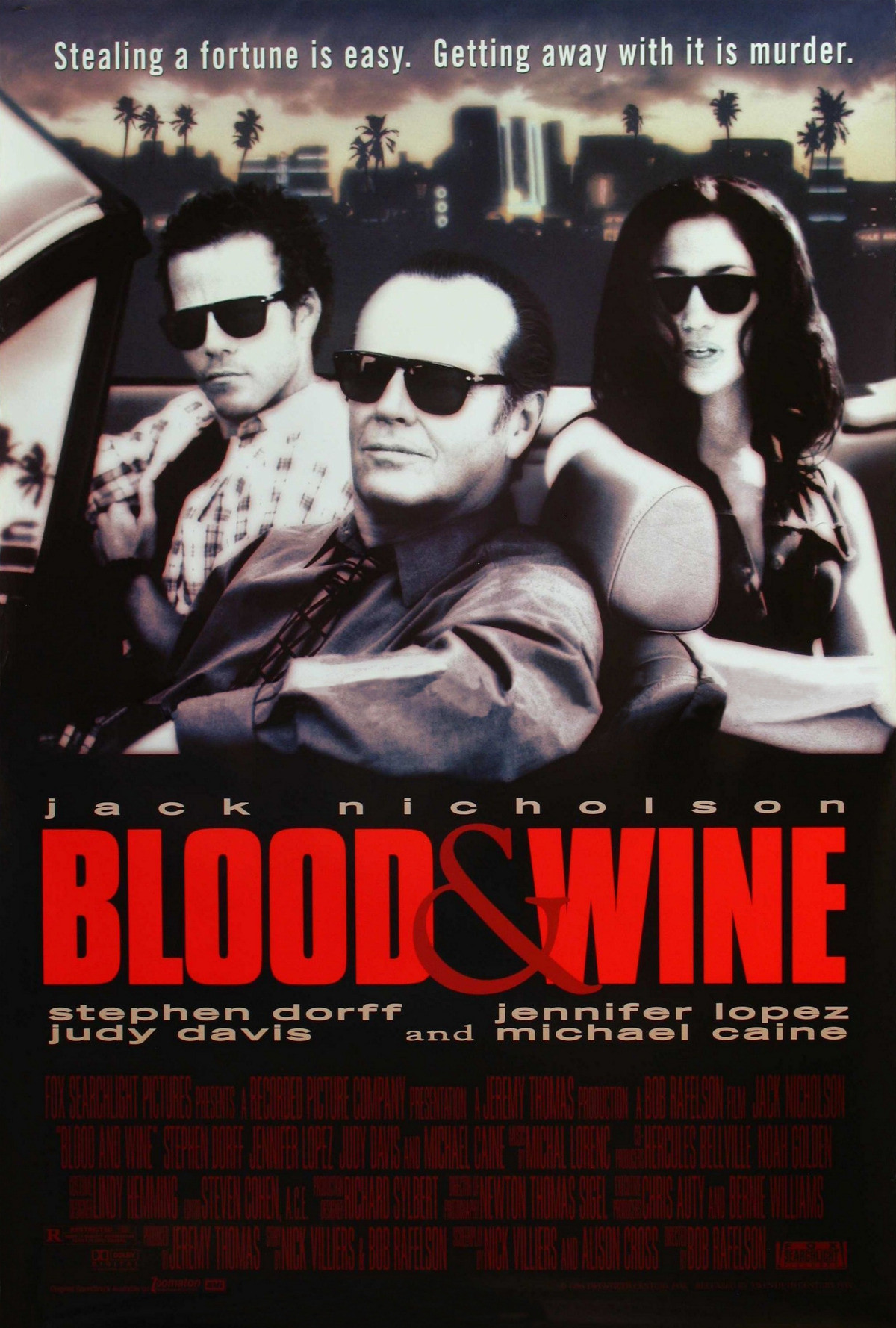

“Blood & Wine” is a richly textured crime picture based on the personalities of men who make their living desperately. Jack Nicholson and Michael Caine are the stars, as partners in a jewel theft that goes wrong in a number of ways, each way illustrating deep flaws in how they choose to live. It’s a morality play, really, but dripping with humid sex and violence.

