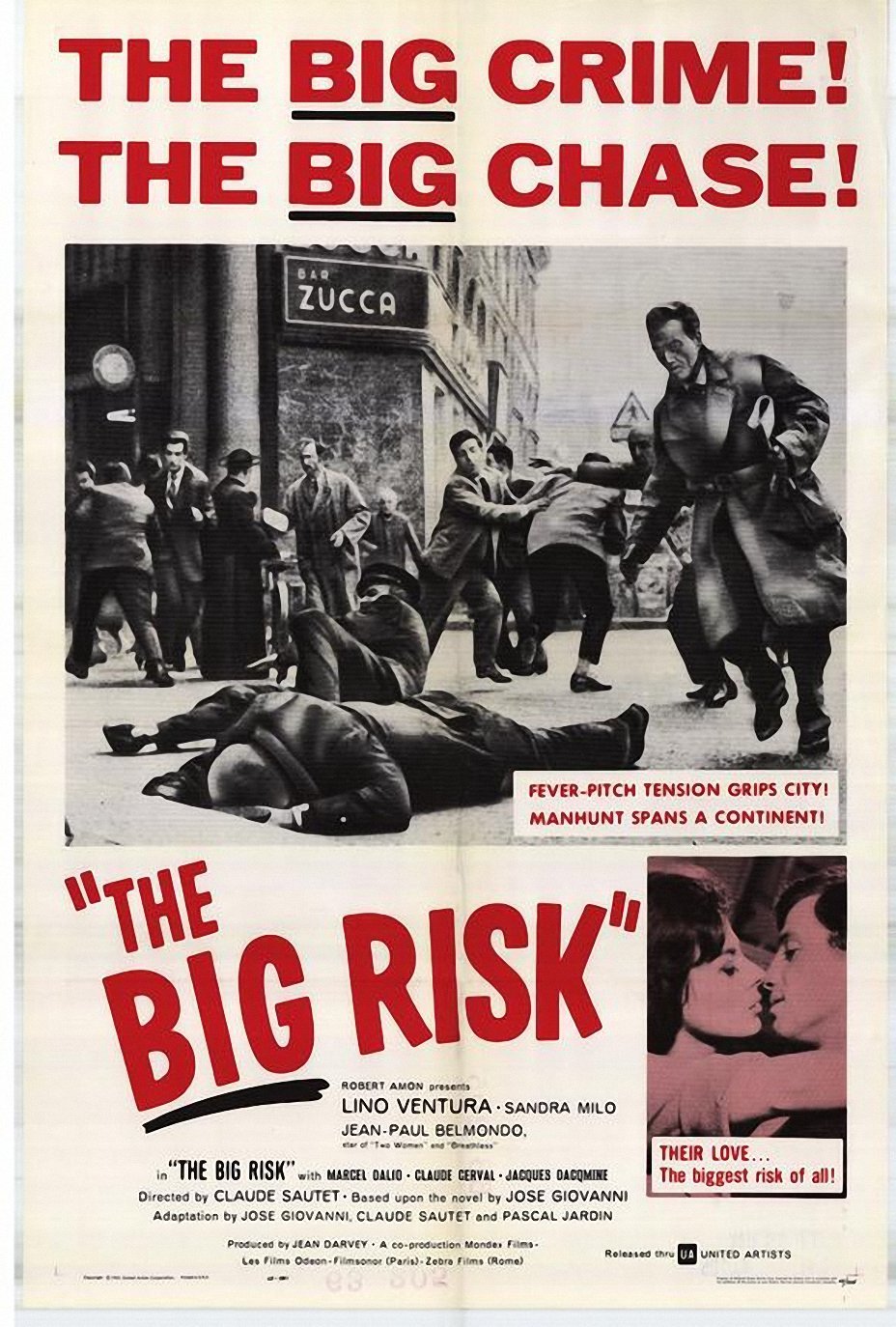

Abel is a convicted killer on the lam from the French, who has lived in Italy long enough to acquire a wife and two sons. He loves his family more than crime. He thinks it is time to return to France. One last job should do it. If he went to more movies, he’d know that calling it your “last job” seems to put the jinx in.

Abel is played by Lino Ventura, with a sad, lived-in face. At the train station in Milan, he meets his wife Therese (Simone France), their sons, and his partner Raymond (Stan Krol). The details of the plan have been carefully prepared: They’ll put the wife and kids on the train to a town just the other side of the French border, then stick up a bank messenger, make a getaway, switch cars, meet up again, and cross into France. Abel has pals in Paris he’s sure will be happy to see him again. He did them a lot of favors.

