“But this ship cannot sink!”

“She’s made of iron, sir! I assure you, she can—and she will.”

—exchange between Bruce Ismay and Thomas Andrews in “Titanic” (1997)

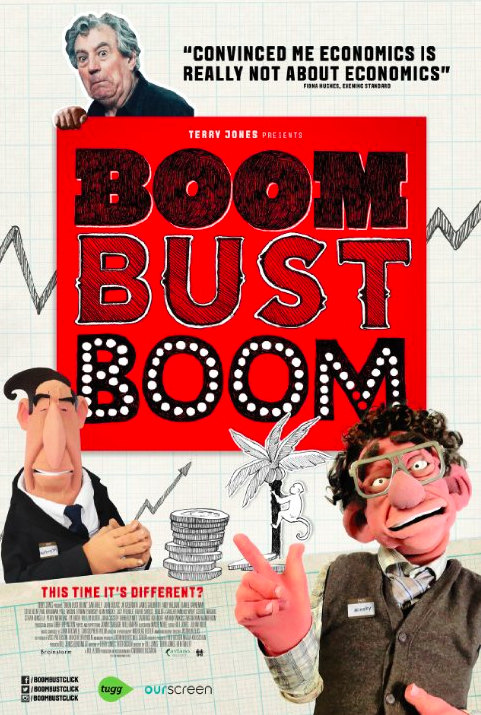

Clocking in just over an hour, “Boom Bust Boom” is the most easily digestible educational video about the financial crisis I’ve seen. It’s less muddled than “The Big Short” and less harrowing than “Requiem for the American Dream,” and though it covers much of the same territory, it does so with a playful irreverence typical of its co-writer, co-director and host, Terry Jones. After brilliantly skewering the absurdity of human nature with his Monty Python cohorts, Jones is an ideal person to tackle the delusions and greed that have led mankind into a cyclical string of disasters. In order to illustrate the herd mentality of capitalistic economies, Jones borrows a scene from his 1979 classic, “Life of Brian,” in which a crowd declares, “We are all individuals!” in zombie-like unison.

With its frequent use of puppetry and quirky animation, “Boom Bust Boom” suggests what an old-school episode of “Sesame Street” would’ve played like, had it focused solely on the subprime crash. There’s no doubt that its “letter of the day” would’ve been B (for Bubble). According to playwright Lucy Prebble, one of the film’s numerous talking heads, a bubble is “a state of hope and excitement—and stupidity.” It is an isolated moment of euphoric stability that is guaranteed not to last, yet nevertheless causes us to indulge in the sort of recklessness that led Julie Hagerty to lose her nest egg in “Lost in America.” Lending mortgages to people who cannot afford them should be considered a crime, and yet the criminals are routinely rewarded with government bailouts. The biggest laughs in the picture arrive courtesy of recycled clips from “South Park,” particularly the one where men in suits determine the most prudent move to salvage an insurance company. They chop off a chicken’s head and place its flailing body on a board filled with optional solutions, such as “Tax The Rich,” “Run For The Hills” and “Coup d’État.” Sadly, the chicken lands on “Bailout,” which happens to be only a feather’s length away from “Socialize!”

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of this analysis from Jones and his writing partner, economics professor Theo Kockren, is the denial that has continuously allowed a broken system to operate unquestioned. Even Alan Greenspan appears to have forgotten his fleeting moment of clarity, when he publicly admitted that free-market economics and deregulation may not have been as infallible as he once believed. The overarching problem, as noted by New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, is that the neoclassical economic model favored by universities doesn’t take into account the foolishness that is so often fueled by greed. The model is, at best, a helpful “fairy tale” that could prove to be a trap when mistaken for the truth. In a fascinating sequence that could be expanded into a feature-length documentary of its own, Jones explores the research of Laurie Santos, a psychology professor who has found parallels between the behavior of monkeys and humans in terms of their shared irrationality. When presented with two identical sums of food, a monkey will choose the sum that promises to be larger, even though that promise has repeatedly proven to be false. Santos believes that our market strategies are governed by the same archaic evolutionary instincts, and her argument is frighteningly convincing.

Conspicuously absent from economics classes touting the eminent security of capitalism are any mention of the previous burst bubbles that mirrored our present crisis, from the “tulip mania” of 1637 to the South Sea bubble that lost Sir Isaac Newton a fortune. Our age of prosperity prior to 2008 was not all that different from 1928, when President Calvin Coolidge (appearing here in puppet form) gushed about America’s bright future during his State of the Union address. His words eerily echo those of President George W. Bush’s own speech in 2006, which Jones juxtaposes with his puppet Coolidge flanked by a sarcastic choir. America’s current unequal distribution of wealth isn’t all that different from the Roaring ’20s either, considering that the top five percent of Americans had a third of all personal income prior to the 1929 crash. And just as prophets like Roger Babson and Paul Warburg warned of the impending Great Depression years before it occurred (and were, naturally, ignored), economist Hyman Minsky was posthumously hailed for his financial instability hypothesis, which went unheeded until it inevitably came true eight years ago. The film’s most inspired use of puppetry enables Minsky’s real-life son, Alan, to have a reunion with his father, whose words are bracingly relevant even when delivered by a mouth made of felt.

The solution proposed by Jones and his subjects is succinct: the system needs to change and people need to be better educated. It’s encouraging to observe a group of students eagerly aspiring to become economists with “a critical mind” well-aware of the risks, as opposed to a blind self-assurance. Watching “Boom Bust Boom,” I couldn’t help thinking of the monstrous hubris and short-sightedness that famously destroyed the RMS Titanic, and could potentially cause the rest of the world to end up underwater, thanks to corporately funded efforts to discredit the threat of global warming. We are, alas, a sinkable species without nearly enough lifeboats. To deny that fact would be akin to embracing defeat.