A sweeping romance set in the Caspian Sea region around the time of World War I, Asif Kapadia’s “Ali & Nino” is the kind of lush historical drama that Hollywood might have made in the 1930s but these days unsurprisingly owes its existence to foreign producers and, most especially, a renowned literary source.

Though it may be unfamiliar even to many Americans up on their 20th century world literature, the book behind the movie caused Paul Theroux to exclaim: “This wonderful novel—beautifully constructed, vivid and persuasive, a love story at once exotic and familiar—is living proof that art is indestructible and transcendent.”

First published in Vienna in German in 1937, “Ali & Nino” is credited to Kurban Said, a pseudonym. While it has continued to accrue fame since it was rediscovered after World War II, the debate over its author’s identity has been the subject of elaborate debates and arguments. Currently, most opinion attributes its publication to two people: Lev Nussimbaum, who was born a Jew in Russia, spent most of his childhood in Baku, then fled the Bolshevik invasion to Germany, converted to Islam and wrote under the name Essad Bey; his putative collaborator was Austrian baroness Elfriede Ehrenfels, who may or may not have been involved in the book’s writing but was able to copyright it with the German authorities, something Nussimbaum was denied due to his Jewish background.

While many efforts to bring the novel to the screen have been bruited over the decades, this one was mounted by a British production company with a screenplay by playwright Christopher Hampton (“Dangerous Liaisons”), an English director and lead actors hailing from Israel and Spain. In other words, it is obviously a different movie than would have been the case had it been made by filmmakers, writers and actors from the cultures it depicts, especially Azerbaijan but also Georgia (the former Soviet republic), Armenia and Iran.

That’s an important distinction for a book that Theroux calls “a bravura display of passionate ethnography,” one that he likens to Madame Bovary, Moby-Dick and Ulysses for the lavish detail it summons in describing a culture unfamiliar to many in the West. While Hampton and his collaborators have tried to weave some of this detail, as well as authentic settings and landscapes, into their rendition of Said’s tale, they have also understandably downplayed the book’s ethnographic aspect in favor of its love story.

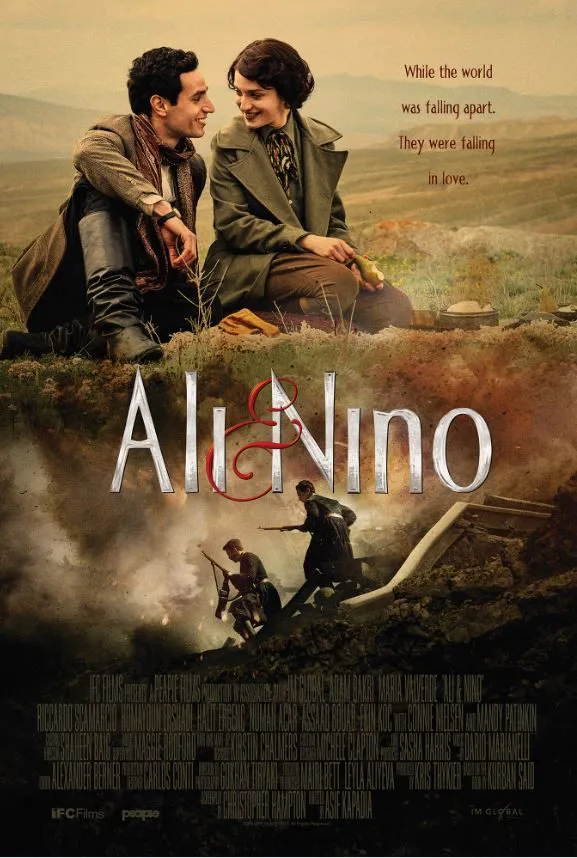

Yet even there, culture, religion and the historical backdrop are important. Ali Khan Shirvanshir (Adam Bakri) is a young Muslim who hails from a traditional family but has become acquainted with Western ways through attending a Russian high school in Baku. When he meets Nino (María Valverde), a Christian princess from Tbilisi in Georgia, there’s an instant romantic spark. But the cross-cultural difficulties are compounded by the arrival of World War I. Though Ali’s father approves the marriage his son desires, Nino’s dad wants it to await the end of the war, which he assumes will be brief.

Into this garden of complications, a serpent creeps. Malik (Riccardo Scamarcio), an Armenian Christian, offers to make the couple’s case to Nino’s parents, but, secretly desiring the girl himself, he abducts her and makes for Russia. Ali gives chase and kills his false friend. Since the death will ignite a blood feud, Ali is obliged to flee to the mountains of Dagestan. When Nino finds him there, the couple weds and then enjoys an idyllic retreat from the world.

Their blissful isolation ends when events compel them to return to Baku. With the city threatened by the incursion of deserting Imperial troops, Ali elects to fight in defense of his homeland while Nino works as a nurse. The chaos and danger mount, though, so that, after announcing her pregnancy, Nino is spirited away to Persia, where she leads a cloistered, unhappy life watched over by a eunuch, and gives birth to a daughter.

Ali retrieves his new family and returns them to Baku after the world war ends and Azerbaijan gains its independence for the first time in centuries. It’s a moment of nationalist pride and jubilation, with Azeris assuring each other that the Treaty of Versailles will guarantee their autonomy. They have only failed to foresee the effects of the Russian Revolution. Within months, Bolshevik armies are moving to invade the fledgling republic, an incursion that will seal the fates of Ali and Nino.

In Kapadia’s film, the passionate love story at the heart of Said’s novel anchors a drama that also surveys a fascinating slice of history, one with ongoing geopolitical relevance (at the time of the story, the Baku area was producing half of the world’s oil, which made it coveted by several empires and corporations). In various ways, the tale may remind viewers of Doctor Zhivago, another celebrated romantic novel set during the same period. Yet the movie it inspired was a much grander affair than “Ali and Nino,” truly epic in its sweep and as plush in its mounting as any studio movie of its era.

Plus, it had major international stars and, above all, David Lean as director. “Ali and Nino” is a much lesser film in every respect. And while a huge difference in budget may account for much of that, there’s also the matter of the levels of talent involved. Kapadia is known for the truly terrific documentaries “Senna” and “Amy,” films that nevertheless don’t seem to have imbued him with the skills to coax great performances out of little-known actors. While Bakri and Valverde are nice looking performers, too much of their time on-screen consists of gazing at each other with silly, smitten smiles—a weakness that undermines the powerful drama that surrounds them.