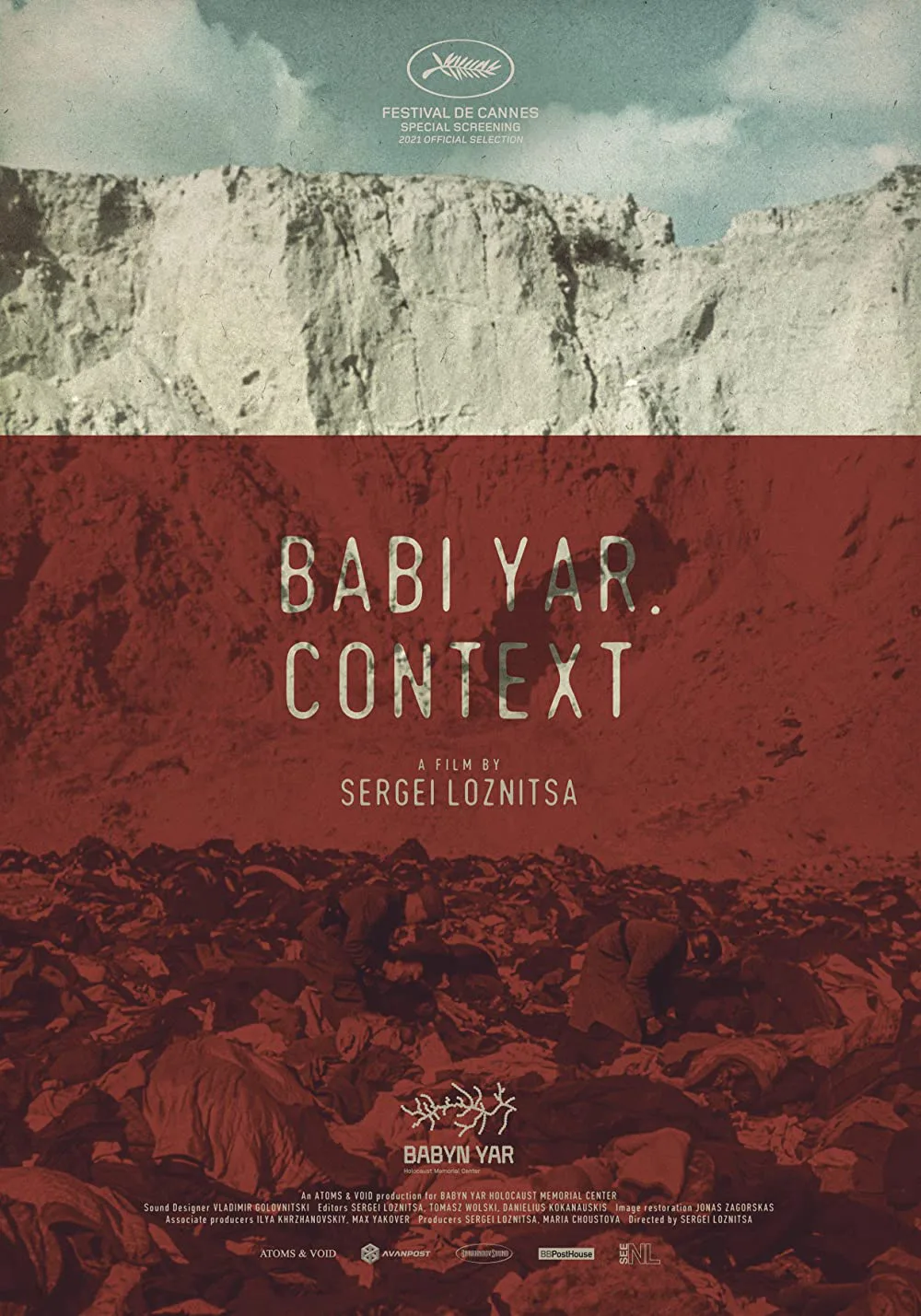

In 1941, members of the Nazis’ Sonderkommando and Police Regiment South units (with assistance by the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police) killed 33,771 Jews in the Babi Yar ravine to the northwest of Kyiv. Babi Yar’s Jews were slaughtered “without resistance from the local population,” according to Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa. Those words are a direct quote from Loznitsa (“State Funeral,” “My Joy”). They were taken from the press notes for his “Babi Yar. Context,” an unsettling Dutch-Ukrainian documentary that reconstructs a timeline of events surrounding the 1941 mass murder at Babi Yar.

