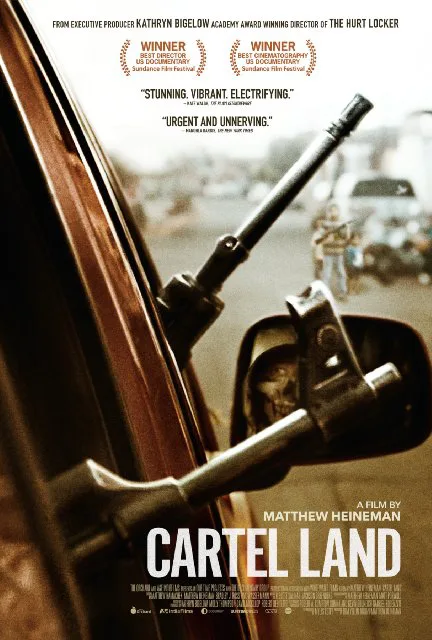

The impulse toward vigilantism on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border is the subject of Matthew Heineman’s “Cartel Land,” an exploration of some of the terrible consequences of ongoing drug wars that have produced far more deaths in Mexico but left people in both countries feeling like their officials’ failure to provide security compels them to take the law into their own hands.

Cutting back and forth between self-appointed border defenders in Arizona and “Autodefensa” groups trying to rid Mexico’s Michoacán state of cartel members, the film provides a fascinating, on-the-ground account of people struggling with situations that range from challenging to horrific. Not for the faint of heart, it sometimes puts its cameras right it the middle of gun battles, for a result that is extremely dramatic even if it also leaves a number of important questions regrettably unanswered.

On each side of the border, Heineman focuses on a self-motivated leader whose strengths can’t disguise certain psychological scars or character flaws. In Arizona, Tim “Nailer” Foley is a leathery veteran whose hard life has evidently contributed to his crusade to defend the U.S. from human and drug traffickers. After enduring physical and emotional abuse from his father, he says, he spent years trying to quell his demons with drugs and alcohol. Once a crisis brought him to the point of going clean, he got a job and led a respectable life until the economy tanked in 2008, after which he sold all his belongings, outfitted himself in paramilitary gear and set off to guard the border.

He and his cohorts – though he started out alone, he has gained followers – spend their days and nights trying to snare illegal immigrants, whom they turn over to U.S authorities. Though at one point we hear a news report saying the Southern Poverty Law Center regards such groups as part of a recent rise of extremism in the U.S., Foley’s crew don’t seem motivated by ideological or racist venom. They seem more like overgrown kids who love to put on camo fatigues, pick up guns and play army in the desert.

The situation in Mexico is much different – and far more dire. The leader here, straight out of a Clint Eastwood movie, is Dr. Jose Mireles, who explains his decision to act against the cartels by holding up a photo of the decapitated heads of three of his former neighbors. Everyone he knows, the doctor says, has been touched by such horrors, which is why in February of 2013, he called together a group of local men and declared that they all needed to decide “how we are going to die” – whether trussed up like animals, or fighting.

The decision to fight led to the creation of the Autodefensas, who declared war on the Knights Templar and sought to drive them out of Michoacán. We see them go into action, wearing their group t-shirts and carrying weapons, breaking down the doors of suspected cartel members, rousting them from bed and driving them from town. In town after town, the vigilantes set about scouring the state clean.

Their actions come in part, they say, because federal and local authorities have failed to act against the cartels, often colluding with or protecting them instead. Their armed vigilantism inevitably leads to an official push-back, as we see in a gripping scene where Mexican Army troops come into a town, disarm the Autodefensas and then find themselves facing angry townspeople, who demand the Autodefensas be given their guns back and then drive the troops from town.

The road to reform does not uniformly favor the Autodefensas, though. After Dr. Mireles suffers severe injuries in a plane crash (a suspected assassination attempt) and has to spend months recuperating, he turns over his command to a hirsute comrade nicknamed Papa Smurf, whose management (and ethical) style seems much different. In one town, we see him facing angry citizens who charge his men with robbing the houses of the suspects they raid, as well as flirting with the local chicas. Bring back the rule of law, the irate townspeople demand. When he recovers and regains his command, Dr. Mireles gently counsels Papa Smurf, “We can’t become the criminals we are fighting against.”

But this is a world where the lines distinguishing criminality and legality, good and evil, right and wrong are constantly blurred, crossed and redrawn. Cartel members run away, return as vigilantes, go to work for the government, then start running drugs and killing people again – in an endless cycle. Despite the bravery and heroism shown by many Autodefensas and men like Dr. Mireles (whose crucial character flaw won’t be revealed here), the picture “Cartel Land” leaves the viewer with is one of a country where official corruption and dysfunction are so profound, and the lure of drug money so powerful, that it won’t shake itself free of its current tragic situation anytime soon.

It must be noted that “Cartel Land” weaves together two stories, and the Mexican one is far more compelling and revealing than the American. Like many verité documentaries, it also involves a trade-off. It explores its subject with a visceral immediacy that’s often thrilling, yet in eschewing interviews with experts and such, it can’t provide information that many viewers will want to know, which ends up feeling like a flaw. To take only one example, what is the legal status of the U.S. vigilantes and what are the government’s official policy and unofficial attitudes towards them?

Finally, we are also left with questions about the filmmakers. In some scenes we see Autadefensas torturing people. In others, we see them making prisoners of cartel members whom we can safely assume will be killed very soon afterwards. What is the filmmaker’s legal responsibility here? What is his moral duty? Such quandaries could serve as the basis of an entirely separate film.