The snatch-and-grab on a Milan street takes place, but the getaway is not as planned, and Abel and Raymond end up hiring a boat to get them to Nice. Here I will cloud certain details, moving ahead to a call Abel makes to Paris. He needs his old pals to drive down to Nice and meet him. This they are not eager to do. We see them hemming and hawing and explaining to each other how one needs to check in with his probation officer and another — anyway, what happens is, they recruit a kid none of them knows very well, and hire him to drive down and look for the old man.

This kid is Eric Stark, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo at the dawn of his stardom. He makes the kind of entrance you notice; wearing a loud, tweed overcoat would be perfect for a stickup, because witnesses would remember the coat instead of the guy inside. His entrance is an important moment in movie history. The French New Wave descended more or less directly from mainstream French crime films made in the 1950s, and if there is a missing link in that evolution, it might be this one. Claude Sautet’s “Classe Tous Risques” was made in 1960, the same year Godard’s “Breathless” (1960) came out, and both starred Belmondo, who was the flavor of the year; he had appeared in 10 other recent films, and would have six more starring roles in 1960, usually playing a plug-ugly who was after for the girl.

“Breathless” got all the publicity, and “Classe Tous Risques” hardly opened in America, although Sautet would later make many international successes (“Un Coeur En Hiver,” “Jean, Paul Francois, and the Others”). It arrives now in a restored print with rewritten subtitles, a crisp, smart, cynical film about dishonor among thieves.

Sautet’s film grows out of work like Jacques Becker’s “Touchez Pas au Grisbi” (1954) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Bob le Flambeur” (1955) and shares their affection for a middle-age thief who would like to retire but finds that his old life reaches out and nails him. Jean Gabin gave one of his best performances in the Becker, and Melville’s star, Roger Duchesne, made Bob the High-Roller so likeable that the movie inspired three “Ocean's Eleven” remakes. Ventura lacks Gabin’s star power and Duchesne’s silky regretful heroism, but he has an implacable, lived-in face, and like them he embodies a code his world has abandoned.

By sending a kid for him, Abel’s pals in Paris have insulted his ideas of loyalty and friendship. And who is this kid, anyway? Why did he take the job? Can he be trusted? Why is he fooling around with an actress (Sandra Milo) he just met, who is down on her luck when there isn’t enough luck to go around? After the quick-moving opening episodes, the movie comes down to the relationship between the old guy and the kid — who has no reason at all to risk his life for Abel, except that he knows class when he sees it, understands the code the Parisians have forgotten, and wants to live by it.

The film doesn’t make it a big point, but consider the meetings in Paris where Abel’s pals recruit and hire Eric Stark. As moviegoers we are focusing on (a) Belmondo, so young, his career ahead of him, and (b) the evasions by which the pals hire a kid to do the job they are morally bound to do themselves. But in Sautet’s mind, the scenes might equally have been (c) about the kid listening to them betraying a man who is counting on them. It’s possible that before Eric Stark ever sees Abel, he has already decided that Abel is the real thing, the kind of guy Eric could respect and trust.

Abel asks Eric more than once why he took the job. He doesn’t get much of an answer, but then men in such trades aren’t big on discussing their philosophies. There is also the way Sandra Milo plays Liliane, the new girlfriend. She’s in the tradition of women in gangster movies who sign on with a guy they like, because he treats them right and isn’t a rat. They’re usually running away from a guy who treated them wrong and was a rat. Hard to believe this is the same actress who played Marcello’s pouty, flamboyant mistress in Fellini’s “81/2” (1963). Here she seems dialed down, wearier, just as she should.

“Classe Tous Risques” isn’t a film in the same league with the titles by Becker, Melville and Godard, but how many films are? It’s more like one of those Bogart films that isn’t “The Big Sleep” but you’re glad you saw it anyway. Studying the Hollywood crime films of the 1930s and 1940s, the French gave them their name, film noir, and embraced them with a particular Gallic off-handedness. Their French gangsters crossed hardness with cool and style. In “Touchez Pas au Grisbi,” “Bob le Flambeur” and “Classe Tous Risques,” the heroes have not only loyalty but a certain tenderness, a friendship that survives even when their friends act stupidly and get them all in trouble. In “Breathless” the Belmondo hero acts stupidly himself, and gets himself in trouble, and the modern age of crime films begins.

Ebert’s essays on “Breathless,” “Touchez Pas au Grisbi” and “Bob le Flambeur” are in the “Great Movies” series.