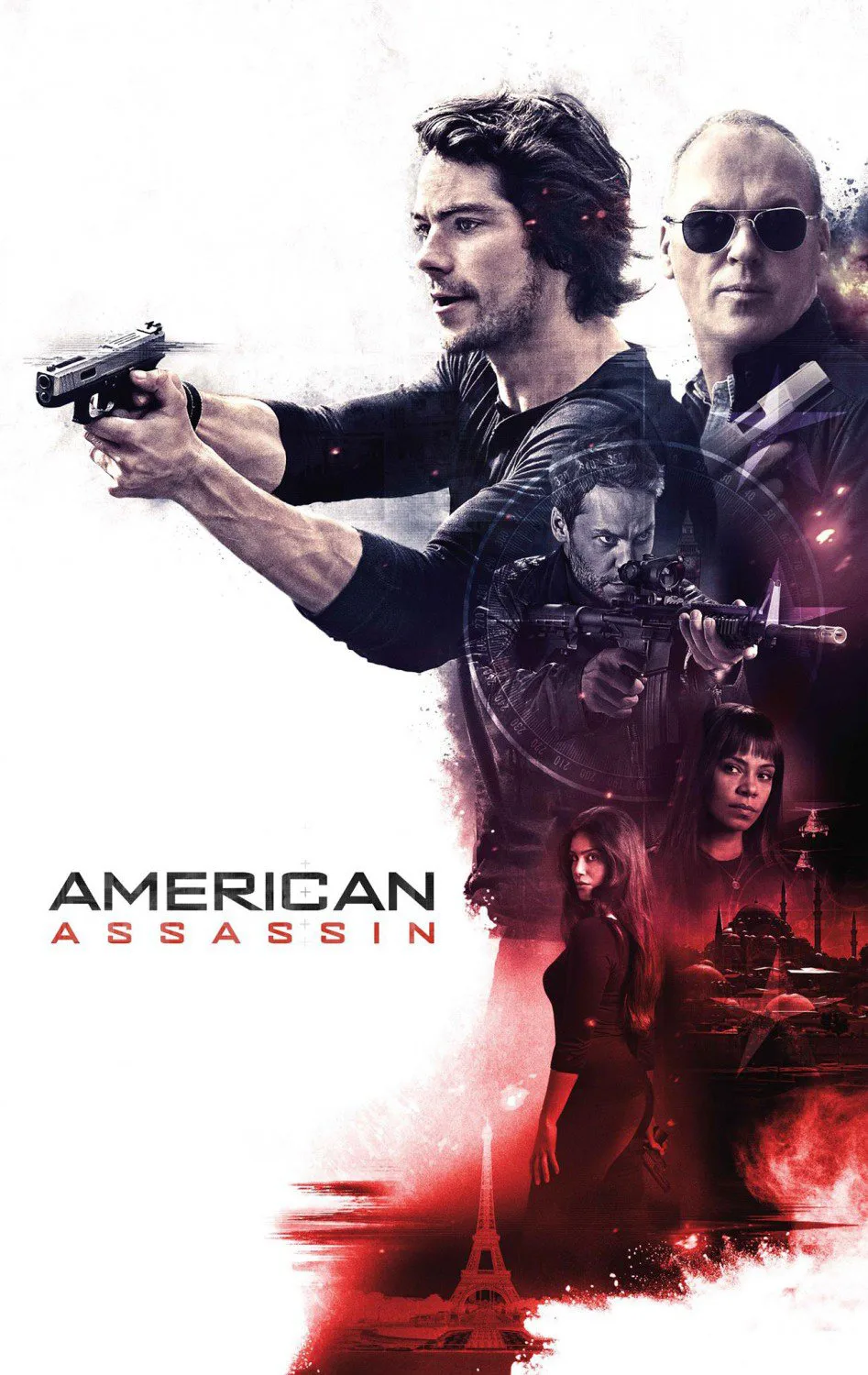

“American Assassin” is an action film, a spy thriller, a meditation on revenge, and a story about mentors and pupils, but mostly it’s a movie that loves to maim and kill people and is very good at it. Dylan O'Brien stars as Mitch Rapp, an American who loses his parents in a car wreck as a child, then fails to save his fiancee from a terrorist attack and vows to find and execute the head of the cell that ordered it. Mitch gets pulled into the CIA, where he’s trained as an assassin by Cold War veteran and former Navy S.E.A.L. Stan Hurley (Michael Keaton). Then one of Hurley’s former trainees, an arms dealer known as Ghost (Taylor Kitsch), enters the picture, and things get murky.

I don’t just mean the plot, I mean the movie’s reason for being. “American Assassin” keeps telling you that revenge poisons the soul and is generally a bad idea while serving up awesome scenes of Mitch and colleagues killing terrorists and other bad guys with guns, knives, their hands and feet, cars and trucks, and household tools used in ways that their manufacturers never envisioned. It doesn’t take long to figure out where the film’s heart lies, and it would’ve been more honest if it had embraced that impulse from the start.