Nicholson is a Florida wine dealer whose business is going broke, whose wife (Judy Davis) wants to leave him, and whose stepson (Stephen Dorff) hates him. He hooks up with a tubercular British exile (Michael Caine) to steal a million-dollar diamond necklace from the house of some rich people. But it is all so much more complicated than that and includes Nicholson’s sexual liaison with the rich family’s nanny (Jennifer Lopez). That’s just the set-up. The plot gets *really* complicated.

“Blood & Wine” was directed and co-written by Bob Rafelson, who directed Nicholson’s first great picture (“Five Easy Pieces,” 1970) and also worked with him in “The King of Marvin Gardens” (1972), “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1981) and the unsuccessful “Man Trouble” (1992). This is a return to the tone of their best work; all the major characters are villains or victims. Director Paul Schrader was telling me not long ago that movies have passed out of an existential period and into an ironic period. In that case, “Blood & Wine” is a throwback, because there is nothing ironic about these characters except what finally happens to them. The plot is lurid and blood-soaked beyond description, but is handled seriously, as a string of events illustrating the maxim that bad things happen to bad people.

Much of the film’s delight depends on what happens to the diamond necklace after Nicholson and Caine finally steal it. The theft itself is not hard. “Rich people are so cheap,” the Caine character says. “They’ll spend millions on a necklace, and lock it in a tin box from Sears.” I will not spoil the fun of discovery by describing the travels of the necklace once it is stolen. Instead, I’d like to observe some wonderful actors hard at work.

This is one of Nicholson’s best performances, because he stays willingly inside the gritty, tired, hard-nosed personality of Alex Gates, who is failing at love, business and crime. He nevertheless remains a romantic at heart, and his romance with young Gabrielle (Lopez) is genuine: They love each other, even though she is unwise to believe his stories about how they’ll soon be unwinding in Paris.

What makes the performance believable is in the details, in the way he tells his stepson to put on a shirt before leaving the house, or in the way he and his wife have a practiced shorthand, condensing all their old arguments into short, bitter trigger-words.

Michael Caine, who can sleepwalk through bad movies, can bring good ones a special texture. Here he is convincing and sardonically amusing as a wreck of a man who chain-smokes, coughs, spits up blood and still goes through the rituals of a jewel thief because that is who he is. He is capable of sudden violence (pounding Nicholson with a golf club, he observes, “That was an acupuncture point”). But he almost inspires sympathy as a crook who has labored a long time at a hard profession and has nothing to show for it.

The other roles are given almost equal weight; the supporting characters aren’t atmosphere, but are crucial to the story, and one sign of the good writing is in the way other relationships (the mother and her son, the son and Gabrielle) affect the outcome of the plot. In a bad crime movie, people do what they do to fit the plot. In a good crime movie, people are who they are, and that determines the plot. Judy Davis, for example, projects a fierce wounded anger that adds a whole dimension to her marriage; she has given this man her money and trust and has seen both thrown away.

Then there is the way that Rafelson handles the movie’s love triangle, if that is what it can be called. Gabrielle has no way of knowing the relationship between the man she loves and the man she is beginning to love, and Rafelson walks a fine line; when she’s forced to choose, we honestly have no way of knowing which way she’ll turn.

One early review of this film said it had a “’70s feel.” Perhaps that means it takes its plot seriously, and doesn’t try to deflect possible criticism by hedging its bets by pretending there is an ironic subtext. I like movies like this: I like the way the actors are forced to commit to them, to work without a net. When Rafelson and Nicholson find the right material, it must be a relief for them to fall back into what they know so well how to do, to handle hard scenes like easy pieces.