“Sometimes I just wish I was a whole other person,” says Pearl Kantrowitz, who is the subject, if not precisely the heroine, of “A Walk on the Moon.” It is the summer of 1969, and Pearl and her husband, Marty, have taken a bungalow in a Catskills resort. Pearl spends the week with their teenage daughter, their younger son and her mother-in-law. Marty drives up from the city on the weekends.

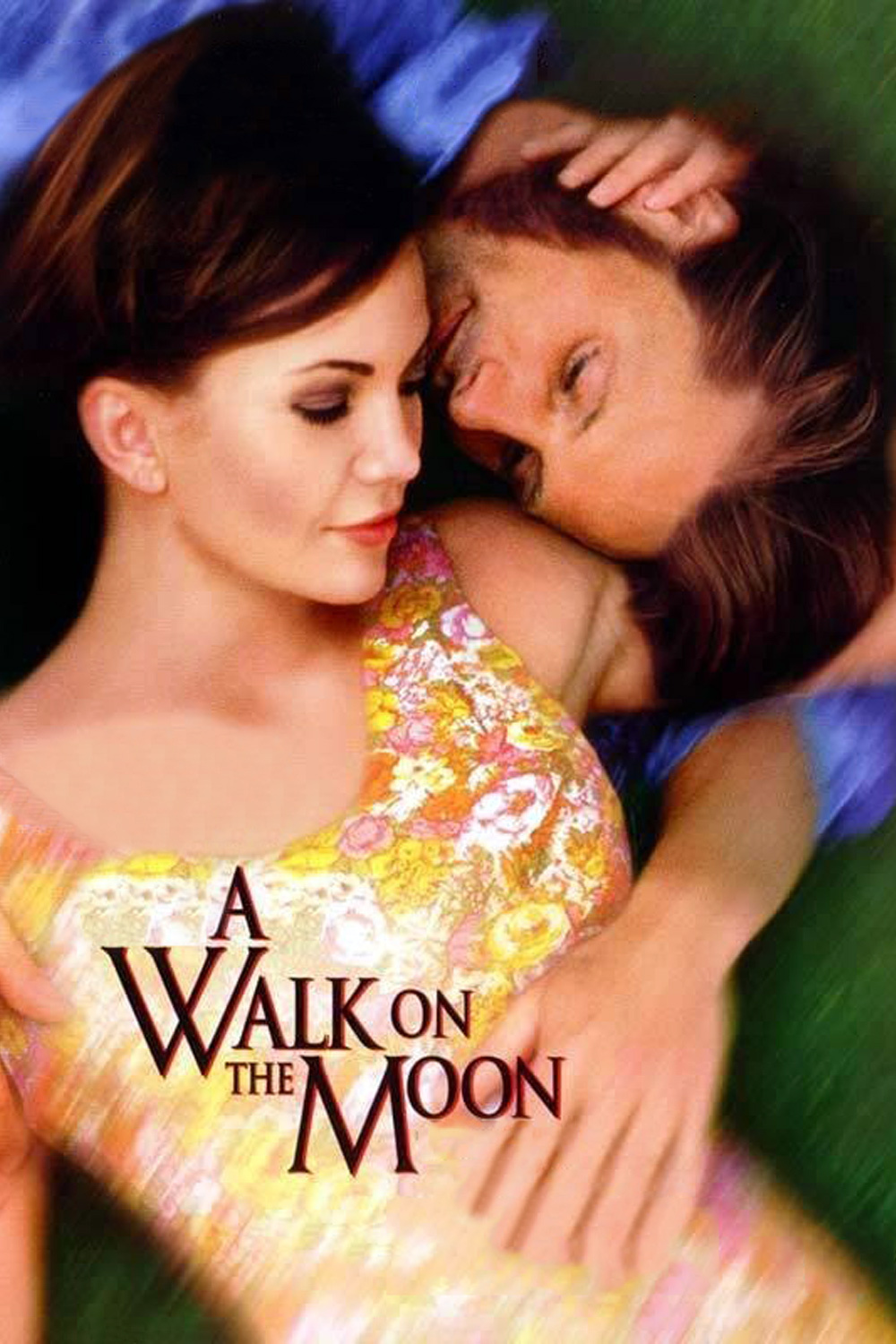

The summer of 1969 is, of course, the summer of Woodstock, which is being held nearby. And Pearl (Diane Lane), who was married at a very early age to the only man she ever slept with, feels trapped in the stodgy domesticity of the resort–where wives and families are aired and sunned, while the man labors in town. She doesn’t know it, but she’s ripe for the Blouse Man (Viggo Mortensen).

