Watching “Shine,” I found myself wondering about the dynamics of the marriage between David and Gillian Helfgott. Could it have been so simple as a loving woman healing a troubled man? At the same 1996 Sundance Film Festival that introduced “Shine” to North America, there was another Australian film, one that arrived with seven Australian Academy Awards, including best picture, actor, actress and director. It also dealt with romance and mental illness. Yet somehow it didn’t cause the same stir, perhaps because it was the very opposite of a feel-good movie.

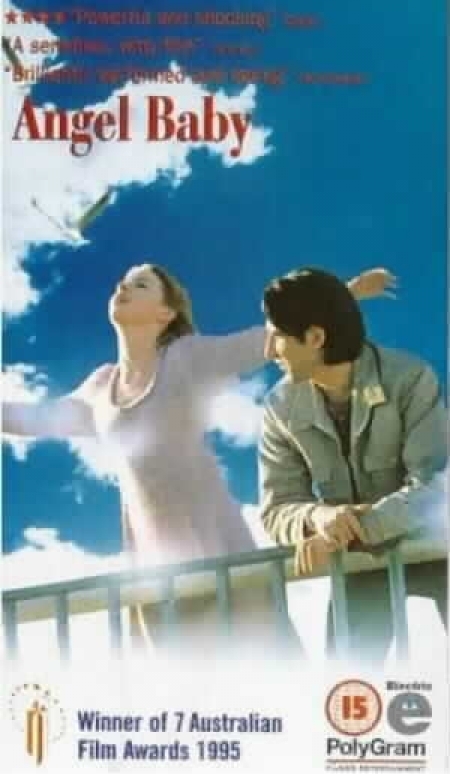

Michael Rymer’s “Angel Baby” tells the story of Harry and Kate, who meet at an outpatient clinic for mental patients, who fall in love, who seem for a time to be blessed with each other, and who then make the mistake of growing overconfident and discontinuing their medication.

The results are inevitable, but this is not the film of unredeemed dreariness that story line would suggest; I have noticed in any number of Australian films a pull toward human comedy, an appreciation for the quirks and eccentric fillips of characters who may be doomed but rage cheerfully against the dying of the light. Even in their final downward spiral, Kate (Jacqueline McKenzie) and Harry (John Lynch) see hopeful omens.

But then Kate’s whole life is controlled by omens, which she receives from her guardian angel, named Astral. His method of communication is the Australian version of “Wheel of Fortune.” As the letters are turned over and the underlying phrases are revealed, Kate takes careful notes; she learns she’s pregnant, for example, when the Australian version of Vanna White turns over letters spelling out “Great Expectations.” And she believes it is Astral who is residing in her womb.

The movie avoids many of the cliches often found in pictures about mental illness. The professionals in the film, for example, are sensitive and competent. And in the film’s early scenes, it looks as if Harry and Kate might indeed be successful in their quest for love.

Harry is a nice man, who helps his young nephew banish monsters from the bedroom (he draws a magic chalk circle around the child’s bed), and when he’s around Kate, his face almost always reflects tender concern. She is more out of control; after a careless roller-blader in a mall store cuts her, she grows hysterical at her loss of blood and even licks some of it up off the floor. When they decide to move in together, the choice seems promising, but then they make the fateful decision to stop their medication.

John Lynch is an actor who is ready for wider recognition (you may remember him as a teenager in “Cal,” or as the hunger striker Bobby Sands in “Some Mother’s Son“). In “Angel Baby,” he has in some ways the more difficult role; Jacqueline McKenzie’s Kate is on her own wavelength, but he has to gauge her condition, react to it and somehow monitor his own health as well. And there is an intensity that goes along with loving anyone who is disturbed–an uncertainty during the happy moments that makes them seem poignant and precious.

That’s what the movie captures, and that’s the tone that prevails even during the harrowing scenes of suffering.

Those who shed tears during “Shine” are likely to be dry-eyed during “Angel Baby.” The movie’s only release is a touching fantasy in the last shot. No marriage is simple, and no love story is uncomplicated. Watching this film, I realized that while I admired “Shine” and was moved by it, “Angel Baby” comes closer to dealing honestly with a fraught relationship. As Tolstoy might have written if he had lived longer and seen more movies: All happy endings are the same, but every unhappy ending is unhappy in its own way.