Equipped with over a decade of on-screen labor for many of the world’s greatest cineastes since his first directorial outing, Gael García Bernal exhibits earned creative maturity in his sophomore feature “Chicuarotes,” centered on street performers driven to crime. The Mexican actor who first got behind the camera with 2007’s lackluster “Déficit,” about a pack of wealthy kids’ weekend in the countryside, has evolved his craft substantially, even if the progress fails to yield a fully formed and tonally cohesive outcome.

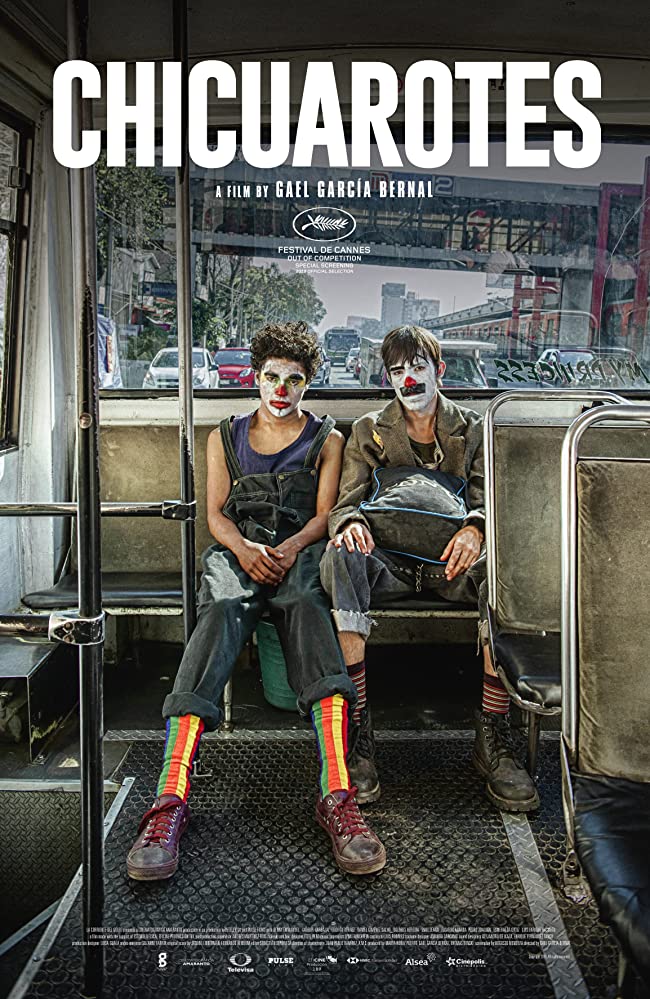

Two teenaged best friends, the dangerously stubborn Cagalera (Benny Emmanuel) and the artistically committed Moloteco (Gabriel Carbajal), ride public transportation in Mexico City telling trite jokes in clown make-up to unresponsive passengers. Fed up with the unfruitful shows, a vivacious opening scene on a microbus sees them devolve from honest entertainers to armed robbers. At gunpoint they obtain what their reluctant audiences would never donate based on their talent.

Alluded to only briefly, the film’s title functions as a both the name of a potent chili that grows in San Gregorio Atlapulco, a neighborhood/village in the Xochimilco municipality of the Mexican capital, and an informal demonym for its inhabitants, who are thought of as innately coarse as the spicy produce. The chicuarotes at hand have developed their worldview amidst poverty and ignorance, living the outskirts of a metropolis that brews violence, homophobia, misogyny, and transphobia.

Augusto Mendoza’s uneven screenplay sets out to merge their grisly and disheartening realities, such as the viciousness of Cagalera’s alcoholic father Baturro (Enoc Leaño) or the kidnapping of a child, with instances of hysterical humor, best exemplified via a traffic stop where two police officers coerce a former bully into apologizing and more. Individual junctures come alive strongly, yet accounted for as a single unit they come across as emotionally contrived.

Mendoza’s writing, however, also seeds what’s most laudable about his and García Bernal’s imperfect undertaking. “Chicuarotes” brims with colloquial ebullience and irresistible authenticity; it’s exactly how many people in certain working-class areas of the city talk in all its unpretentious glory. Evidently, the exemplary casting of Emmanuel and Carbajal, as well as that of veteran thespian Daniel Giménez Cacho (“Zama”) in the against-type nefarious part of Chillamil, contributes the perfect vehicles for the credible delivery of the lines. Nicknames of the most eccentric kind further speak of a place ingrained in its local history and idiosyncrasy.

Emmanuel’s Cagalaera is reminiscent of García Bernal’s Octavio in Iñárritu’s “Amores Perros,” another obstinate character from the lower end of the social strata carrying out clandestine acts to finance a more livable existence elsewhere. Meanwhile, the power imbalance between the two parts in this partnership calls to mind last year’s “Museo,” in which the actor plays a reckless leader who manipulates his faithful, but less strong-willed squire. García Bernal, in front and behind the scenes, surely gravitates towards narratives of fraternal conflict, of young men striving, mostly inadequately, to alter their destinies.

Fascinated by a matchbox presumably from a Las Vegas casino, Cagalaera aches to quickly make enough cash and break out of the toxic surroundings with his more reasonable girlfriend Sugheili (Leidi Gutiérrez). That very desperation, in tandem with unrestrained hyper-masculinity, turns his plans into a death sentence. In contrast, Moloteco, who lives alone in a shack, aspires to emulate legendary comedian and actor Cantinflas, though we get to see little of that peculiar facet.

Lively as they are when first introduced, both chicuatores suffer from writing advancing the plot instead of cultivating more tridimensional antiheroes. We want more of them as complicated products of their circumstances on a quest for agency, and less of the succession of bad decisions in their doomed operation. What García Bernal brings in deftly directing actors (most of them at least), is reduced in impact by way of structural muddling and inconsequential subplots.

Native to the area where the misery unfolds, axolotls, the adorable and endangered amphibians able to regenerate their limbs, float as metaphor for what the misguided youth in the impoverished settlement face. Like the kids, axolotls can no longer survive inside the polluted waters of the canals, so they find safety outside of them. Again, a geographically specific motif that could have suffused the script with thematic richness falls by the wayside after one mention and a painting on a shop’s facade.

Nevertheless, when shooting Cagalera through a chicharrón glass case, setting a tense scene inside a traditional pulqueria, and staging the final sequence of its third act to evoke Felipe Cazals’ seminal “Canoa,” García Bernal stocks up in credibility as he chips away towards sculpting a more well-rounded artwork. His grasp on spirited visual language, an exploit shared with cinematographer Juan Pablo Ramírez, ranks as his most consummate sign of growth. Even though the script tends to venture into cautionary tale territory, that judgment doesn’t infect the sheer curiosity with which this unseen slice of the world is illustrated. “Chicuarotes” flies higher when Cagalera and Moloteco, a memorable duo in spite of their fate, engage their neighbors and each other with a hint of lightness, in tune with the jesters they used to impersonate. At some point, the movie forgets comedy and dwells on cruel calamity. It almost makes one wish García Bernal could reboot it, with a more polished text.