “When They See Us” uses a four-episode Netflix miniseries format to dramatize and flesh out the details, starting with the events of April 19, 1989, when investment banker Trisha Melli was brutally raped and left for dead in the North Woods of Central Park, and ending in 2002 with the sentences of the five men being vacated after Matias Reyes confessed to the crime. The men appear at the end of the fourth episode and, for a change, the sudden appearance of the real-life subjects doesn’t undermine nor downplay the fine actors who portrayed them.

This is a lot of ground to cover, and DuVernay and her co-writers craft scenes that are horrifying, harrowing, upsetting and infuriating. There are also moments that feel forced or rushed, especially in the fourth episode. But even at its most flawed, “When They See Us” never loses sight of its thesis statement that Black and brown people are presumed guilty at all times, even by White liberals who pretend otherwise. It’s the same thinking that beget “superpredators” and harsher sentences across racial lines; the same thinking that allowed Dylann Roof to get a Whopper after murdering nine people, yet left Michael Brown laying dead in the street for hours. This series is not going to let you forget how the justice system and the press have failed—and continue to fail—people of color.

“When They See Us” doesn’t just hit all the moments that anyone who was around NYC at the time will remember, it also depicts the difficulties faced by men who have come out of the prison system. The rules facing former felons seem designed for maximum failure—they’re so labyrinthine and ridiculous that their descriptions play like pitch-black satire. Additionally, viewers are privy to just how broken and hopeless the formerly incarcerated can be when faced with police pressure. One of the most painful moments in the first episode concerns a father telling his son to lie, to confess to a crime he didn’t commit, simply because he fears the police will kill his kid if he doesn’t comply. Better to go to jail than the morgue.

Each episode has its own most-valuable players either in front of or behind the camera, but the entire series is elevated by the two sets of actors who embody the Central Park Five. Their adolescent counterparts anchor the first two installments while the adult versions support the final two. Support comes from a bevy of familiar faces as prosecutors and parents, from Len Cariou, Felicity Huffman and Vera Farmiga as the former to John Leguizamo, Niecy Nash and Aunjanue Ellis as the latter. As in “If Beale Street Could Talk,” Ellis is perfectly cast as a pious and proud woman. Her Sharone Salaam spars memorably with Nash’s Delores Wise, their friction buoyed by the fact that young Korey Wise (Jharrel Jerome) had accompanied his teenaged best friend Yusef Salaam (Ethan Herisse) to the police station despite not being on the NYPD’s list of suspects.

Episode one focuses on the events before and after the assault on Melli, whom the newspapers referred to as “the Central Park jogger.” Cinematographer and frequent DuVernay collaborator Bradford Young shares this episode’s MVP honors with Michael Kenneth Williams, whose terrifying demands on his son in an interrogation room will have long-lasting consequences. Young shoots this scene and the recreations of the coerced confession videos with a tight, smothering claustrophobia but employs a looser, more chaotic frame for the crowds of teenagers running into Central Park at night. Young lets the characters bask in his darker hues, and incidents of violence are presented in jagged bouts of near-visibility. People are beaten in the park, but none of them pick out any of our protagonists as the culprits.

A lack of evidence to convict the five irks Linda Fairstein (Huffman), a crime novelist who runs the Sex Crimes unit of the NYC District Attorney’s office. Despite having Elizabeth Lederer (Farmiga), the lawyer prosecuting the case, and DA Robert Morgenthau (Cariou) as characters, Fairstein is the most villainous representation of the prosecution. She points out that NYC has been rife with sexual assaults, none of which she appears to pursue as vehemently as this particular case. She’s willing to bend the truth and reshape the pieces to make them fit her narrative. She also accurately predicts that the press will demand blood and a quick turnaround because Melli was the kind of victim who sold papers—young, blonde, White and wealthy. Huffman plays the antagonistic Fairstein quite broadly, and while it’s an effective performance, it’s also “back row of the theater” big. A little of her goes a long way, and some may find her problematic.

The two separate trials that resulted in convictions for the five teenagers occupy episode two. We’re introduced to the defense lawyer team that includes divorce lawyer Blair Underwood and this round’s MVP, Joshua Jackson as Mickey Joseph, a Legal Aid rep who explains the legal process to us while scoring points against Lederer in court. We also see the uneasy coalition between the parents, some of whom can afford better lawyers than others. Another theme in “When They See Us” is how the defendants were victims of, or catalysts for, a series of opportunists. Joseph points out that despite his motley crew of colleagues, this is a major case and a win for any of them would send a career into the stratosphere of fame. Speaking of opportunists, we also see actual footage of a certain fake-news spouting real estate mogul who took out an $85,000 ad in all the New York papers demanding the return of the death penalty specifically for The Central Park Five.

