There is a moment in “True Grit” when John Wayne and four or five bad guys confront each other across a mountain meadow. The situation is quite clear: Someone will have to back up or die.

Director Henry Hathaway pulls his telephoto lens high up in the sky, and we see the meadow isolated there, dreamlike and fantastic. And then we’re back down on the ground, and with a growl Wayne puts his horse’s reins in his teeth, takes his rifle in one of his hands and a six-shooter in the other and charges those bad guys with all barrels blazing. As a scene, it is not meant to be taken seriously.

The night I saw a sneak preview, the audience laughed and even applauded. This was the essence of Wayne, the distillation. This was the moment when you finally realized how much Wayne had come to mean to you. I have on occasion disliked his movies, most particularly “The Green Berets.” But Wayne has a way of surmounting even bad movies, and in 40 years he has also made a great many good ones. In the early ones, like “The Quiet Man” or “The Long Voyage Home,” he was simply an actor or simply a star. But long before many of us were born, John Ford began to sculpture the actor and the star into the presence. Today there is no actor in movies who is more an archetype.

One of the glories of “True Grit” is that it recognizes Wayne’s special presence. It was not directed by Ford (who in any event probably couldn’t have been objective enough about Wayne), but it was directed by another old Western hand, Hathaway, who has made the movie of his lifetime and given us a masterpiece. This is the sort of film you call a movie, instead of the kind of movie you call a film.

It is one of the most delightful, joyous scary movies of all time. It goes on the list with “National Velvet” and “Robin Hood” and “The African Queen” and “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” and “Gunga Din.” It is not a work of art, but it wouldn’t be nearly as good if it were. Instead, it is the Western you should see if you only see one Western every three years (an act of denial I cannot quite comprehend in any case).

It is based faithfully on Charles Portis’ novel, and it tells the story of Mattie Ross from near Dardanelle, in Yell County. One day her father rides off to the city and is murdered by a cowardly snake. Mattie (played with the freshness of sweet cream by Kim Darby) rides to town to hire somebody to go into the Indian Territory and capture the scoundrel.

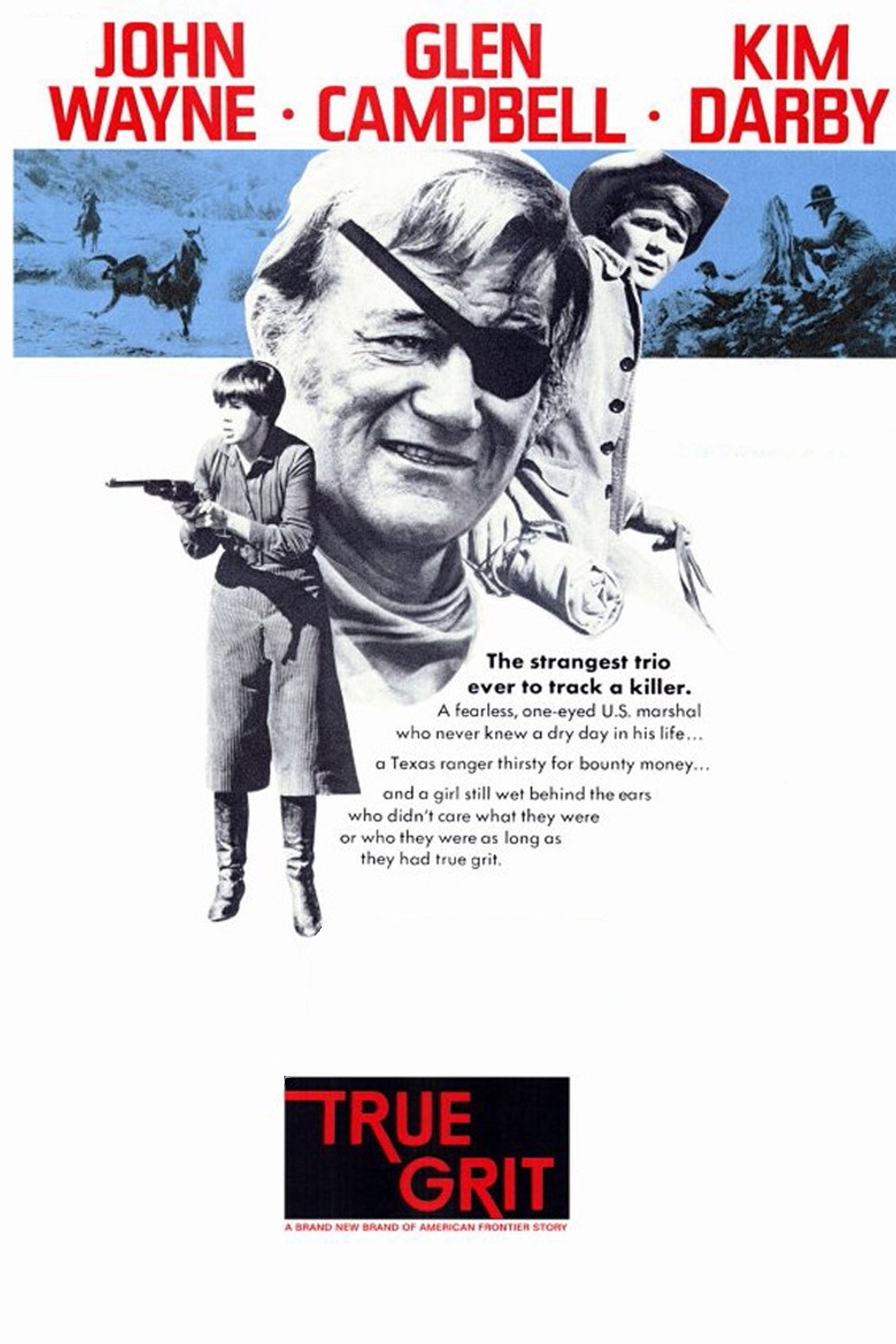

She strikes a bargain with U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn (Wayne), who is a one-eyed, unwashed, sandpapered, roughshod, fat old rascal with a heart of gold well-covered by a hide of leather. Then a Texas Ranger (Glen Campbell) gets into the act when he turns up and claims he has a reward for the killer (who also, it appears, plugged a state senator in Texas). “It is a small reward,” the ranger explains, “but he was not a large senator.”

After two horse-trading scenes in which Mattie outtalks the horse trader and drives him to distraction, the three set out into Indian Territory. Rooster and the ranger can’t get rid of Mattie so she comes along. And we embark on a glorious adventure not far removed from Huck Finn’s trip down the Mississippi, for this is also an American odyssey. Portis wrote his dialog in a formal, enchantingly archaic style that has been retained in Marguerite Roberts’ screenplay.

Campbell, who needs some acting practice, finds it difficult to make the dialog convincing but Hathaway pulls him through. And Miss Darby, especially in the horse-trading scenes, is a wonder. You may even laugh aloud when she observes that geldings, in her experience, are not a good buy if you mean to breed them. And as for Wayne, I believe he can say almost anything and make it sound convincing. (In Otto Preminger’s “In Harm’s Way” he had to say: “I mean to get into harm’s way,” and he even made that convincing.)

Wayne, in fact, towers over this special movie. He is not playing the same Western role he always plays. Instead, he can play Rooster because of all the Western roles he has played. He brings an ease and authority to the character. He never reaches. He never falters. It’s all there, a quiet confidence that grows out of 40 years of acting. God loves the old pros.