In “Father of My Children” (2009), Mia Hansen-Løve’s second feature-length film, a successful film producer (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) finds himself in deep financial trouble. He keeps it a secret from his family. He faces utter ruination. The movie is a psychological study, dramatic without making a point of it, with no sense of push in Hansen-Løve’s approach. “Father of My Children” was the first of her films to get international traction, and it’s a powerful watch, even with repeat viewings. The filmmaking is so confident it’s hard to believe Hansen-Løve was only 27 years old when she wrote and directed it.

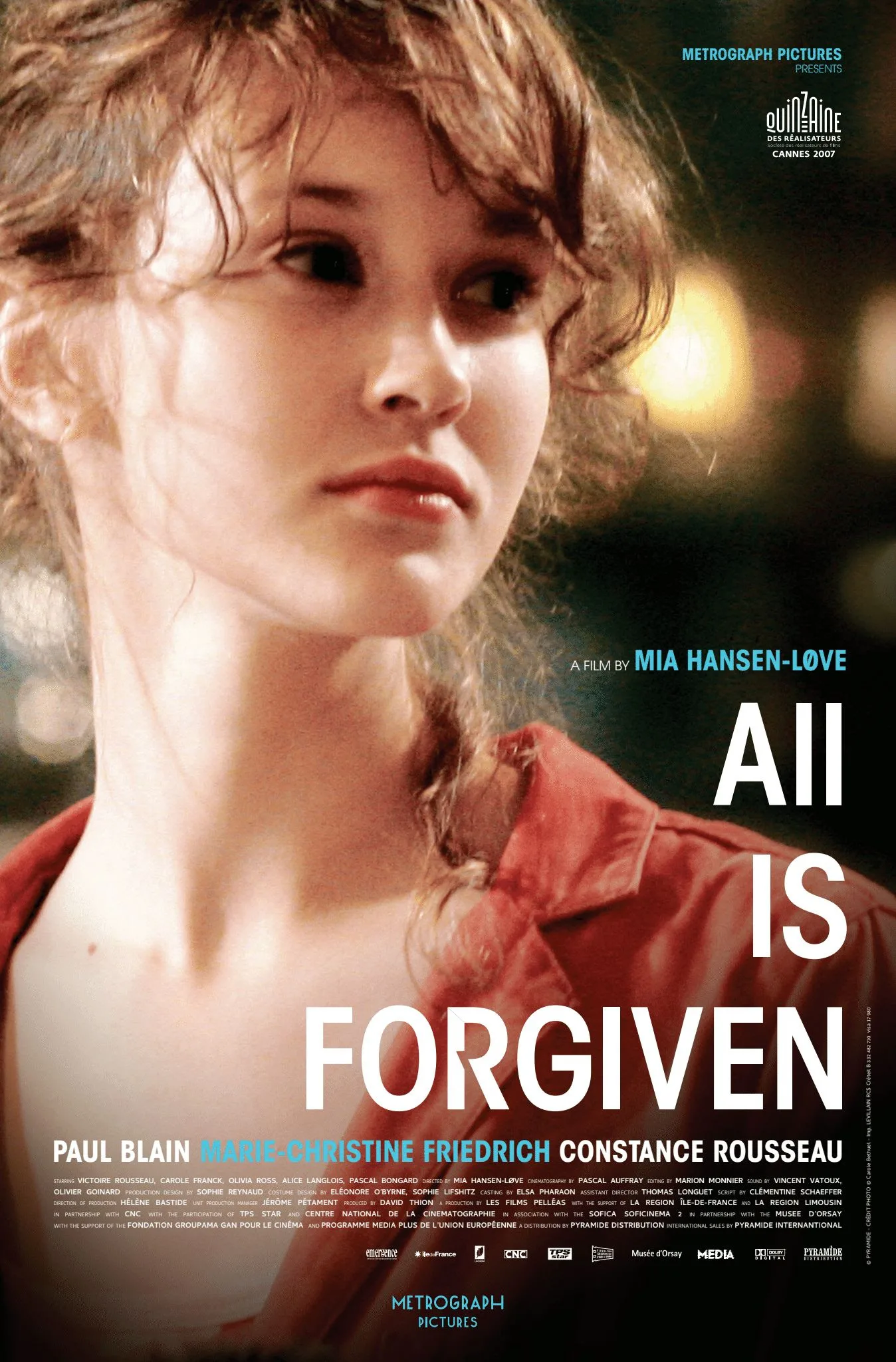

Before “Father of My Children” was Hansen-Løve’s directorial debut, 2007’s “All is Forgiven,” made when she was only 25 years old. “All is Forgiven” was never released in the United States until now. In the last decade, with such movies as “Eden,” “Things to Come,” “Maya,” and this year’s “Bergman Island,” Hansen-Løve has become one of the most exciting filmmakers working today. “All is Forgiven” allows us to see her at the very beginning of this journey, and it’s thrilling to witness her style and artistic tendencies, already in operation and at full form from the start.