Though the outcome is well-known, this is the most suspenseful of the four parts of “When They See Us.” The courtroom drama benefits from its scenes of testimony, most memorably from Melli (Alexandra Templer) herself. Templer is haunting in her short scene, haltingly speaking about the memory loss and mobility issues that resulted form her attack. The episode later culminates in a powerful array of shots of grieving parents (editor Spencer Averick, who cut two of the four episodes, does his best work here) as the verdicts are read and the young men are dragged away to begin their stints in juvie or, in the case of 16-year-old Wise, Rikers Island. Wise disappears from the series until the last episode, as does the prosecution.

After directing a thriller and a courtroom nail-biter, DuVernay tackles the quiet drama of episode three, the series’ best. She cleverly depicts the transition from the teenaged actors to her adult performers, then leads Antron (Jovan Adepo), Raymond (Freddy Miyares), Yusef (Chris Chalk) and Kevin (Justin Cunningham) through their re-entry into life outside of prison. The script by Robin Swicord and DuVernay is the MVP here, highlighting what DuVernay does best: It points out just how full of pitfalls the system is. The sequence where the correction officer explains the permutations of who a convicted felon (and registered sex offender) can be around is a stunning, absurd primer on how easily it is to be re-incarcerated. It is also nearly impossible to get a job, which will have an unfortunate effect on one of the men by the end of this chapter.

We also witness how difficult it is for the four men to adjust to life In their changed neighborhoods and their new families. Raymond’s father, Raymond Sr. (Leguizamo) has a new wife who doesn’t like his son living in his old room. Antron is shocked to find that his mother has taken his father back after they were deserted during the trial. The men support each other as best they can, with each wondering what happened to Korey. Though the scenes with the adult actors are compelling and well-written, the best moment comes from a story told to young Kevin (Asante Blackk) by his sister, Angie (Kylie Bunbury) when the Richardsons visit him in jail. Angie talks about having something to look forward to, and her story is a funny, romantic distraction (complete with surprise ending) underscored by Frankie Beverly and Maze.

The last chapter of “When They See Us” is its longest, its most harrowing and its most problematic. After only hinting at it, the series unleashes the full horror of both prison life and the assault on Melli. Jharrel Jerome gives a tour-de-force performance as Wise undergoes brutality after brutality. He’s joined in intensity by Niecy Nash, who in solitary-induced flashbacks furiously dismantles the family unit, throwing out Wise’s one point of comfort, his transgender sister. Nash, a DuVernay regular, shows her dramatic versatility in these scenes, which are vastly different from her more comedic work on “Reno 911” and “Claws.”

Taking the advice of a CO in one of the three prisons he’s trapped in, Wise spends as much time as he can in solitary, especially after he’s been assaulted. Inside, he has wild hallucinations and episodes of madness, which admittedly are unsettling but these scenes become a bit redundant. One less sequence might have made the episode feel less rushed once it winds toward the final outcomes for everyone. We spend almost no time on the ensuing lawsuits, though Huffman gets one more chance to be hissable before fadeout.

Once the real rapist decides to confess and the DNA on a sock the DA has always had since the first trial comes back with an exact match, DuVernay stages Melli’s attack. It is restrained but still brutal (I may never fully shake the shot of her body being dragged across the park, leaving a wide trail of blood). And the director makes sure to remind us that while the NYPD was tormenting the Central Park Five, the real culprit was strolling through the park covered in blood and free to commit a few more attacks before being captured.

Taken as a whole, there’s a lot to recommend “When They See Us.” It does as much as it can to recast the gaze on Black and brown people, eliciting empathy and the desire for justice. It demonizes the right people and demands your fury over the events presented. And while the ending does feel rushed, I think I understand why it ends where it does. Sure, we could celebrate in some small fashion that these men were not only exonerated but also won a lawsuit against the city of New York, but that celebration would be cut short by the next travesty of justice. This is a film about how we are seen, but it’s also a reminder that it should not overrule how we see ourselves.

“When They See Us” is now streaming on Netflix.