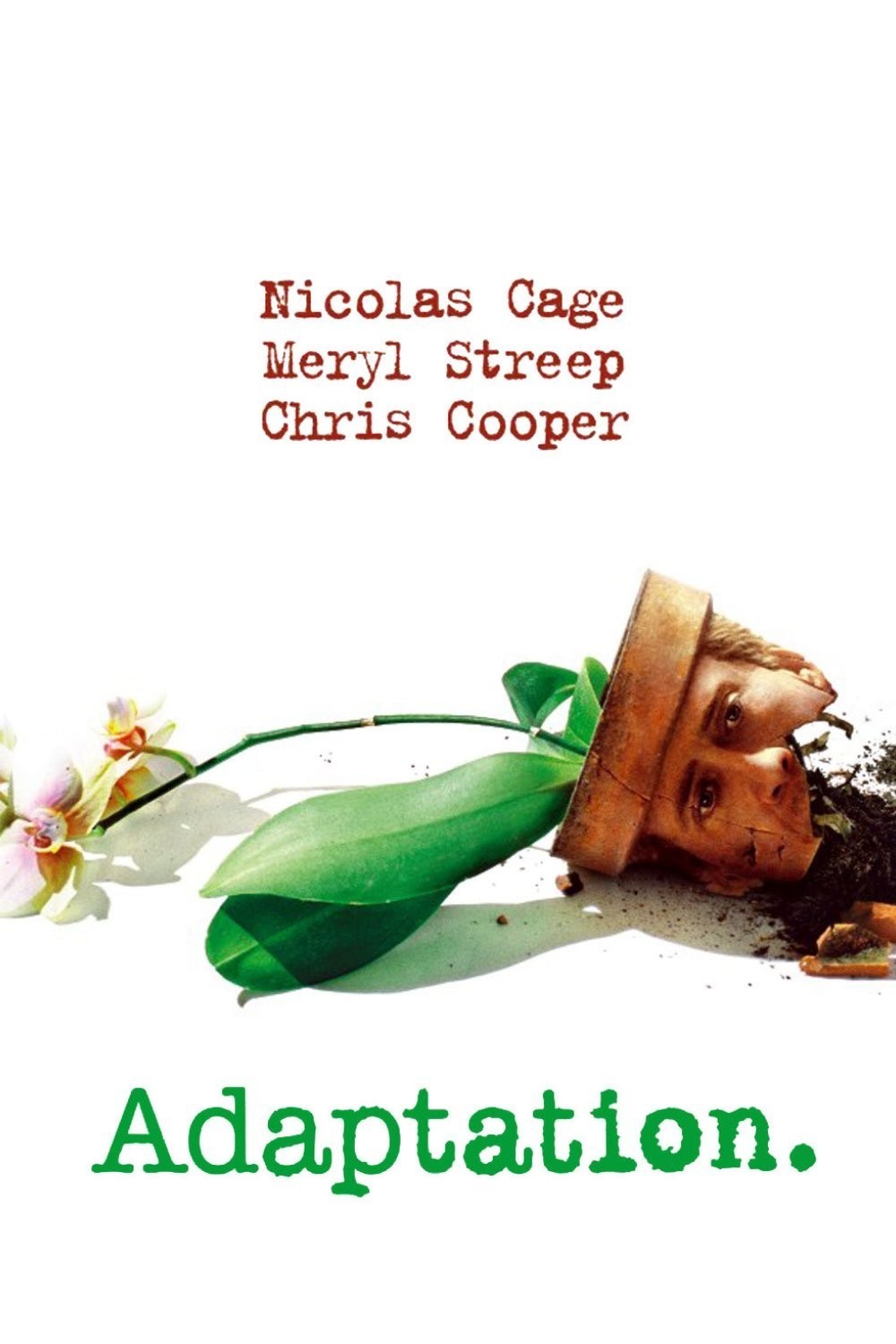

What a bewilderingly brilliant and entertaining movie this is–a confounding story about orchid thieves and screenwriters, elegant New Yorkers and scruffy swamp rats, truth and fiction. “Adaptation” is a movie that leaves you breathless with curiosity, as it teases itself with the directions it might take. To watch the film is to be actively involved in the challenge of its creation.

