“All Shall Be Well” is a picture of cruel realities. It’s a deliberate, nimble drama, one about major slights, class imbalance, and rampant homophobia.

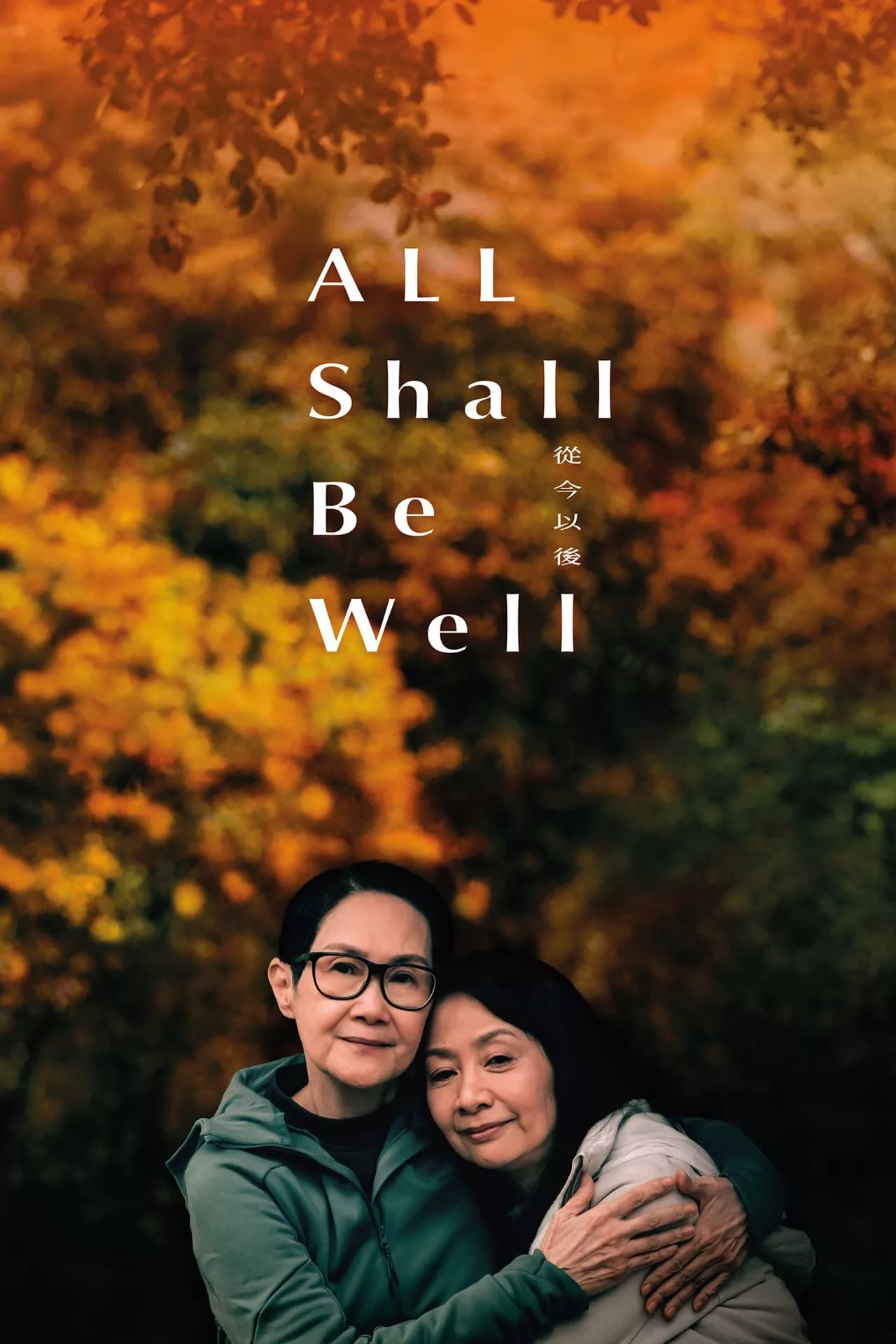

Written and directed by Ray Yeung, the film coalesces around the slipperiness of autumnal love through the eyes of Angie (Patra Au) and Pat (Lin-Lin Li). The two women have lived together for thirty years, sharing a life that includes daily hikes, trips to the market, or a flower shop owned by another lesbian couple. They fit each other wonderfully; Angie is unassuming while Pat is vibrant. The couple are critical to the health of Pat’s family, who are arriving at the couple’s home to celebrate the Mid-Autumn Festival.

The delicate balance Pat provides, however, is upset when she suddenly passes away without leaving a will. Worst yet, Pat and Angie weren’t married. We’ve all seen enough nasty interfamilial spats to know what happens next.

Yeung, thankfully, is exceptionally thoughtful in forestalling one’s expectations. The betrayal by Angie’s extended family doesn’t come quickly. Rather it occurs in a thousand tiny cuts. Pat’s brother Shing (Tai-Bo) becomes the estate’s executor, and his wife Mei (Siu Ying Hui), refers to Angie as Pat’s “best friend.” They also want her spacious apartment so they can move out of their dilapidated abode. Similarly, Angie’s nephew Victor (Chung-Hang Leung) needs the apartment to support his girlfriend. At the same time, his sister Fanny (Fish Liew) is tired of living with her children and husband above an Indian restaurant (you can feel the xenophobia in her loathing of the place’s smell).

In a lesser filmmaker’s hands, these people would simply be nasty, easy-to-hate scoundrels. But Yeung is smart enough to zig when you expect him to zag. While Pat and Angie were making money as factory owners, Shing and Mei were losing their restaurant. The foreclosure forced the former to work nights as a parking attendant and the latter to clean hotel rooms. Yeung also backgrounds their struggle and the difficulties Victory and Fanny face against the present housing crisis in Hong Kong, where the film takes place, forcing many into unhealthy living conditions without any hope of escaping. It’s telling, for instance, that Victor is shown a rentable apartment that amounts to a closet; in another one, Fanny’s husband puts up a sign to cover a rat hole. When an opportunity arises to seize the type of generational wealth that Angie’s apartment provides, you can somewhat understand why and how her relatives would become vicious toward her.

Those systemic issues, of course, do not absolve them of their nastiness. The film doesn’t make such sweeping validations, either. There is a continual erasure of Angie by this family that is damn near unforgivable. Before long, they wield the legal system, which clearly doesn’t protect same-sex couples—Pat and Angie would’ve needed to be married overseas to be lawfully recognized—to undermine Angie’s right to live, to love, and to memorialize.

Through it all, Angie bears an acute anguish in her loneliness. The camera follows suit. Where many would lean into close-ups, working to pull every ounce of emotion from the actor’s face, Yeung and his cinematographer Ming-Kai Leung allow their lens to remain distant from Angie through much of the film. The dimmed lighting and neutral color palette further suggest the character’s sense of alienation. Au is a fantastic actress, too, who doesn’t solely rely on a tear or a grimace to connect the character’s pain to the audience. She gives a fully felt physical performance. With each slight thrown by members of her extended family, she bends lower. She is so broken, so physically and emotionally bent, that one can see her fight leaving from her skin.

This film is so patient that it’s disappointing to see it take such an easy path to re-spark Angie’s fight. The slight twist allows Angie to feel loved and remembered, which, admittedly, is an imperative emotion to leave the viewer with. The emotional message, nevertheless, is a bit too blunt and only really lands via Au’s wellspring of pathos. That tiny misstep doesn’t undo much, if any, of what’s wonderful about “All Shall Be Well.” This is a film whose intricacies and ruminations hold you dear, tenderly whispering that “this too shall pass.”