“Babi Yar. Context” features a cache of newly restored documentary footage, plus a brand new audio soundtrack, complete with a dense soundscape of recreated ambient noises (courtesy of sound designer Vladimir Golovnitski) and dramatized/recreated dialogue. This new soundtrack is distracting and inadvertently reminds viewers of the movie’s apparent mission of bringing life-like immediacy and dramatic tension to the already disturbing component footage. That and Loznitsa’s stated intentions—ex: the period in the movie’s title, followed by the imposing stand-alone phrase “Context”—sometimes reduce history to a surreal spectacle.

As a political commentary, “Babi Yar. Context” is fairly straightforward. Loznitsa exhumes a crime using pseudo-naturalistic footage that ultimately concludes in 1952, when the Babi Yar ravine was turned into a landfill for the disposal of industrial waste. Loznitsa insists, in multiple interviews, that he did not alter the content of his documentary’s footage, but you can tell some things from this concluding scene, especially the obscene churning sounds that seem to come from a photographed drain pipe.

Through footage that precedes and then follows the Babi Yar massacre, Loznitsa suggests, in no uncertain terms, that the surviving locals were complicit. That damning sentiment is obviously supported by the movie’s vital new footage, but that footage is never so meaningful as to overcome the distracting nature of Loznitsa’s obvious streamlining/narrativizing of the past.

Loznitsa first establishes the concept of the Babi Yar massacre as a rupture in the daily life of citizens from nearby Lvov and Kyiv. We hear birds chirping, feet scuffing, and people murmuring as they get around. They’re never as loud as the succeeding rumble of motor engines or the voracious churning of fire and smoke as they engulf nearby burning buildings. Does these vivid, realistic sounds humanize the past, by re-arranging the every-day textures of the past as a fussily re-arranged time capsule? The history of this newly revived moment now appears, in Loznitsa’s movie, like an over-determined collection of singular details. Viewers are overwhelmed by this enhanced footage, but never really encouraged to consider the meaning of whatever we’re looking at. Not beyond any individual scene’s visceral effect, at least.

Loznitsa shows us two banners that greeted the Nazis earlier that year, including one that translates to “long live the leader of the German people, Adolf Hitler.” He also shows us the looks of gratitude and relief on the faces of Red Army prisoners of war near Kyiv when, in 1941, they were released into the custody of their wives and families. This scene adds dramatic tension to later scenes that highlight the selective remembrance, self-absorption, and canned catharsis of the political theater surrounding the Babi Yar massacre, including the testimony of surviving eyewitnesses in 1946 as well as the public hanging of a few Nazi perpetrators that same year.

Rather than focus on the representative actions of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Loznitsa highlights the presence of the German Governor-General Hans Frank, whose arrival is celebrated in a Stanislau parade just days after the killing at Babi Yar. Loznitsa makes the Ukrainians’ embrace of Frank seem not only crass, but also like a premature celebration of their aspirational (ie: unfulfilled) pact with the Nazis. In this loaded context, Babi Yar’s murdered Jews seems to prove what we now know all too well—that the Nazis could not be trusted and that the Ukrainian nationalists were foolish to have ever helped their oppressors. Still, Loznitsa does not explicitly condemn the OUN or their collaborators (he explains why, to some extent, in this conversation with the Chicago International Film Festival’s Anthony Kaufman). Instead of positioning Babi Yar as a calculated act of genocide, Loznitsa encourages viewers to wallow in residual guilt through a vague sort of counter-mythmaking.

The dual nature of “Babi Yar. Context” as both an essay movie and a cut-up historic document might create an uneasy tension with viewers who would like to know more about whatever they’re looking at. If nothing else, Loznitsa succeeds at being upsetting. It’s hard to deny the impact of intertitles that feature quotes from Vasily Grossman’s sorrowful 1943 essay “Ukraine Without Jews” or a local Kyiv newspaper’s article that, in October 1941, claimed that the Nazis were merely “fulfilling the desires of the Ukrainians.” Even more upsetting: the uncomfortable silences that punctuate the movie’s deceptively nuanced soundtrack. The loss of thousands of people weighs heavily on their mourners, but Loznitsa doesn’t always seem to be comfortable sitting with that burden.

Now playing in select theaters.