Neil Simon’s “Brighton Beach Memoirs” leaves little doubt as to why he grew up to be a successful playwright: Everyone in his family talked in dialogue. The movie feels so plotted, so constructed, so written, that I found myself thinking maybe they shouldn’t have filmed the final draft of the screenplay. Maybe there was an earlier draft that was a little disorganized and unpolished, but still had the jumble of life in it.

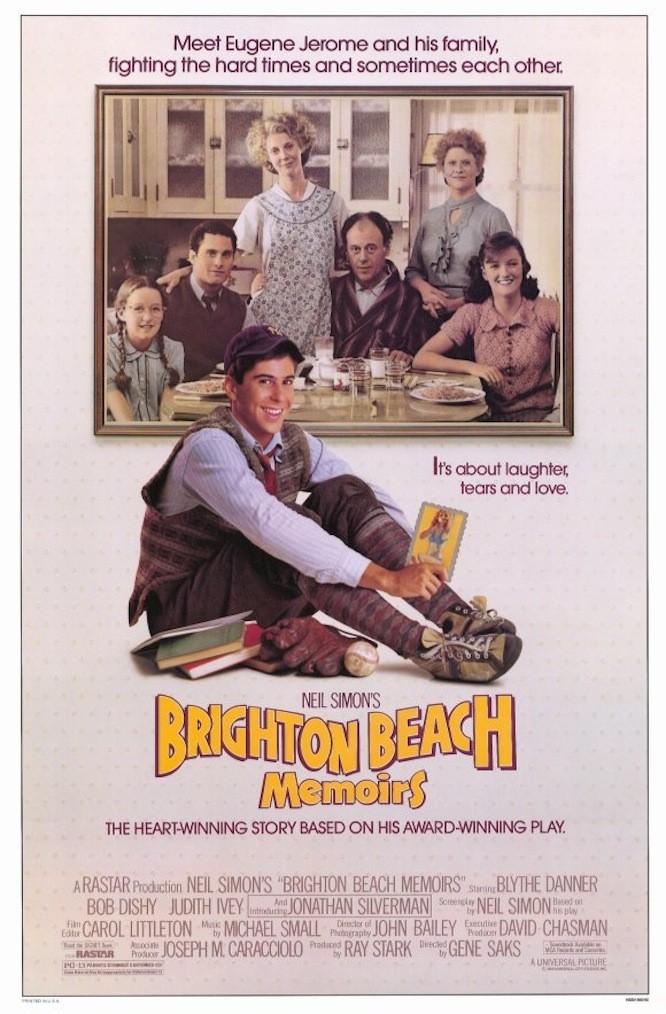

The stage version of “Brighton Beach Memoirs” seemed much more alive than this film. Some of the difference is in the casting of the hero: Jonathan Silverman does not wear as well and is not as infectiously likable as Matthew Broderick, who had the role on stage.

But most of the difference, I think, is in the direction.

The movie was directed by Gene Saks, who directs many of Simon’s plays on both the stage and the screen, and whose gift is for the theater. His plays have the breath of life; his movies feel like the official authorized version. Everything is by the numbers. After we learn that the hero’s family always pronounces diseases with a whisper, we know with total certainty that at least one whispered disease will be “diarrhea,” and that the joke will be carried on for one disease too long.

In “Brighton Beach Memoirs,” the first in an autobiographical trilogy by Simon, he remembers his early adolescence. Still ahead were the uncertain war years of “Biloxi Blues” and the family wars and heartbreaks of “Broadway Bound,” his current stage success. Simon tells his story through the eyes of Eugene (Silverman), a kid who seems more like a future go-fer than a future playwright, and whose life is consumed by a great and solemn desire to see at least one naked girl.

Eugene lives in a home filled with relatives; not only his parents and an important older brother, but also an aunt and a cousin. In the stage version, I could feel the crowding, the way the overlapping lives within the house raised the family’s collective temperature. In the movie, there’s no sense of other lives being lived through the walls, and the characters seem to walk on for their assigned material and then evaporate.

Nor does the Brighton Beach neighborhood really come to life, despite untold effort spent to dress the street where Jonathan lives.

When he leaves home, it’s usually to go to Greenblatt’s grocery, where his mother sends him several times a day (another standing joke). On his way there and back, he never seems to encounter anyone except characters specifically involved with the plot. This isn’t a Brooklyn teeming with life and excitement; it’s a backdrop for schtick.

Sometimes the family feels like backdrop, too. Jonathan’s mother is intended to be one of the great towering figures of his life, but Blythe Danner doesn’t bring much force to the character. Danner proved in “The Great Santini” that she can bring great passion to the role of the mother of a troubled family, but in this movie there seems to be an invisible line she’s not allowed to cross, a certain level above which she must not raise her voice. There’s that feeling all through the movie – the feeling that a safe middle ground has been established, and that nothing will grow too fearsome, too passionate or too angry.

Not long ago I went to a memorial service for Sydney J. Harris, the Chicago Sun-Times columnist, and I heard Saul Bellow remember the adolescence of his best friend. They walked back and forth between their homes, talking late into the night. They argued about ideas and everything else. Harris wrote a novel and Bellow wrote the introduction, and they decided it should be taken to a New York publisher, so Harris stuck out his thumb on Division Street and hitched all the way to New York, and Bellow kept his secret – even when his older brother and Harris’s mother marched him in for questioning at the Missing Persons Bureau.

Bellow spoke in direct, affectionate sentences that captured the passion of that time of their lives, the seriousness of their convictions. He created mental pictures of kids who took risks and put themselves on the line, and as I listened to him speak, I reflected on how pale everyone seemed in “Brighton Beach Memoirs,” by comparison – even though the milieus are so similar. It’s all too even, too smooth, too easy. Simon and Saks should have taken some chances and cut closer to the bone.