I cannot recommend “A Time for Dying,” a 1969 Western that is, amazingly, having its Midwest premiere 13 years later at the Film Center. The movie is too slight, too flat and too unintentionally ludicrous. What I can recommend is the strange experience of seeing it. This lost film, an underground legend for more than a decade, combines immaturity and cynicism in such a weird way that there is not another film like it. To see it is to see all the conventions of the Western crumble to pieces.

The movie was made by Budd Boetticher, the legendary Chicago-born writer and director of B Westerns and crime films. It concludes the Film Center’s three-week tribute to Boetticher’s career, which centered around a series of eight Westerns which all starred Randolph Scott and which all told about the same story; in music, they’d be called variations on a theme.

Boetticher’s career lost momentum in 1960. He spent the early years of the decade making a documentary about a bullfighter, but did not make another feature until “A Time for Dying,” in 1969. It’s said he made this film as a favor to his friend Audie Murphy, the actor and war hero.

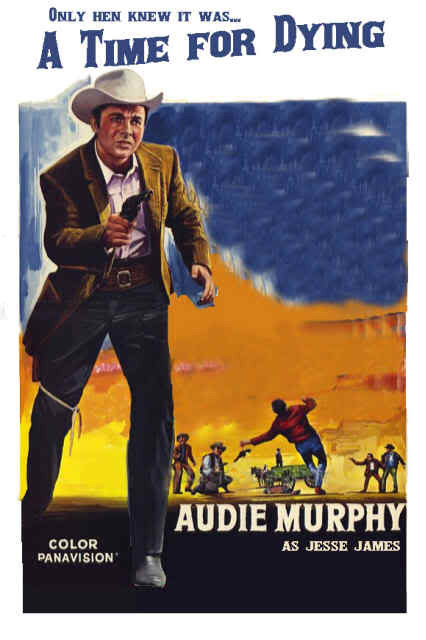

It’s likely the favor worked both ways, since Boetticher was more or less unemployable when Murphy decided to produce this film and star in it as Jesse James. Murphy died as the production was being completed, and rights to the film were tied up in litigation over his estate until quite recently. Now here it Is.

And “A Time for Dying” Is the damnedest, confoundingest Western you can imagine. For one thing, Boetticher seems to want it to took like a phony, one-dimensional formula Western, shot in the desert and in an obviously artificial’ town made of flat sets and a few Interiors.

This movie has the visual texture of a Gene Autry epic, and that may have been a deliberate choice, since its cinematographer was Lucien Ballard, who from 1967 to 1970 (before and after “A Time for Dying”) photographed the realistic-looking Westerns “Hour of the Gun,” “Will Penny,” “The Wild Bunch,” “True Grit” (1969) and “The Ballad of Cable Hogue.”

“A Time for Dying” opens with a kid who wants to be a gunfighter. A lot of Westerns do. But this kid (played by Richard Lapp) is the goofiest kid I’ve ever seen in a Western. He has a squeaky voice, a nervous smile, a funny: haircut, and he overplays his good manners into an affectation.

He rides into a town run by a drunken, hanging judge (Victor Jory as Judge Roy Bean). He discovers that a young lady (Anne Randall) is due on the evening stagecoach and does not know she’s being brought to town to be a prostitute at Mamie’s Place.

He rescues the girl from a drunken mob, unwisely books her into the local, hotel, stands guard at her door, and is nevertheless arrested for immorality. Judge Bean makes things right by marrying the couple on the spot. Incredibly, they accept this fate, and remain married throughout the picture. They never consummate the relationship, however, preferring to spend time wandering through the sagebrush while the kid brags about how he’s gonna become a bounty hunter, kill Jesse James and collect the award money.

The end of the film has to be seen to be believed. I will not reveal it. But observe, if you see the film, how completely Boetticher rejects all the conventional solutions to his material and goes for an ending which is cruel in its utter, unforgiving cynicism. He probably made the right choice.

“A Time for Dying,” played straight, would have been not a B Western but a D-minus. Boetticher’s conclusion, however, turns the movie Into a bizarre meditation on the Western myths of the gunfighter, the “kid,” the prostitute, death and redeeming your self-respect.