The first time Lytton Strachey saw Dora Carrington, he asked, “Who is that ravishing boy?” When he discovered she was a girl with a tomboy haircut, he was struck dumb; at their first meeting, conversation came to a complete stall, and in embarrassment he picked up a book and pretended to read. He was a homosexual in his mid-30s, dry, bearded, reserved. She was a painter, 15 years younger. Nothing could have been more out of character than for him suddenly to lean over and kiss her, while they were on a walk through the countryside.

But he did.

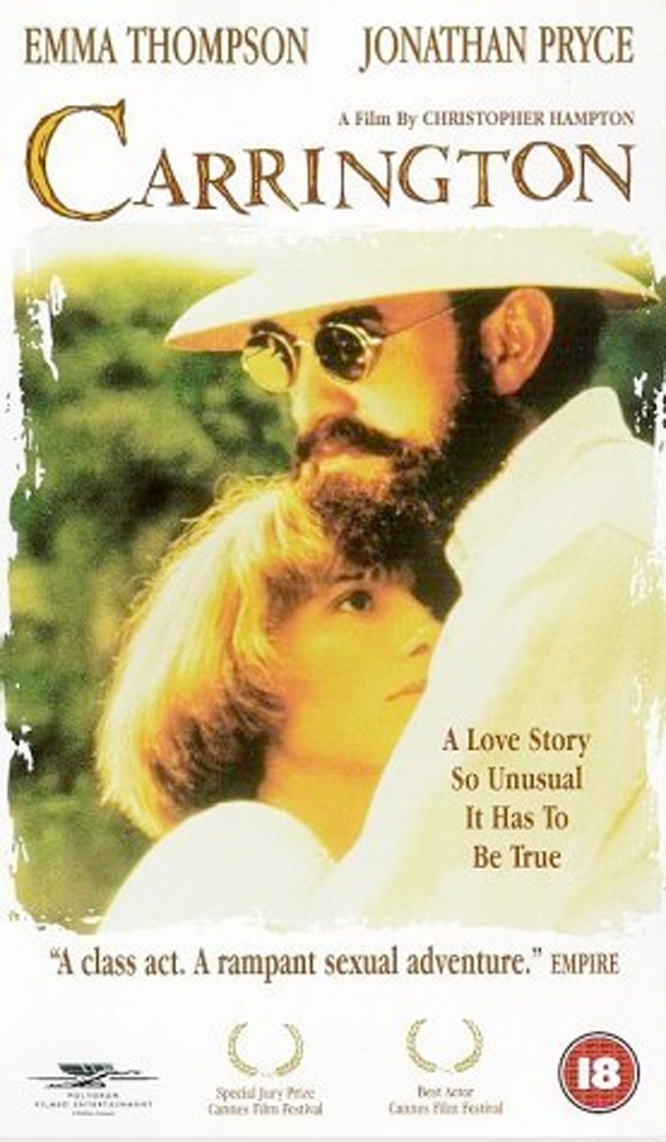

The opening scenes of “Carrington” try to explain the beginnings of one of the oddest romances of the Bloomsbury Group, that gathering of British geniuses, eccentrics and self-publicists that produced no romances that were not odd. In Christopher Hampton’s film, Carrington (she hated the “Dora” and dropped it) visits Strachey’s bedside with a scissors, to chop off his beard in retaliation for the kiss. But then, regarding his sleeping face, she undergoes a sudden transformation into love. Strachey awakens and sees her looming over him: “Have you brought me my breakfast?” Strachey (Jonathan Pryce) and Carrington (Emma Thompson) were in love, after their fashion, for 17 years, until his death, followed shortly by her own. During much of that time, they occupied Ham Spray House, in Berkshire, with a series of other lovers, some of them shared. Carrington eventually married Rex Partridge, who Strachey said should change his name to Ralph, which he did. In one scene, the three of them share the same bed, somewhat uneasily (“There are times when I feel like a character in a play by Moliere,” Strachey said).

Although physical passion no doubt figured at some time, in some way, in all of their lives, they were so reserved about it that the movie leaves us wondering if they wouldn’t really rather engage in repartee than sex. “Ah, semen!” says Strachey. “What is it about that ridiculous white secretion that pulls down the corners of an Englishman’s mouth?” The movie’s only sex scene is so discreet that we can only presume what is happening; during it, Strachey has the facial expression of a person being inoculated.

What they did share was a platonic love, which was real, and endured. Strachey was famous above all for Eminent Victorians (1921), the myth-shattering book that treated such icons as Florence Nightingale to portraits written with skepticism and irony. Like all in the Bloomsbury circle, he was famous for his verbal wit, and Pryce is meticulous in the way he speaks in epigrams while somehow sounding spontaneous. Startled by the pop of a champagne cork, he exclaims, “Good lord, imagine what the war will be like!” Even on his deathbed, he was still in production: “If this is dying, then I don’t think much of it.” The screenplay for “Carrington” was written some 20 years ago by Hampton, a playwright (“Tales from Hollywood”) who won an Oscar for his script for “Dangerous Liaisons.” He decided to direct the film only after Mike Newell (“Four Weddings And A Funeral“) dropped out. Pryce, famous on the London stage for “Miss Saigon” and on American television for Infiniti commercials, was already on board, as was Thompson, who had developed a specialty in unrequited love (“Remains of the Day,” “Howards End“).

What they are up against is a “romance” that fits no conventional mold and is not expressed in ordinary ways. Even at the film’s end, when we get the line, “No one will ever know the happiness of our lives together,” we’re tempted to think, “And no wonder.” Since Pryce’s Strachey is so deeply reserved, it is up to Thompson to project the warmth they both presumably felt, and she does that with her eyes and her silences; she looks at him like a woman in love.

Everyone in the Bloomsbury crowd (Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Roger Fry, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Clive and Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant) were known for freedom, even recklessness, in their choices of romantic partners. A diagram of their love affairs would look like an underground system where every train stopped at every station. And yet they were all so reined in by the British upper-class trait of repressed emotion that when anger and jealousy do emerge (as they do, twice, in “Carrington”), the breach of manners is almost more shocking than the sexual infidelity under complaint.

We are left to guess what emotions seethed beneath the surface of wit and acceptance.

There is one scene in “Carrington” that suggests the depths of Carrington’s heart better than dialogue ever could. One evening after dinner, she wanders on the lawn at Ham Spray House, and through the open, brightly lit windows she is able to observe her lovers, past and present, paired off with their present lovers. As her gaze goes from one window to another, we see her as an outsider. But that is not the whole story, because you could take any of the partners from “Carrington” and put them on the lawn, and pair off the others inside, and the effect would be the same. Somehow, for all of them, standing outside on the lawn must have been part of the fun.