It begins with a book titled The Orchid Thief, based on a New Yorker article by Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep). She writes about a Florida orchid fancier named John Laroche (Chris Cooper), who is the latest in a long history of men so obsessed by orchids that they would steal and kill for them. Laroche is a con man who believes he has found a foolproof way to poach orchids from protected Florida Everglades; since they were ancestral Indian lands, he will hire Indians who can pick the orchids with impunity.

Now that story might make a movie, but it’s not the story of “Adaptation.” As the film opens, a screenwriter named Charlie Kaufman (Nicolas Cage) has been hired to adapt the book, and is stuck. There is so much about orchids in the book, and no obvious dramatic story line. Having penetrated halfway into the book myself, I understood his problem: It’s a great story, but is it a movie? Charlie is distraught. His producer, Valerie (Tilda Swinton), is on his case. Where is the first draft? He hardly has a first page. He relates his agony in voiceover, and anyone who has ever tried to write will understand his system of rewards and punishments: Should he wait until he has written a page to eat the muffin, or …

Charlie has a brother named Donald (also played by Cage). Donald lacks Charlie’s ethics, his taste, his intelligence. He cheerfully admits that all he wants to do is write a potboiler and get rich. He attends the screenwriting seminars of Robert McKee (Brian Cox), who breaks down movie classics, sucks the marrow from their bones and urges students to copy the formula. At a moment when Charlie is suicidal with frustration, Donald triumphantly announces he has sold a screenplay for a million dollars.

What is Charlie to do? To complicate matters, he has developed a fixation, even a crush, on Susan Orlean. He journeys to New York, shadows her, is too shy to meet her. She in turn goes to Florida to interview Laroche, who smells and smokes and has missing front teeth, but whose passion makes him … interesting.

And now my plot description will end, as I assure you I have not even hinted at the diabolical developments still to come. “Adaptation” is some kind of a filmmaking miracle, a film that is at one and the same time (a) the story of a movie being made, (b) the story of orchid thievery and criminal conspiracies, and (c) a deceptive combination of fiction and real life. The movie has been directed by Spike Jonze, who with Charlie Kaufman as writer made “Being John Malkovich,” the best film of 1999. If you saw that film, you will (a) know what to expect this time, and (b) be wrong in countless ways.

There are real people in this film who are really real, like Malkovich, Jonze, John Cusack and Catherine Keener, playing themselves. People who are real but are played by actors, like Susan Orlean, Robert McKee, John Laroche and Charlie Kaufman. People who are apparently not real, like Donald Kaufman, despite the fact that he shares the screenplay credit. There are times when we are watching more or less exactly what must (or could) have happened, and then a time when the film seems to jump the rails and head straight for the swamps of McKee’s theories.

During all of its dazzling twists and turns, the movie remains consistently fascinating not just because of the direction and writing, but because of the lighthearted darkness of the performances. Chris Cooper plays a con man of extraordinary intelligence, who is attractive to a sophisticated New Yorker because he is so intensely himself in a world where few people are anybody. Nicolas Cage, as the twins, gets so deeply inside their opposite characters that we can always tell them apart even though he uses no tricks of makeup or hair. His narration creates the desperate agony of a man so smart he understands his problems intimately, yet so neurotic he is captive to them.

Now as for Meryl Streep, well, it helps to know (since she plays in so many serious films) that in her private life she is one of the merriest of women, because here she is able to begin as a studious New Yorker author and end as, more or less, Katharine Hepburn in “The African Queen.” I sat up during this movie. I leaned forward. I was completely engaged. It toyed with me, tricked me, played straight with me, then tricked me about that. Its characters are colorful because they care so intensely; they are more interested in their obsessions than they are in the movie, if you see what I mean. And all the time, uncoiling beneath the surface of the film, is the audacious surprise of the last 20 minutes, in which–well, to say the movie’s ending works on more than one level is not to imply it works on only two.