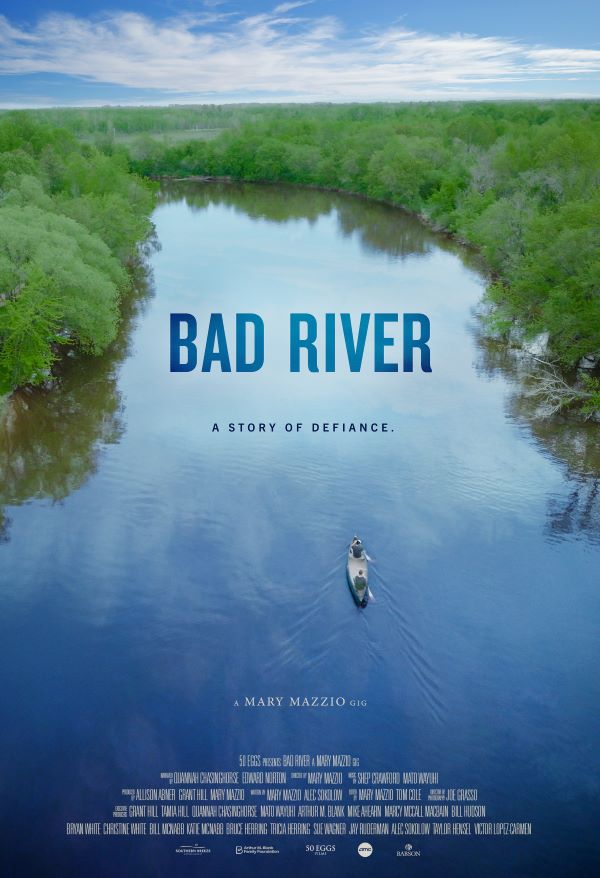

There are so many stories of environmental tragedy and historical malfeasance against the Indigenous people of this land, but we owe it to both this country’s past and future to listen to them all. Mary Mazzio’s “Bad River” has some production elements that frustrated me, but it tells an important story, another call to think about not only the ancestors who made this land but also how we’re leaving it for future generations. Narrated by Quannah ChasingHorse and Ed Norton, and produced by a team of Indigenous creatives that includes Mato Wayuhi and Taylor Hensel of the amazing “Reservation Dogs,” “Bad River” is playing in theaters this weekend, a notable amplification of a noble message.

The Bad River Band or Bad River Tribe are a tribe of the Ojibwe people in part of northern Wisconsin along Lake Superior, one of the most vital bodies of water on the continent. Mazzio speeds through the history of the mistreatment of Native Americans from their representation in pop culture like “The Searchers” to their fights for sovereignty. The main thrust of her film centers on the Line 5 Pipeline, the property of a company called Enbridge that is basically found on Bad River land.

When an eroding pipeline is discovered, a battle ensues to remove it, but Mazzio’s approach isn’t merely to focus on this one case, using interviews with locals to sometimes try and tell too many stories at once. It’s admirable and totally understandable to want to raise awareness about the many issues facing these cultures in the 2020s and emphasize a return to tradition, but the film often drifts from the David-and-Goliath story that could have anchored it. It’s also heavy with sound bites from interviews and over-scored with near-constant music. There’s a remarkable scene late in the film in which the arc of the river is tracked like the arc of a life and I longed for more material like that—rich, specific, focused—and less that felt like a history lesson.

If it feels like Mazzio could have made an entire series out of the many issues at play in “Bad River,” it also feels a bit churlish to come down too hard on a film that’s using every minute of its chance to amplify important issues. It ultimately places the Line 5 Pipeline in a legacy that includes the Dawes Act, the disappearing of Native American children, and the Indian Relocation Act. “Bad River” gains a cumulative power in the way it consistently counters these tragedies with moving interviews with the proud, vibrant people who have refused to leave, illustrating the courage of resistance that takes place across generations. If it’s sometimes like a movie that’s trying to tell a few too many stories at once, it’s hard to blame it. There are so many stories that need to be heard.