Though slight and wiry, O’Brien makes an effective strong-silent action hero. He’s one of those morose outsiders who has no respect for authority but does his job so well that his superiors (including Sanaa Lathan, mostly wasted as CIA Deputy Director Irene Kennedy) keep indulging his hunches and forgiving his excesses. The tone and style are cool and assured for the first-half hour, but the movie loses its way after that. A tight, often wordless opening section lets Mitch communicate his homicidal tunnel-vision through training montages, encrypted online exchanges with terrorist recruiters, and closeups of his grief-stricken eyes.

But then the movie turns him into a stubbly, butt-kicking ingenue, defined mainly by smart-ass quips and astonishing physicality (kudos to Cuesta for keeping the camera far back enough to show that O’Brien is doing a lot of his own stunts). Although there are hints of chemistry between Mitch and a Turkish agent (Shiva Negar’s Annika) allied with Stan’s unit, the movie’s not built for that sort of thing. Mates in action films often exist to die and be avenged, and grief is more often asserted than explored. That’s the case here, too.

Mitch is a lethal bystander to his own story throughout the second hour. Vengeance comes up a lot during this section, with multiple characters enacting their own version of Mitch’s struggle, but none are well-defined enough to support an ensemble approach; you may simultaneously feel you’re getting too much of every major character but also not enough, and that the philosophical inquiry into the idea of revenge has been layered onto the screenplay to make it feel like a thoughtful statement instead of a bloody lark. Besides Mitch and Ghost, we keep meeting supporting characters who hold murderous grudges against other people, against politicians in their own government, sometimes against entire nations and ethnic groups. A band of disgruntled Iranian officials and military officers want to build a nuclear weapon with material supplied by Ghost to get revenge against the faction that drove them from power. These folks also want revenge against United States and Israel to repay old indignities (Ghost tells an Iranian high-muckety-muck that once they conclude their deal, “you can kill as many Jews as you want”).

“American Assassin” sometimes seems to want us to think it’s an earthbound film. At some points, thriller buffs might be reminded of John Frankenheimer’s bracingly nasty R-rated thrillers—in particular “Black Sunday,” which revolved around the Mossad and the PLO, and costarred Bruce Dern as a disillusioned veteran who, like Ghost, wants to punish America for disfiguring his body and spirit. There are also traces of “Day of the Jackal” and “Munich” and an obscure 1980s film called “The Amateur,” about a CIA researcher (John Savage) who convinces the agency to train him to kill so he can avenge his wife’s murder by terrorists. The script name-checks real life geopolitical rivals, terrorist groups, and political events. Besides Iran and Israel, there are references to the post-Saddam Hussein Iraqi government, Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Obama administration’s Iran deal.

But by the end, the film makes it clear that it’s disgruntled mavericks who are creating the immediate problems. This is the “one bad apple” approach to storytelling that’s meant to provide rhetorical cover for movie studios, should anyone try to protest the film or stop it from being exported to their country.

The screenplay is credited to four people: Stephen Schiff, currently a writer on FX’s “The Americans”; Michael Finch of “The Interrogation,” “The November Man” and “Hitman: Agent 47“; and Marshall Herskovitz and Ed Zwick, a team whose credits include “The Siege” (about a terrorist attack that leads to New York being quarantined) and “Jack Reacher: Never Go Back.” The director is Michael Cuesta, perhaps best known for his work on Showtime’s “Homeland,” a series that mixes geopolitical specificity and melodrama, and treats much of the Middle East as a brown menace even as it insists things are more complicated than that. The movie summons the ghosts of the Bourne saga when Ghost compares himself and Mitch to monsters that were created by the military-industrial complex to snuff out designated enemies but turned on their creators instead. But it never pulls off the magic act that made the first three Bourne films (which seem increasingly miraculous in retrospect) feel contradiction-free.

The cast does the best it can with material that too often mistakes exposition for psychology. Only Michael Keaton, who’s been acting for four decades and livens up even the worst films, manages to build an emotionally cohesive, memorable character. Is there another current star who’s better at getting the audience on his side from frame one and keeping it there no matter what? He’s a skinny leatherneck here, a business class dad’s fantasy of middle-aged machismo, and his Jimmy Cagney defiance earns the film’s only thunderous cheer (you’ll know the moment when you see it). Throughout, Keaton keeps making lines that should’ve been dead on arrival pulse with life by inserting surprising pauses into his responses to questions and glancing furtively at people and objects, so that you keep wondering if Stan knows a secret. Maybe he does know a secret: that “American Assassin” is not what it pretends to be, and both he and the audience will have a more satisfying experience if he pretends he’s in the movie that should’ve been.