The subject matter of Hansen-Løve’s filmography is diverse (young love, divorce, suicide, club music), but her main subject is the passage of time. Many directors focus on time (Richard Linklater explicitly plays around with it in “Boyhood” and the “Before” trilogy), but Hansen-Løve’s interest manifests itself in a singular way. She looks at time the way a novelist does. A novelist can linger for 20 pages on the minutia of a single day in the life of a family, and then leap forward into the next generation a page later. Films rarely exhibit this freedom. Aristotelian unities are irrelevant to Hansen-Løve. She doesn’t use flashbacks, and her films always move forward, but she allows time to stretch out or contract, the audience leapfrogging over intervening years.

“All is Forgiven” starts in Vienna in 1995 and ends in Paris in 2007, and centers on the experiences of a family unit: Victor (Paul Blain), his partner Annette (Marie-Christine Friedrich), and their six-year-old daughter Pamela (Victoire Rousseau). Victor is French, but Annette is Austrian, and for reasons that only become clear over a long passage of time, they have chosen Austria as their home base. Or, Annette has chosen, because Victor makes a lifestyle out of not choosing anything.

Victor is charismatic, with a gleam in his eye; when he looks at people he seems open and curious about them. The expression is almost “come-hither,” in the classic flirtatious sense. This is a fascinating choice, although it doesn’t seem like a conscious one on Victor’s part (but maybe it is, maybe by projecting “come hither” at everybody in his vicinity Victor avoids facing the void within). These multiple possibilities are Hansen-Løve’s wheelhouse, and it’s present even at the young age of 25. Her camera obsesses over Blain’s face, his responses, his unspoken thoughts, his observational outsider stance. Victor’s come-hither-ness is an undercurrent, a default emotional position, and it’s never explained, or even really commented on. We are just seeing how this guy operates, how he navigates the world.

Whatever charm Victor may have no longer works on Annette, especially since Victor seems determined to not do anything with his life. He sits around all day. He speaks vaguely of “writing.” He does drugs. He is a compulsive underachiever. Annette says, frustrated, “Why do you want everyone to think you’re a loser?” When the family unit moves back to Paris, Victor’s drug use escalates. He is violent with Annette. Young Pamela witnesses all of it. Annette kicks him out, and he holes up with another drug addict. Victor talks about his anxiety and malaise to his sister Martine (Carole Franck), but does so with that little spark of charisma still in his eyes. Is he anxious for real? Or is he just lazy? Is this just what addicts do? He loves Annette and Pamela. What is going on with this guy? In a 2016 interview with Indiewire, Hansen-Løve said, “For me, making films is about questions, not about the answers. I guess that if I would have the answers, I wouldn’t have to write the film at all.”

Halfway through, there is an alarming title card: “11 Years Later.” (The other title cards are more manageable: “Back in Paris,” “One Month Later,” etc.) With no advance notice, “All is Forgiven” jumps forward over a decade. Annette and Victor are no longer together, Annette is remarried, and Pamela (now played by Constance Rousseau, the actual older sister of Victoire) is a college student with only vague memories of her father. Martine—whom Pamela doesn’t remember—reaches out, hoping to engineer a family reunion. Victor is in Paris. He is not “sick” like he used to be. He wants a relationship with his daughter.

As with her later films, particularly “Eden” which takes place over a 20-year time frame, Hansen-Løve is interested in time, but is disinterested in portraying the effect of time’s passing, via old-age makeup, or even slight changes in the characters’ appearance. Annette looks more severe than she did in the first half, but nothing has been done to “age” her. Victor looks exactly the same. However, Pamela is now played by a different actress. This creates an eerie effect of Victor and Annette being trapped in time, stuck, while Pamela moves forward, still transforming. Hansen-Løve’s refusal to concern herself with physical details (greying hair, wrinkles, jowls, etc.) opens up worlds of interpretive possibilities.

How the Victor-Pamela reunion goes will be familiar to anyone who has known and loved a drug addict, but the moment-by-moment experience of it in “All is Forgiven” is unexpected. Hansen-Løve often includes scenes left out by other directors: scenes of people walking to and from places, those in between moments normally excised from film because we don’t need to know every step a person takes to get from A to B. But Hansen-Løve cares about the in-between, the spaces between things, people, locations, dialogue. Here, there’s a long scene showing Pamela walking back to her grandparents’ house, across fields, over hills, through the woods. It’s Pamela getting from one location to the other. Life is lived in the moment in between too. Watch for these scenes in Hansen-Løve’s films. They are everywhere. Her style is very patient; she is in no rush to get to the next thing. It’s one of the reasons why “All is Forgiven,” a simpler story than, say, “Eden” or “Things to Come,” has such resonance. It’s one of those rare films where the title has real meaning, one that grows in power the moment the credits roll.

What is it about Hansen-Løve’s work that is so appealing? I suppose it’s different for different people. For me, her work evokes what John Keats called “negative capability,” extremely rare in humans (then, now, or ever). According to Keats, negative capability is when “man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” It’s common to talk about how polarized our world is right now. Yes. But every era has its polarizations, and human beings, perhaps, are drawn to stark binaries. But what’s happening in between—all those “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts,” all those walks home, or walks to work, or walks through a park with a father you’ve never known—that’s where all the good stuff lies. That’s where art lies. To recognize that at the age of 25, as Hansen-Løve clearly did, is really something.

Now playing theatrically and digitally exclusively at the Metrograph, with a nationwide expansion on November 19th.