There are (at least) two ways to read Alessio Della Valle’s “American Night,” an unfortunate post-modern crime drama set in and around a private art gallery owned by indecisive critic John Kaplan (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) and financed by brutally untalented artist-cum-mobster Michael Rubino (Emile Hirsch). You could interpret this movie as a weak parody of all the other decades-late “Pulp Fiction” clones that copy the most superficial qualities of Quentin Tarantino’s now-iconic 1994 movie, particularly its breezy cynicism and winking allusive-ness, but not its actual style.

One could also read “American Night” as more of a reflection than a commentary on American pop art after Andy Warhol and now Tarantino. This second take probably seems harsh, but there’s not much room for generosity in a movie where Hirsch’s kitschy villain takes his time in relating the old scorpion and frog parable, which movie buffs might remember from Orson Welles’ “Mr. Arkadin” (1955). You don’t have to already know that story to be let down with its re-presentation in “American Night,” especially since this is the kind of movie where Michael eventually shaves off his hair to reveal a scorpion tattoo on the side of his head. Is that overheated gesture supposed to be funny or dramatic? Either way, Hirsch’s fuming villain still looks sad and tacky.

The makers of “American Night” often go out of their way to let you know that they’re thinking about their story as it relates to various pop culture touchstones, like the bartender who cosplays as Kurt Cobain as photographed by Jesse Frohmann. You can tell a lot about this movie by its ostentatious three-part structure. A buzzing neon sign announces the first chapter’s title: “Art + Life.” That’s also the second chapter’s title, only now that on-screen title’s shown backwards, as if we were looking at it from the interior of John Kaplan’s art gallery. A bullet punctures the glass window that separates us from this very literal sign. We are now theoretically on the other side of the brittle looking glass that separates one kind of pop art from another. Unfortunately “American Night” often replicates without significantly expanding on a bunch of post-Tarantino clichés about individualism, free will, and the value of art in a world that’s run by shallow gangsters and doofy try-hards.

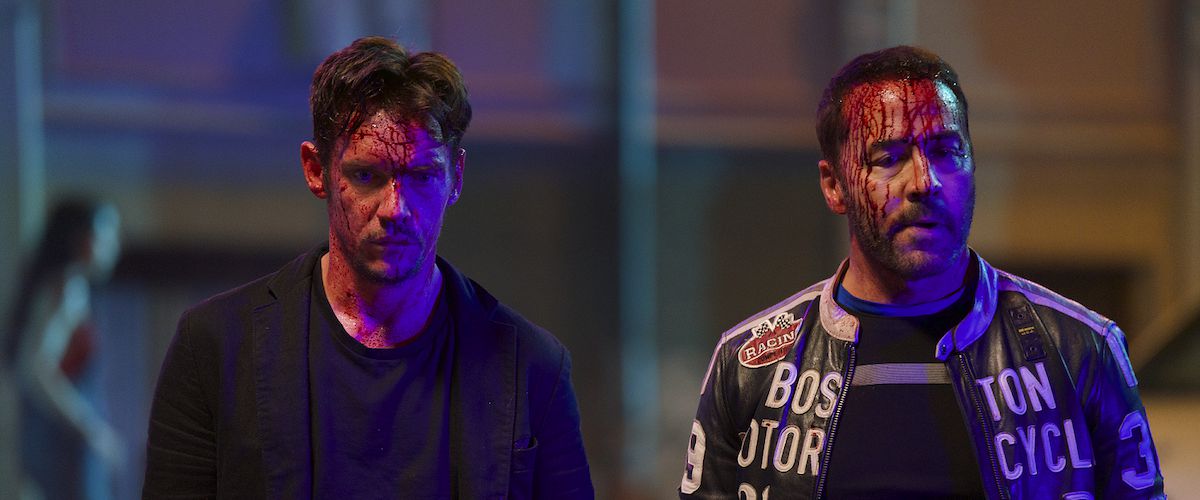

It’s often hard to know what’s wrong with “American Night” since many of its ideas are as empty and superficial as its characters. Everybody’s in debt (financially) and nobody’s fulfilled (spiritually). Kaplan’s desperate to launch his gallery, but he’s caught between two mercurial and untrustworthy mob patrons, Lord Samuel Morgan (Michael Madsen) and Rubino. Hirsch has more scenes than Madsen, so you might think that there’s more to his baddy’s insecurities. After all, Michael’s got a judgmental family (biological and mob) and some aspirational ideas about the value of art. He’s also got a laughably affected sense of style: his paintings are a mish-mash of Jackson Pollock-style dripping, real (or “real”) bullet holes created by actual guns, and empty space. What’s it all about? Not much!

There are some other noteworthy characters, particularly uncoordinated courier Shaky (Fortunato Cerlino) and unlucky stuntman Vincent (Jeremy Piven), but those guys only set up the inevitable conflict between John and Michael, both of whom are circling the same Andy Warhol painting, Michael by choice and John by happenstance.

Everybody in “American Night” is defined by their quirky behavior, which is more forgivable when it comes to minor characters like Shaky, who suffers from abrupt (and narratively contrived) fits of narcolepsy, or Vincent, who becomes obsessed with Bruce Lee’s famous “Be water” speech. John and Michael are sadly just as uninteresting, the former drifting from one love affair to another and the latter raving about the value of art despite his own work’s apparent lack of qualities: “I don’t want to hear anybody criticize my art.”

The biggest problem with evaluating a movie that’s as glib and flat as “American Night” is that there’s a lot that’s signified, but not much that’s emotionally or intellectually conveyed. What’s the functional difference between John and Michael’s respective worldviews? Sure, Michael’s paintings look silly, but John’s TED Talk-style defense of the universal necessity of art—“this is what makes us human”—isn’t much more stirring, nor are the passionless sex scenes that ostensibly distinguish Rhys Meyers’ antihero protagonist from Hirsch’s impotent antagonist.

There’s also not much of a conflict pushing them from one episodic encounter to the next, so we’re stuck watching a bunch of loud, vacant characters as they make like covered wagons in the desert, and aimlessly circle each other and their own luckless, empty lives. You can interpret “American Night” however you want, but the movie will never be more or less than what it looks like, and that ain’t much.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.