How much work does it take to love yourself as a woman in modern society? How much effort must one put forth to shut out the deafening howl of discrimination and accept oneself as a woman of color, an unapologetically sexual being or a girl who isn’t deemed as conventionally pretty? These questions have recently been tackled in indelible ways by brilliant female artists working within the realm of dance. Under the choreography of Ryan Heffington, Maddie Ziegler exposed the messy emotions trapped within the commoditized faces of women in the acclaimed music videos for Sia tunes such as “Chandelier” and “Big Girls Cry.” Bobbi Jene Smith obliterated the shame so often associated with sexuality in her electrifying performance piece, “A Study on Effort,” the evolution of which can be witnessed in Elvira Lind’s Tribeca prize-winning documentary, “Bobbi Jene.” Though Okwui Okpokwasili’s performance piece, “Bronx Gothic,” is filled with words—both spoken and sung—the first half-hour is comprised entirely of its solo performer dancing silently in a corner of the stage, her back turned to the audience. This radical decision inevitably frustrates some audience members (one man is overheard groaning, “Shoot me now”), but its hypnotic effect proves to be transformative for those willing to lose themselves in the person standing and convulsing before them.

In an era when so many technological distractions are vying for our attention, Okpokwasili challenges us to keep our eyes focused on her until we, in a sense, “become” her. The first third of her performance serves as a sort of overture, fully immersing us in the mood of the piece before a single word is uttered. The intimate venues where “Bronx Gothic” is performed enable Okpokwasili to make eye contact with her audience when she finally turns to face them. She gazes at the seated observers in a way that forces them to consider how they may be read by their mere appearance, a thought that consistently crosses the minds of black women in America. Her goal is to take the viewers off of their protected, elevated perch in the darkness and bring them into her world—the one from her past that continues to haunt her present existence.

Recounting a coming-of-age yarn set in her childhood home of the Bronx, the show is perhaps most poignant when performed in its own location. Even the safe space of the theater can’t prevent the sounds of subway trains and ambulance sirens from blaring through the walls, much like how the security of the Parkchester neighborhood where Okpokwasili grew up wasn’t immune to the threat of violence. Yet no matter where “Bronx Gothic” happens to be staged, the “porous boundary” separating Okpokwasili from her audience is repeatedly blurred. When a fleck of sweat or saliva happens to be flung from the performer onto a member of the crowd, it’s the externalization of Okpokwasili’s intent to have her “blackness get on” the people in attendance until they are consumed.

No filmed footage could replicate the experience of watching “Bronx Gothic” live, but documentarian Andrew Rossi does an admirable job of channeling its power in his movie of the same name. It’s not as adventurous or as thorough a portrait as “Bobbi Jene,” and there are areas where it is conspicuously lacking. As Rossi follows Okpokwasili during the final three-month tour of her show, we catch glimpses of her husband and frequent collaborator, Peter Born. He served as the director of “Bronx Gothic,” but we get little sense of his working relationship with Okpokwasili, aside from one tense conversation regarding the arguable merits of a “Roots” remake. Born questions why so many “black films” tend to be about oppression, leading his wife to argue that the ahistorical attitudes pervading American culture necessitate reminders of our country’s systemic prejudice. The picture may have been enriched by more conversations between this couple, though we are supplied instead with interactions that are nearly as compelling. There’s some very funny banter courtesy of Okpokwasili’s mother, who balks at how her daughter refuses to take a break during the 90-minute performance (“Do they have a doctor there?” she quips), as well as some moving responses from audience members at talkbacks.

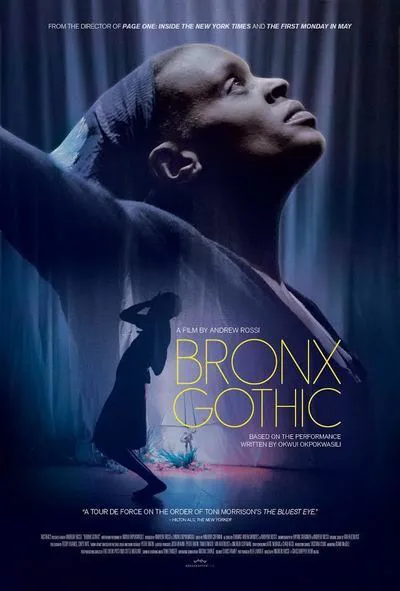

Throughout the film, Okpokwasili is surprisingly candid in voicing her intentions behind each artistic choice in the show, which she insists is not an autobiography but a character piece loosely based on her life and the lives of girls that she knew. As the director of NYC profiles including “Page One: Inside the New York Times” and “The First Monday in May,” Rossi is skilled at involving us in the process of creation, and the best moments in this film juxtapose thrilling performance excerpts with the concepts from which they sprung.

The term “Gothic” in the title is meant to evoke the forbidden spaces where one accidentally enters, culminating in the end of innocence. Once Okpokwasili arrives at the mic, she reads selections of the correspondence that her character supposedly had with her best friend when they were 11 years old in the Bronx. There’s a frankness to the girls’ discussion of their budding sexuality that is both amusing and refreshing, encouraging youth to not be ashamed of their developing bodies. Okpokwasili was pregnant with her daughter when she wrote the show, an added factor that fueled her desire to revolt against the puritanical fear of educated women. Keeping girls ignorant about their own physical functions merely leaves them vulnerable to the predatory forces in society. At the heart of the piece is Okpokwasili’s need to “author herself into existence,” allowing women of color to have their lives acknowledged and validated in a world that “privileges whiteness.” In a riveting montage, Rossi fuses images of mutilated slaves with the recent murders of men like Eric Garner, as Okpokwasili describes the ontological crisis spurred by the endless cycle of watching black bodies be destroyed without consequence. Her stated question of whether she exists if her existence can be so easily erased lends an overarching spiritual component to the show that crystallizes in the final act. As the girls’ identities start to fragment and combine, we wonder whether they are actually shades of the same person, or if they are reflections of ourselves as well.

Rossi’s “Bronx Gothic” is a stirring ode to the liberating catharsis of artistic expression, as embodied by Okpokwasili and Born’s transcendent theatrical masterwork. A lingering question raised by the picture is how black male bodies can cease to be branded as threats, considering how their tough exteriors are so often acquired for the purposes of self-preservation. I was reminded of a good friend whom I walked with many times through the city of Chicago. As we chatted enthusiastically about a variety of topics, he often paused to compliment a passerby or help a family carry a box to their door. I also noticed how the pace in his step would slow on occasion, causing the distance to widen between him and the lone pedestrian ahead of us. When I asked him why he did these things, he told me that as a black man, it was imperative that he go out of his way to avoid being perceived as scary or ill-intentioned. The effort that he put forth on a daily basis boggled my mind and broke my heart. I can’t think of a better example for why the work of artists like Okpokwasili is not only beneficial but entirely indispensable.