Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary are two of the most notorious fallen women in literature. Karenina is prepared to lose all the advantages of high society in favor of the man she loves. Bovary abandons the man who loves her in an attempt to climb socially. As portrayed by Leo Tolstoy and Gustave Flaubert, both women are devastated by the prices they pay.

These are two of the great roles for many actresses and irresistible challenges for many filmmakers. There have been more than a dozen film versions of Karenina, most famously by Greta Garbo (1927 and 1935) and Vivien Leigh; almost as many of Bovary, notably by Isabelle Huppert, Jennifer Jones and Pola Negri (Mia Wasikowska will play her next year).

I mention these details to ask myself: What makes the two roles so enticing that every good actress must sooner or later read the novels and start to daydream? Both are mothers who essentially choose to abandon their single children. Both are the center of attention and gossip within their own circles. Both use opera houses as a stage for their affairs. Both pay dearly for their adulteries. The big difference is that Karenina is driven by sincere passion, and Bovary by selfishness and greed. Karenina inspires pity, Bovary gets what she deserves.

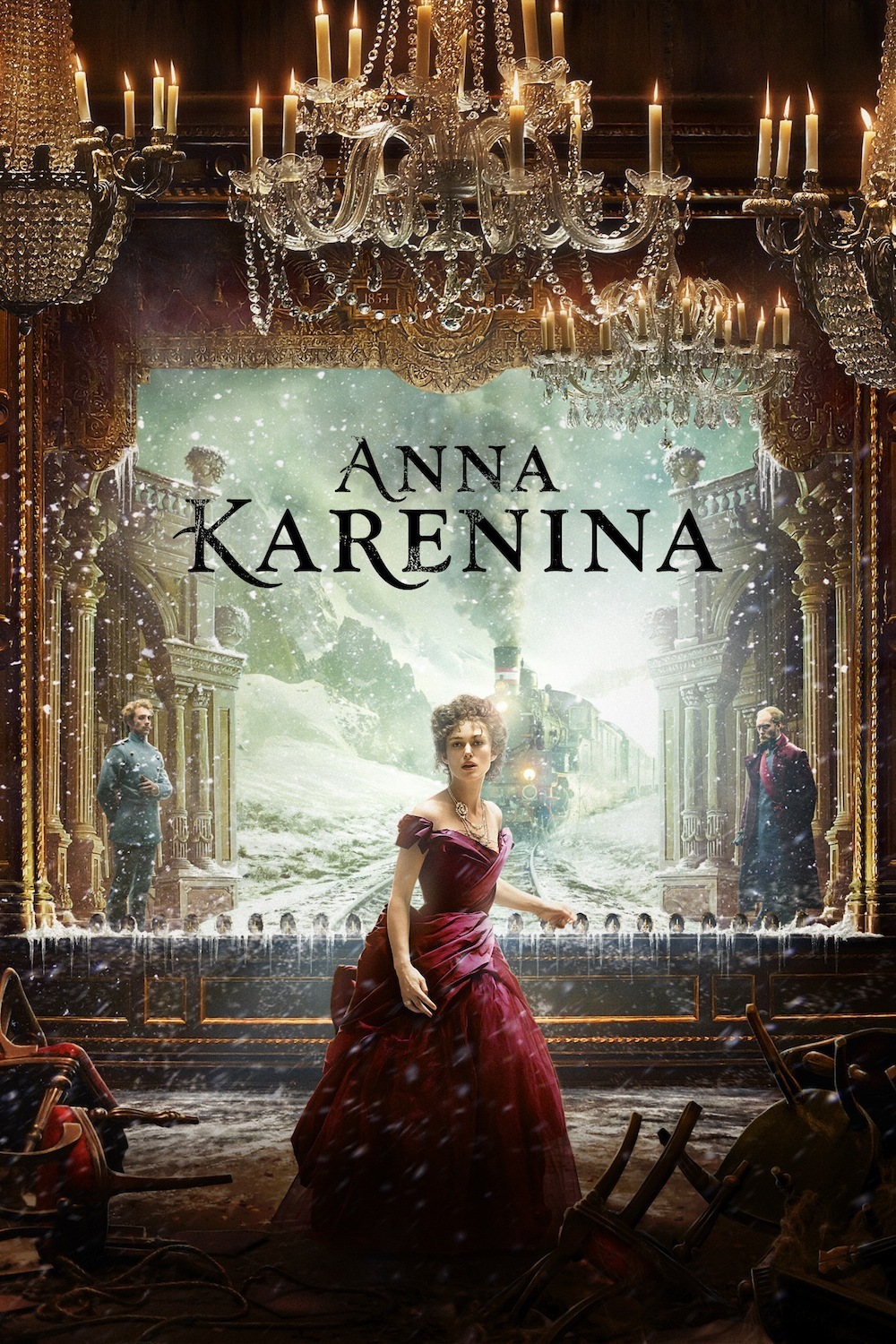

In Joe Wright’s daringly stylized new version of “Anna Karenina,” he returns for the third time to use Keira Knightley as his heroine. She is almost distractingly beautiful here and elegantly gowned to an improbable degree. One practical reason for that: As much as half of Wright’s film is staged within an actual theater and uses not only the stage but the boxes and even the main floor — with seats removed — to present the action. We see the actors in the wings, the stage machinery, the trickery with backdrops, horses galloping across in a steeplechase.

All the world’s a stage, and we but players on it. Yes, and particularly in Karenina’s case, because she fails to realize how true that is. She makes choices that are unacceptable in the high society of St. Petersburg and Moscow, and behaves as if they were invisible. She doesn’t seem to realize the audience is right there and paying close attention. She believes she can flaunt the rules and get away with it.

When we meet her, she is the pretty young wife of the important government minister Karenin (Jude Law). He is affectionate, but dry and remote. The love she lacks for him she lavishes on their 8-year-old son. At the train station to meet Dolly, the wife of her brother, Count Oblonsky (Matthew Macfadyen), she sees the dashing young officer Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), and for both of them, it’s love at first sight. He seems very young and perhaps not schooled in society’s rules. She should know better.

All society appears in public at the opera and grand balls (both staged by Wright in the theater), and after Anna and Vronsky meet at a ball, the die is cast. In this film, Wright and his screenwriter, Tom Stoppard, make adequate room for a landowner named Levin (Domhnall Gleeson), who for Tolstoy was the third major character and certainly the most attractive. Levin represents Tolstoy’s ideas in the novel: He is for abolishing serfdom and liberating his own serfs and has a near-mystical bond with the land and its cultivation.

He hopes to marry Kitty (Alicia Vikander), who has a crush on Vronsky, but at the ball, Vronsky has eyes only for Anna, and the outcome is happiness for Kitty and Levin.

Anna’s husband is not blind and soon knows about her affair. He is very firm. If they continue (affairs are not unknown in their circle), she must be discreet and secretive. Anna’s heart is too aflame to conceal her love with Vronsky, and she pays the price of separation from her husband and her beloved son. Society is satisfied. She has sinned, and she has been punished. Her punishment is far from over, and the lesson she dearly learns is that passion may be temporary, but scandal is permanent.

This is a sumptuous film — extravagantly staged and photographed, perhaps too much so for its own good. There are times when it is not quite clear if we are looking at characters in a story or players on a stage. Productions can sometimes upstage a story, but when the story is as considerable as “Anna Karenina,” that can be a miscalculation.