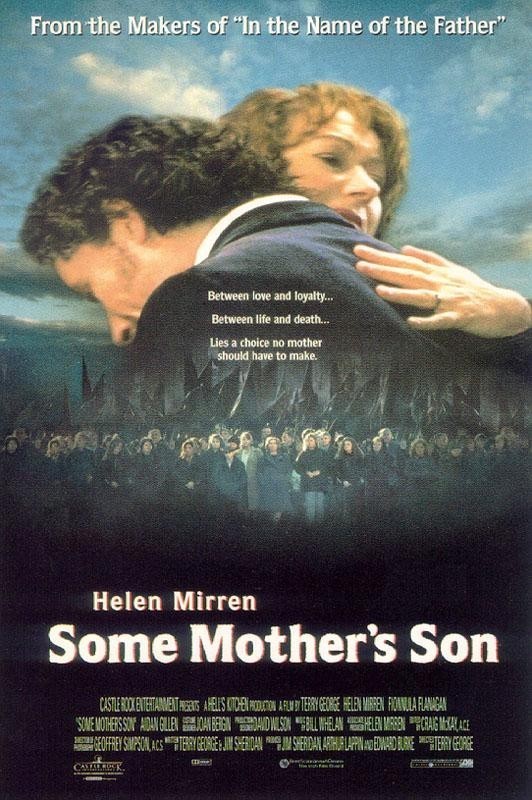

If the long struggle between the British and the Irish had been carried out only on movie screens, the Irish would long since have been the victors. The Irish film industry, one of the most creative and interesting in Europe, has returned time and again with fierce zeal to the Troubles, most recently with Neil Jordan’s “Michael Collins,” and before that with “In The Name Of The Father,” “Cal” and “Hidden Agenda.” Now comes “Some Mother’s Son,” a fictionalized account of the 1981 IRA hunger strikers of Belfast’s Maze Prison, who broke the iron policies of Margaret Thatcher after 10 of them died. (The issue: As self-proclaimed political prisoners, they did not want to wear criminals’ prison uniforms.) One of the martyrs was Bobby Sands, who was elected to Parliament while in prison, and whose funeral procession attracted 100,000 mourners. The film is not really about him, however, but about two fictional hunger strikers and their mothers–who are asked, after their sons lapse into comas, to authorize intravenous feeding. The mothers come from very different parts of the community. Kathleen Quigley (Helen Mirren) is a pacifist, a schoolteacher who doesn’t know her son Gerard (Aidan Gillen) is even in the IRA. The other is Annie Higgins (Fionnula Flanagan), whose son Frank (David O'Hara) has been implicated in a fatal mortar attack on British troops. When both men join Sands and the other hunger strikers, the mothers become friends, even though Annie steadfastly supports her son’s readiness to die, and Kathleen cannot see how any mother could make that decision. (The dead British soldiers, she says, were also “some mother’s son.”) The movie, directed by Terry George (who co-wrote “In the Name of the Father”) intercuts three main strands: Life inside the prison, life for the two mothers, and the attempts by Thatcher’s government to hold firm in the face of mounting sentiment for the strikers. The face of Britain in the movie is represented by a man named Farnsworth (Tom Hollander), who takes a hard line and defends it with the least possible grace, sympathy or intelligence. It might have made the movie more absorbing if Farnsworth had been allowed some human feelings, but George saves those for the chief IRA negotiator, Danny Boyle (Ciaran Hinds).

As the IRA plots its strategy, as London adopts a bunker mentality, as the hunger strike drags on to a worldwide chorus of publicity, the film’s real story comes down to this: Is any political belief so important that it is worth sacrificing the life of your son? Millions of parents, of course, vote “yes!” every time they send their children off to war. The scenario for such sacrifices seems to be hard-wired into many people, and comes under the heading of giving your life for your country.

In war, in any event, you take your chances, and try to give as good as you get. In a hunger strike, the strikers seek to bring about their own deaths. But when they lose consciousness, it is up to their parents to decide whether to allow them to die. Death by hunger takes weeks or months, during which all of the relevant morality is agonized over, priests offer advice, arguments are heard, and there is always the hope that the other side will cave in at the last minute. What it comes down to, finally, in “Some Mother’s Son,” is what it always comes down to: Hate the enemy enough, and any sacrifice is justified. See the other side as “some mother’s sons,” and you are less willing to sacrifice your own.

For Annie, there is no question. Her husband was killed by the British, and she shares her son’s convictions. Kathleen is not so sure, and it is Helen Mirren’s performance, so closely observed, with so much depth and urgency, that embodies the central questions of the movie. It is fascinating to see Kathleen’s independent intelligence shining in the midst of other characters, on both sides, who are true believers.

The movie is of course completely on the side of the IRA, but Kathleen’s dilemma succeeds in allowing a subversive notion to sneak through: Although Protestants and Catholics have been killing each other for years in Northern Ireland, can any God who permits war between sides that both seek to worship him be a God worth dying for?