The Blouse Man drives a truck from resort to resort. The side of the truck opens out into a retail store, with marked-down prices on blouses and accessories. Funny, but he doesn’t look like a Blouse Man: With his long hair and chiseled features, he looks more like a cross between a hippie and the hero on the cover of a paperback romance. He senses quickly that Pearl is shopping for more than blouses, and offers her a free tie-dyed T-shirt, and his phone number. The T-shirt is crucial, symbolizing a time when women of Pearl’s age were in the throes of the Sexual Revolution. Soon Pearl is using the phone number. “I wonder,” she asks the Blouse Man, “if you had plans for watching the Moon Walk?” “A Walk on the Moon” is one small step for the Blouse Man, a giant leap for Pearl Kantrowitz. In the arms of the Blouse Man, she experiences sexual passion and a taste of freedom, and soon they’re skinny-dipping just like the hippies at Woodstock. The festival indeed exudes a siren call, and Pearl, like a teenage girl slipping out of the house for a concert, finally sneaks off to attend it with the Blouse Man. Marty (Liev Schreiber), meanwhile, is stuck in the Woodstock traffic jam. And their daughter Alison (Anna Paquin), who has gotten her period and her first boyfriend more or less simultaneously, is at Woodstock, too–where she sees her mother.

The movie is a memory of a time and place now largely gone (these days Pearl and Marty would be more likely to take the family to Disney World, or Hawaii). It evokes the heady feelings of 1969, when rock was mistaken for revolution. To be near Woodstock and in heat with a long-haired god, but not be able to go there, is a Dantean punishment. But the movie also has thoughts about the nature of freedom and responsibility. “Do you think you’re the only one whose dreams didn’t come true?” asks Marty, whose early marriage meant he became a TV repairman instead of a college graduate.

Watching the gathering clouds over the marriage, Pearl’s mother-in-law, Lilian (Tovah Feldshuh), sees all and understands much. If Pearl is not an entirely sympathetic character, Lilian Kantrowitz is a saint. She calls her son to warn him of trouble, she watches silently as Pearl defiantly leaves the house, and perhaps she understands Pearl’s fear of being trapped in a life lived as an accessory to a man.

So the underlying strength of the story is there. Unfortunately, the casting and some of the romantic scenes sabotage it. Liev Schreiber is a good actor, and I have admired him in many movies, but put him beside Viggo Mortensen and the Blouse Man wins; you can hardly blame Pearl for surrendering. (I am reminded of a TV news interview about that movie where Demi Moore was offered $1 million to sleep with Robert Redford. “Would you sleep with Robert Redford for a million dollars?” a woman in a mall was asked. She replied: “I’d sleep with him for 50 cents.”) The movie’s problem is that it loads the casting in a way that tilts the movie in the direction of a Harlequin romance. Mortensen looks like one of those long-haired, bare-chested, muscular buccaneers on the covers of the paperbacks; all he needs is a gothic tower behind him, with one light in a window. The movie exhibits almost unseemly haste in speeding Pearl and the Blouse Man toward lovemaking, and then lingers over their sex scenes as if they were an end in themselves, and not a transgression in a larger story. As Pearl and the Blouse Man cavort naked under a waterfall, the movie forgets its ethical questions and becomes soft-core lust.

Then, alas, there is the reckoning. We know sooner or later there will be anger and recrimination, self-revelation and confession, acceptance and resolve, wasp attacks and rescues. We’ve enjoyed those sex scenes, and now, like Pearl, we have to pay. Somewhere in the midst of the dramaturgy is a fine performance by Anna Paquin (from “The Piano”) as a teenage girl struggling with new ideas and raging hormones. Every time I saw her character onscreen, I thought: There’s the real story.